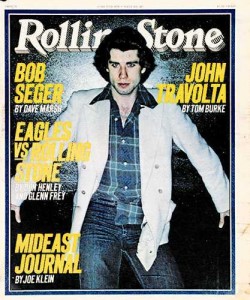

Rolling Stone #267 : Irving Azoff

Cameron, who’s over six feet tall but still a fun-loving kid at heart, went to watch five-foot-three Azoff demonstrate why he’s the roaring lion of rock managers. He discovered that Azoff really likes terrorizing an entire industry. “He’s still short, though,” Cameron reported. How short? “He’s so short he has to roll down his socks to take a s***. He’s so short he – .” Get outta here. Shut up.

A day with Irving Azoff begins and ends on The Phone. Sitting in the platinum-record-lined Los Angeles offices at Front Line management in the morning, an inconspicuous listener can watch Rock’s most influential megamanager do verbal gymnastics that rival any of his acts.

In the time of anybody else’s coffee break, he has a) informed Boz Scaggs his tax-shelter oil wells struck black gold, b) bought a new house for Dan Fogelberg, c) booked part of an Eagles summer tour and d) assured three major record-company presidents they had the inside track on Steely Dan.

“Sure I lie,” yelps the curly headed, five-foot-three Azoff as if it’s also so much mischief. “But it’s more like . . . tinting. I’ve inherited a lot of dummies’ deals. When that happens, you gotta make it right. It’s all just negotiating theatrics.”

They call him Big Shorty, the man who rules the careers of the Eagles, Dan Fogelberg, Steely Dan, Jimmy Buffett, JD Souther and Boz Scaggs. Just thirty, he is the enfant terrible of the music business. To get his clients top dollar, he’ll rip up a contract, yell, scream, terrorize, stomp, pound and destroy inanimate objects . . . gleefully. He is the American Dream taken by the balls. Many of his clients will spend their off-hours watching him “kill” on the phone.

After Azoff has moved around some $20 million of record and concert business, he throws a tweed jacket over his tennis shirt and cruises to MCA/Universal Studios in a borrowed BMW (he owns a Bentley) to show the high-ranking studio intelligentsia twenty minutes of his first executive-produced film venture, FM.

Visiting the Universal office of his friend, Vice President Verna Fields, Azoff first scans a stray release schedule and, while she is on the phone, cradles the Oscar she won for editing Jaws. “Look at this,” he says with the same wonder with which someone else might finger a gold or platinum album (of which Azoff has some seventy-five from twenty different countries). “Feel how heavy it is.” The Oscar slips from his hands and clangs against a glass display case. “Let’s get out of here,” he whispers.

The FM clip he has brought for Universal’s three-piece-suit contingent is an impressive teaser. It blasts through some clever ad-libbing from costar Martin Mull, a romantic encounter in the Q-Sky Studios and some lively Linda Ronstadt and Jimmy Buffett concert sequences. When the lights in the screening room come up, these execs can taste the youth culture revenue.

“Were sitting on a powder keg, Irving,” booms one vice-president.

“Monster, monster, monster,” another clucks. A mischievous gleam begins to take over Azoff’s cherubic face as he listens to the kudos. A moment later, he jumps to his feet. “Well,” he announces, “I’m writing you a check for $5 million and I’m taking the film with me. I can sell it to any other studio in town for ten.”

There is a ghastly silence as what’s-goin-on-here looks fills the room.

“That’s right,” Azoff continues, a little louder. “I just looked at your summer release schedule – you know, the one I’m not supposed to see. I see Stigwood, I see Spielberg . . . where am I? Nowhere. Not heavy enough for Universal, that’s where. I want a May released on this film, and it looks like I’m going somewhere else to get it.”

Within an hour the impossible has, naturally, been achieved, and Irving is back at his Front Line offices across town with his May release. But the first flush of cinematic successes has left him distracted and uncharacteristically silent. “I don’t know about that movie,” blurts Azoff. “Something’s wrong. I tell the studio it’s not authentic, they say, ‘Hey, this is movieland, nothing’s authentic.’ “I’m handcuffed.” Azoff begins to get that look about him again. He jumps up.

“Know what?” He starts yelling to himself now. “I’m 30 years old. I don’t need this shit. I’m gonna get married!”

What wedding present do you get for the guy who’s already taken everything he wanted?” Glenn Frey, guitarist/composer and mainstay of the Eagles, Azoff’s biggest clients, sits in his Coldwater Canyon home several days later and contemplates his managers two newest-by-now-official surprises. Not only has Irving set the marriage date with Rochelle Cumsky, his girlfriend of two years, but he has ordered his name taken off FM. He will still keep his percentage. “You know,” says Frey, “the man bears striking similarities to a Jewish Dennis the Menace.”

“He’s Napoleon with a heart,” says Eagle singer/writer/drummer Don Henley, perhaps Azoff’s closest friend. “But I’m always awed because he’s screaming at some guy twice his size and never gets his face crushed for it. I think it helps that people are shocked at this short, deceptively cute-looking guy who goes to the top floor of a building and just explodes on some guy for his incompetence.”

Along the way Azoff has ushered the rock music business past its last Sixties vestiges of brotherly naiveté. His philosophy, he agrees, is to get as much as possible, “but with the right creative decision. We don’t rip anybody off . . . it’s just comes down to hard, cold business. I was very fortunate, as were my clients, that the time we all hit, the business quadrupled. A gold album don’t mean shit now. If you handle an Eagles, their road crew and families, you become responsible for fifty-five people and you’re running a $15-million business. You gotta know how to handle the money. You don’t handle it right and the government’ll come take it all away from you.”

Azoff was a plump seventeen-year-old in Danville, Illinois, headed for a career in medicine when he discovered big-time rock & roll. After watching the Yardbirds play in Indiana Beach, Indiana, there was, he says, no looking back. He had already begun by hustling gigs for the hottest band in his high school, the Shades of Blue, and even offered his garage as their rehearsal room. By sixteen, he was jousting with local unions over other bands. “What can I do?” he asks. “I couldn’t play an instrument.”

After high school, a club owner/friend named Peter Pelafos, who ran a small chain of college nightclubs around the Midwest, let Irving try booking his acts. That was all Azoff needed. He was soon, to the amazement of the nearby Chicago club owners, running the affairs of eighty-six artists (like the Buckinghams and the Cyan’ Shaymes) and promoting them across five states. Suddenly, a group could make or break them whether Azoff put them on his circuit.

“I used to sit and read my ROLLING STONE about David Geffen and Bill Graham, and to me, they were gods.”

It was at Azoff’s hottest spot, the Majestic Hills, a former boat warehouse in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, that Azoff first met James Gang guitarist Joe Walsh, who was later to join the Eagles. The 5000-seat Majestic Hills was unique for two reasons: there was a tree growing from the center of the stage, and Lake Geneva was just twenty minutes outside Chicago. Recalls Irving: “I told Walsh, ‘You know Pete Townshend was here and jumped off that tree. The guy was fuckin’ crazy.’ Middle of the set that night, Walsh got up in the tree, jumped off, fell down and nearly broke his fuckin’ leg. He comes limping over to me afterward and says, ‘Anything Pete Townshend can do, I can do.’ It was wonderful.” They did not forget each other.

We are now at Azoff’s guesthouse, an appendage of the notoriously-spacious canyon home in which he lives. He is off one of his six phone lines three minutes before his fingers start to absent-mindedly punch numbers as he speaks. When his private line buzzes a moment later, he cannot resist snapping it up.

He talks in little bursts, his voice, as always, sounding like that of a puberty-ravaged Henry Aldrich: “Yeah . . . well choke ’em . . . no way . . . there’s no record company in the world that takes five weeks to release a soundtrack . . . I’ll call some of those nonbrains . . . ” Azoff slams down the phone and addresses the tape recorder. “Excuse me,” he says politely, “but every time I think of FM, I gotta piss.”

The sleepy community around affluent Lake Geneva, it seems, didn’t appreciate Azoff’s intrusion with big-time rock & roll, and one night, with REO Speedwagon headlining, 400 cops, national guardsmen and state troopers burst into the Majestic Hills with gas masks and rifles. They searched people, arresting thirty-five.

The next morning young Azoff found himself in front of the district attorney and sheriff. They offered Azoff a deal: don’t reopen the club next weekend and we won’t arrest you. “I said, ‘Absolutely, man, we’re closed.’ “I got across the Wisconsin state line, picked up the telephone, called WLS and had them put on the news that we would be open next weekend, as usual . . . with Black Sabbath, Jethro Tull and Mountain on three consecutive nights.

And?

Irving chirps his answer: “They enjoined me and I moved to California.”

Azoff moved his one-man agent/manager business to Los Angeles, sharing an apartment with “the one artist, out of all those acts, that I really believed in,” Dan Fogelberg, a young singer/songwriter from Champagne, Illinois. While Azoff worked for the Heller-Fischel Agency, making his name around town, Fogelberg went to work preparing the album that they hoped would “make us both rich and famous.” (It didn’t, but Fogelberg’s second LP went gold.)

The saga is interrupted by the momentous arrival of Front Line press officer and “vice-president-in-charge-of-whatever-Irving-tells-me-to-do, ” Larry Solters. Solters has brought the first pressing of the finished FM soundtrack album cover. It is soon obvious that Azoff, even without the credit/blame of his name appearing on the film or album, has retained a certain vested interest. “I will promote this record,” he says, “because it is a great record. What I’ve done is make my first album in the movie business.” Cursing the individuals involved in editing of the movie which, to quote Martin Mull, “looks like it was cut with a blowtorch,” Azoff scans the package carefully. He immediately spots errors. “They spelled [Donald] Fagen’s name F-A-G-A-N.”

The fingers that have been playing about the phone again have already punched out the number to MCA/Universal. One of the album’s coordinators at MCA and a friend of Azoff’s, is away from his office, so Irving begins to address the heavens.

“Who approved this stuff? This is not what I approved. MCA’s got big problems. Donald F-A-G-E-N is the only one left who hasn’t signed the release yet.” He shouts to Solters, who is already on another line: “We may have a lawsuit here. Call Pam at the office and tell her . . . ”

“Pam quit, Irving,” says Solters.

“No notice? What?”

“She gave notice,” Solters explains. “I tried to hold on to her, offered her money and everything. She wanted to get out of the business. What could I say? Good move?”

“So who’s left in the office . . . just Nina?” Azoff instantly tracks down his office manager at another appointment. “I’m trying not to explode,” he informs the individual. “I’ve got Solters up here discussing the 47,000 fuck-ups with FM . . . Pam quit, you didn’t tell me she’s leaving . . . ”

The office manager says what must be the wrong thing. Irving suddenly throws up his hands and takes his voice to another dimension of hysteria. It is truly amazing to hear him scream: “I DON’T KNOW . . . I DON’T KNOW . . . BUT I SHOULDN’T HAVE TO FUCKING WORRY ABOUT IT . . . SO OBVIOUSLY IF YOU WANT ME TO HIRE AND FIRE PEOPLE . . . I’LL HIRE AND FIRE PEOPLE. SPRING FUCKING HOUSECLEANING! NOBODY’S SAFE. IT’S GONNA BE JUST ME IN THE GUESTHOUSE WITH TWO SECRETARIES!! JUST THOUGHT I’D LET YOU KNOW.”

He jackhammers the receiver and, purged of his demons, begins to do a little jig.

“Going strong today, Irving,” Solter observes impassively. “Just one question. Am I gonna be one of the secretaries left?”

“Yeah,” says Irving.

“Good,” says Solters. “Because the man at MCA is on the phone and I think he just slashed his wrists.”

“I was totally down and out, living in Colorado. Lost. Couldn’t get any gigs . . . made a solo album, and the IRS was auditing me three years running. My manager didn’t even care,” says Joe Walsh. After the James Gang and hits like “Walk Away” “Funk No. 49,” the guitarist had his nadir playing the Whiskey A Go Go in Hollywood for virtually no money.

“Out of nowhere, Irving came up, saying he believed in me. He was a booking agent and wanted to at least keep me working until I could straighten my career out. He never asked me to manage him. I was overwhelmed. He was the only guy I’d talked to who had answers. I just gave him everything, completely trusted him and said, ‘Help.'”

Azoff put Walsh together with the lawyer, Lee Phillips, and the two set out to untangle the numerous entanglements of Walsh’s plummeting career. Walsh eventually asked Azoff to manage him. “He said, ‘Shit, I’m flattered. That means I don’t have to be an agent anymore.’ We made a pact they’d never take us alive.”

Azoff did not have the collateral to open his own management office. At suggestion of Phillips, also David Geffen’s lawyer, Azoff went to work out of Geffen’s and Elliott Roberts’ GR Management company, bringing with him Fogelberg and Walsh.

“I had been petrified of working with David,” claims Azoff. But Geffen, who was also president of Asylum Records at the time, had just merged with Elektra records and was heading for a new office. “It ended up just me and Elliott running the office,” says Azoff. “I was a nervous wreck. We had everybody: Crosby-Nash, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, America, the Eagles, J.D. Souther . . . David had signed Dylan, so we were working on a Band tour as a favor too. Elliot and I were going fucking crazy . . . It was way understaffed.”

Azoff was eventually dispatched to Kansas City to chaperone the Eagles along some of their ’73 Desperado tour. He found a band that was suspicious, broke and aimlessly zigzagging across the country to half-filled houses. Frey and Henley had already held secret meetings with an assistant at GR Management who had confirmed their suspicions of being “badly neglected.”

“The first night we met Irving,” remembers Frey, “Henley and I and him got in a room together. There was something about it. We started telling Irving our problems with the band, our producer, how we wanted our records not to be so clean and glassy and how we were getting the royal fuckin’ screw job.

“He told us he had come in with Walsh and Fogelberg and didn’t know himself. It was perfect from the start. Here was a guy our own age, going through exactly the same thing, catching his rising star the same time we were. We decided that night that Irving would manage us.”

The Eagles began to make public their unhappiness with the Geffen-Asylum connection as Geffen and Roberts were deciding to pare the roster down to a more manageable Neil Young and Joni Mitchell. “Geffen told the Eagles they could leave,” claims Azoff, “but I don’t think they anticipated I would take ’em. They were pissed.”

“When were we convinced we’d made the right move? Pretty quick, admits Don Henley, six platinum albums later. “Might have been the Bahamas Incident.”

“The Bahamas Incident,” Glenn Frey agrees. There is a reverential silence as Frey silently goes over to the stereo system in the rented L.A. home where he and Henley – “my managers” as Irving calls them – are writing the songs for the next Eagles album. Frey puts on Ralph MacDonald’s eighteen-minute drum epic, “The Path,” and begins to tell the story.

“We have been with Irving six months,” Frey starts. “The Eagles were in the middle of a [1974] tour. We had two days off and didn’t want to stay in New York. We were into big gambling thing – cards all the time – so we decided to go to the Bahamas and gamble for our two days off. Henley, myself, Irving, a pilot and a girlfriend with Don take off for the Bahamas.”

Henley: “We go through this whole thing about not taking anything over. ‘Okay, now, everybody’s got to go in clean . . . . ‘ Everybody goes, ‘Yeah . . . We know . . . I’m not taking anything over, no.’ ‘Me neither.'”

“Turns out,” continues Frey, “everybody except Don and his girlfriend had some kind of dope on him. Irving, on the plane over, took twenty Valiums and put them into a sugar package and stuffed them in his shoe. I put half an ounce of marijuana and my boot. We proceeded to go off to the Bahamas, you know, figuring everything would be okay and there was no way we were gonna get caught for that little bit.

“Well . . . the first person to present her bags [at customs] was Don’s girlfriend. They started looking through her purse and found a pack of cigarette papers. The head customs man, a big guy, starts asking questions. This guy is out to bust us.

“Before we knew it, all six of us were being taken off to be searched.” Somehow, everyone else managed to dump their stuff, leaving me and Henley and Irving,” says Frey. “The two young assistants who are searching everybody physically in the next room say, ‘Who’s next?’ Irving says, ‘I am.’ We look at each other, knowing we can’t reach in our boots. He’s ready to go to jail, right now. Irving goes into the search room and . . . I know he’s getting busted. I’m just waiting for the whole sorry thing to happen . . . waiting for me to be called.

“Irving comes out of the search room five minutes later gives me a wink. Then he walks out scot-free. Now I don’t know what the fuck is happening. Next thing the two assistants are walking toward the door, saying ‘Well, that’s it, chief.’ They search Don, skip me and let us all go.

Frey smiles proudly. “Here is what happened. Irving, when he got into the search room, reached right into his boot, pulled out the Valiums and said, ‘This is what you’re looking for from me . . . I don’t have any prescription bottle with me, but my father is a pharmacist.’ Then he pulls out a fistful of twenties, our gambling money [$5000].

“They wouldn’t take his money. So Irving, on a moral level, did the great sales pitch of all time. He said, ‘Now you guys look like young guys. There’s a kid out there with a blue shirt on who has gold records all over his wall; he’s a rock star. He’s just got a couple of joints with him. If you bust him here, he can’t play in the U.K., Australia, Japan. He brings such enjoyment to people and you’re gonna end his career.”

“One assistant says, ‘If we find the dope on him, we gotta show it to the chief.’

“The other says, ‘No, we don’t’, takes the Valium and gives them back to Irving,. ‘We’ll try to skip him,’ he says.

“That was a real-life panic situation. That required more fortitude than doing a concert deal with Bill Graham or something. He definitely had to dig down deep for that one. He saved our ass from winding up with an international drug charge.”

“Hell,” concludes Don Henley, “somebody’s gotta fly this thing.”

Front Line management was in the black from the start. Joe Walsh released The Smoker You Drink, The Player You Get and, as “Rocky Mountain Way” took off, he became a bigger attraction than the James Gang at their peak. Fogelberg released the gold LP Souvenirs, Walsh’s first production. And Azoff introduced the Eagles to a new producer, Bills Szymczyk, and their pivotal On The Border album (featuring “The Best of My Love” ) was finished. “We were,” says Big Shorty, “off to giant start.”

When David Geffen left the Elektra/Asylum post for Warner Brothers films, Azoff was the new empire-builder in town. He hired in-house everything on a fee basis, voraciously eliminating the needless percentages of business management (five percent), a booking agent (ten percent), publicity and more. He renegotiated his contracts every year. His acts toured sparingly, but for maximum profit. The Eagles, Walsh and Fogelberg – like Front Line – began to operate like a well oiled machine. “When you start splitting everything up six or more ways,” says Frey, “you start looking for the extra dollar. And searching for the extra dollar, we’ve found fortunes. Of course, we want to make more money and know where it goes. Why be naive about it? Why die like Stephen Foster, in the Bowery, slitting his wrists, penniless after writing all those wonderful standards.”

For some time Azoff kept his energies just to the Eagles, Fogelberg and Walsh. Then Boz Scaggs, needing a manager, came in for an appointment. Scaggs had heard of Irving and, after managing himself for a few years (“a lot remained undone”), Columbia records, his label, set up a meeting just before releasing Silk Degrees. “He had grown up and developed entirely within this huge industry,” Scaggs says. “It’s awesome at first how much information he carries. I’m convinced he’s gonna be the guy who gets everybody from the Sixties to the Eighties.”

“Boz has since become a very close friend as well as my client,” Azoff says. “I come under criticism, you know, from the ‘rock manager elite.’ How can your clients also be your social peers? That’s the way it happened. It’s like . . . it’s almost like a rock & roll fraternity.”

And, some might argue, Azoff is just panty-raiding his way through the music business. “The ultimate decision I came to was that the whole key to real power in the management business is not to pat yourself on the back and say, ‘I did it.’ I have tried to break a new act every year . . . ”

With the latest additions to Azoff’s operation, Jimmy Buffett and Steely Dan, he has done just that. Both have turned the corner on platinum status since signing with him.

“Why sign with him?” asks Donald Fagen. “He needed a new hobby, why not?”

In fact, Steely Dan and Buffet both had career entanglements. And legal entanglements – contracts – are Azoff’s forte. (He has even taught artists like Bob Seger and Glenda Griffith to “play ball” free of charge.) What enables a man to rip up a contract? “Our wonderful court system takes three or four years to try anything. So while you’re trying to dispute, an act dies and a record company loses multi-multiprofits. So they’ve forced to arbitrate, and it comes down to the old music business tactic of the guy that yells loudest is right. It’s not my fault I have to yell loudest.”

Back in his Front Line office and working late, Azoff is asked about his detractors, of which there are more than a few (in fact, his office wall was once lined with hate mail). The people that don’t yell loudest. The ones that refuse to be quoted for this article. The ones that swear they’ll get him on his way down.

“What way down?” Irving asks innocently. His fingers begin to play with the phone again, but the intercom that only a few hours ago buzzed with calls from Richard Dreyfuss, Kenny Stabler, Donald Fagen, Dan Fogelberg, Alan Cranston, Jerry Brown’s office and all the clients who want to hear the victories of the day . . . is silent. For once, it will not take two hours for him to finish a thought . . . .

“People that aren’t close to me would think I kill for sport . . . you gotta kill sometimes.” He becomes impassioned. “When you get the $40,000-a-year promotion man at the record label who leaves at 11:30 for lunch and comes back at three – and doesn’t work Fridays – you know, it’s a salaried gig to those guys. Here you go, you take your record, your artist’s career and your whole family’s future – you put it in the hands of a man who isn’t gonna make one more dollar if the record’s a hit and what you’re doing is crossing an artistic process with a guy that might as well be selling fucking typewriters. I’m not gonna let some fuckhead stand in the way of that record being a success. If the guy ain’t doing his job, he’s gonna hear about it.”

Last January, Azoff won an unprecedented settlement to retrieve the Eagles publishing back from Warner Communications, the enormous conglomerate that owns Warner/Elektra/Asylum records. With typical zeal, he sued them for $10 million (“my scariest adventure in the business”) and hung on, bit and scratched, as one executive put it, and Warner Communications gave up after two years. “They legally owned our songs,” admits Frey, “but it just wasn’t fair. Nobody has that right. Those songs are our birthright and part of our children’s heritage. Besides . . . it also means I don’t have to hear ‘Take It to the Limit’ as a tire commercial. I thank Irving Azoff every night for that.”

Azoff’s harsh baptism in the movie business does not mean that he will not attempt another entry in the near future. “He takes a lot of meetings of film people,” says Henley, “and he doesn’t forget anything. He’s amazing. He does everything from having my drive-way evaluated to seeing if my property doesn’t extend further to calling program directors direct. He does it all himself . . . and still has time to play tennis.

“We owe him a lot. And when we go out on the town there’s always that look in his eye: ‘This is me and . . . these are my boys.'”

Irving Azoff has that same glow as he walks down the aisle of Stephen S. Wise Temple to his marriage. The Eagles, J.D. Souther, Boz Scaggs and a templeful of Azoff’s closest friends and clients look on warmly. Dan Fogelberg, the original Front Line roster, sits at the organ and plays, instrumentally, his own “To the Morning” and later, Frey’s and Henley’s “Desperado.” The rabbi reminds a demure Irving, the same man who ripped apart two hotel rooms in Florida once just to see what was behind the walls, that he now has a “responsibility to world peace and elimination of destruction.” Irving nods respectfully, a rare sight.

“Look,” he would later confide at the wedding reception in his backyard, perhaps trying on humility for size, “maybe you should just strike all that stuff about me yelling . . . And Universal . . . and everything. Here’s the story: I’m thirty, I come from a tightknit Jewish family. I’m crazy. I’ve got all the power and money I could have wanted. I just don’t think you can balance your nervous system at age thirty without a personal life. I don’t have to yell a lot anymore. I haven’t destroyed a hotel room in years. I’ve met the right person and I’m settling down.”

And on that note, Irving Azoff tenderly smashes his mother-in-law in the face with a piece of the wedding cake.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #267 – Cameron Crowe – June 15, 1978