Rolling Stone #161: Jackson Browne

A Child’s Garden of Jackson Browne

It’s a long way Jackson Browne has come – from his whining days at the Paradox in Orange, at the Dom in the Village, and at Troubadour hoots in Hollywood. No longer the high-schooler/songwriter with the unharnessed voice, Jackson has become a shiny, if not perfectly polished performer. With two successful albums – and even a hit single-behind him, he is a recording star. And, most recently, the man with the forever-young face has become a father.

But tonight, backstage at the Berkeley Community Theater, where he has just headlined, he is nervously shifting his weight from foot to foot, surveying the dressing-room cluster of old friends like a bashful birthday boy at his own surprise party. The faces from his past now drinking champagne from plastic cups are the people that have inspired and populated many of his songs.

He doesn’t seem to believe their praises, to be able to absorb the backpats. The midpoint in his first major tour on top of the bill (with Linda Ronstadt as opener), the Berkeley show had been painfully mediocre. Jackson had seemed preoccupied between numbers and let his between-song stories wander pointlessly, spaced ellipses that led to nowhere.

In the end, the music triumphed and the audience forgot the spoken words. But he had tried too hard. Perhaps it was nervousness before his Orange County friends, but probably it was the disconcerting fact that he had suddenly been left in charge of his baby boy, Ethan, then eight weeks old. The baby’s mother, Phyllis (the model, actress and star of the bar-fight/knock-up adventure described in Jackson’s song, “Ready or Not”), had taken ill and flown home to Browne’s Highland Park mini-villa that afternoon. Only later, at a pizza parlor with high-school buddies Steve Noonan and Greg Copeland, and with fellow singers Paul Pena and Pamela Polland, among others, would Jackson finally relax. Saying good-night, he began wandering around in circles, until a circle of friends formed, joined hands and swayed through “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” each old friend taking a turn with a verse.

The next night, an out-of-the-way gig at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo had to be better. In fact, it was brilliant. With Jackson editing his stories down and alternating between guitar and piano, while the band (Doug Haywood on bass and perfect harmony, Larry Zack on drums, and David Lindley on violin, banjo and guitars) sounded superb, adding both depth and electricity to songs that before last spring had relied only on Jackson for instrumentation.

Back in his hotel room after the show, Jackson played with his baby for a moment, pushed aside the debris of past diaper-changing episodes, and fell into an easy chair. Last night was on his mind.

“That was the first time most of those people had been together in the same room in God knows how long,” he said. “I’ll tell you, we used to sing freedom songs by the hundreds. It wasn’t that we were such dedicated civil rights workers; it was just that we wanted to get it on. We’d stay up all night raising hell.

“There’s a distance, a film between us now. Everybody’s essentially the same; it’s just the situations that have changed. I mean, I love those people, but I spend my time differently now. Anyways, those things are always very awkward at first.” Ethan yawned squeakily.

Jackson Browne returned last year to the house in which he was raised from the time he was three to just before he became a teenager. Today the house is all baby and music, in a setting dreamt up and built a half-century ago by his grandfather, Clyde Browne. There is no other house around like this one in Highland Park. But Clyde Browne, a printer who was considered by his disapproving wife to be an eccentric, was bent on recreating a California mission to be his home. He spent 12 years on it, beginning in 1915, called it “Abbey San Encino,” and it would become home to his son, and then to his grandson, Jackson.

And now on the parson’s table in the living room, there is the birth certificate for Ethan Browne, born November 2nd, 1973, at 6:40 AM at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and there are the proud Polaroids – the kind that develop before your eyes – of Jackson and Phyllis taking turns holding the baby.

Boxes of Wipe Dipe are in both the living room and the adjoining bedroom, where the baby’s crib sits at the foot of his parents; tattered-quilt-covered bed. On one shelf, tucked back against a wall, is an unopened box of IT’S A BOY! ROI TAN cigars. Outside, across the patio that serves as the cover of For Everyman, past the well and under the bambooed eaves of one walkway, a voice sings a lullaby in a foreign tone. It is the housekeeper, a woman from San Salvador, and she is in the kitchen, cradling Ethan in her arms while his father is out shopping.

Down along the other side of the patio is the chapel, used by grandfather Browne as a print shop, but equipped with a 14-pipe Angeles organ that takes up the entire end wall. Wrapped around the bases of the four central pipes is a banner declaring: “Golden notes from Leaden Throats.”

Jackson uses the chapel as a rehearsal room, and these days, between tours, he is writing songs into an accounting record book propped up against the grand piano. He’s on about page 105, working on another song of retrospection, of the man looking back at the child: “In my early years I hid my tears and passed my days alone/Adrift on an ocean of loneliness/ My dreams like nets were thrown…”

And at the end of the snake dance of cords from amps and speakers, across from a small platform that serves as a rehearsal stage, is a carrying case, ready for the next tour. It is white stenciled: “JACKSON BROWNE-FRAGILE.”

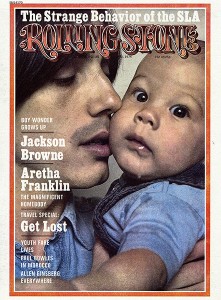

Back from shopping, Jackson picks Ethan up and begins to pose for a photographer. He flips through the Polaroids and finds the one shot he’d like to duplicate: of him holding a broadly smiling Ethan. Back in the bedroom, he works with his free hand, slapping fingers together, and he makes gurgling noises and sings the refrain from “The Cover of Rolling Stone.” Ethan laughs, and Jackson is unknowingly open as his baby: “I love it when he laughs,” he says. “His little voice. His little throat.”

Jackson Browne is 25 years old now. He’s been on the loose at least ten of those years. He hung onto friends older than he, losing them when they died or when he began to get into the business of music. He attracted lovers (or, as one of them put it, “pollinated every virgin in Southern California”) and lost them (or as he put it: “I got my heart crushed about eight times in a row. It would happen every two years or so; I’d forget and fall in love.”).

Those years have gone into maybe 70 songs-his guess-and, since 1966, when he himself began to sing at hoots in Orange County, many of those songs have become standards in the portfolios of dozens of solo-sensitive singers, especially young women who populated hoot nights in Southern California, singing the heartcrush compositions of Jackson Browne.

Jackson became the Boy Wonder of song; he got the right kind of story published in Cheetah magazine in 1968, all about how he and Tim Buckley and Steve Noonan had become the Orange County Three (despite Browne’s denial of any teamwork with Buckley and Noonan beyond one acid-soaked week in Venice beaches and caves). He got a mention in Rolling Stone in 1970 (from David Crosby, who called Jackson “one of the probably ten best songwriters around…he’s got songs that’ll make your hair stand on end, he’s incredible”). But he couldn’t sing too well, and, aside from the hoots and occasional jobs, he stayed off the concert stage.

Now, with voice lessons behind him, he works, happily, in public. And he talks. Onstage, he appears to just stumble into stories. “That isn’t stuff that I figured out before to say. It’s all shit that I said one time or another. And it meant something to me at the time. It’s just like playing an instrument. It’s a lick.”

Clever innocence is one of Jackson Browne’s licks. He is also the Reluctant Star – pure in his own mind, concerned mostly with the music and most impressed with friends like Greg Allman and Ry Cooder, whom he hears as craftsman, first of all. But understanding of the realities of the business. He loves David Lindley as a musician, but he also knows that he can pay Lindley better only if Jackson’s albums do better. He doesn’t like being in the position of hiring a backup band. He’d rather be in a band, like the Allmans or his friends, the Eagles. And yet, he reasons, “I have the best of both worlds. I have a band. And they do my tunes. But I feel a little weird. I’m an employer.”

Schizo, schizo little star. Jackson wants to forget that “Boy Wonder” press about this California creampuff-teen-genius/Nico-lover-after-bragger but he keeps bringing up one particular article throughout our talks, and he grudgingly admits that, yes, maybe he did kind of brag about being Nico’s lover at age 18.

“The details of my life are very boring,” he will say, and yet, as he himself warns, he’ll go on for a half-hour per question; he just needs to be edited. The result is a story that is not at all boring, one that reflects California in the Sixties, how Orange County and the Haight-Ashbury were melded together by acid and music. And how this child of the Sixties, this songwriter for the Seventies, got started.

Jackson was born in Heidelberg, Germany, where his father was a civilian working, after the war, for Stars and Stripes, the Army paper. He was also a Dixieland pianist and, later, a teacher of English and journalism. When Jackson was three, the family moved back to Los Angeles, to Abbey San Encino. But when Jackson was 12, the Brownes, now including younger brother Severin and older sister Berbie, moved to Orange County.

“We were starting to become delinquents, carrying chains. This cop caught us smoking. I was 12. He told us to put ’em out and this guy with me gives him some lip. So it was, ‘Empty out all your pockets.’ A mini-arsenal. And it’s only a block from my house. My father drives by and wants to know what’s going on. Evidently it was his pack of cigarettes I had lifted, but they found all these chains and one or two of his really beautiful straight-edge razors from Germany. So we moved. My sister is a whole ‘nother story – the razor blade and the ratted hair and all that. So they just moved out to Orange County and put us in this real sterile tract community.

“I got into music ’cause I couldn’t get into athletics. I couldn’t get into driving a GTO like some kids had. I just didn’t have any money to dress. I would have done anything to wear a fucking varsity jacket. But I couldn’t hang in there long enough. I ran some track and I did a little wrestling. That’s what the skinny geeky kids do. And I blew it. The thing is, I was getting good at wrestling. And that’s a fair sport. They put you with someone your own size. But football, man…all my friends went out for football and like an asshole, I went out for football. And it was terrible. You’re just fuckin’ beating each other on the head and shoulders all afternoon. I cut practice all the time and they threw me out. They wouldn’t let me go out for wrestling because they caught me cutting football, isn’t that a bitch. No fucking flexibility, so then I was an outlaw, right? A desperado. From then on, music was left.

“This is at 14. By the time I was 15, I was hanging out with Steve Noonan and Greg Copeland; that got me writing, too. Greg Copeland was the poet laureate of the school; Noonan played bluegrass before school in the morning; they’d rip off a bass fiddle from the music department. Everybody always talks about how plastic Orange County is, but it’s not. I mean all those blond-haired surfers who were into flashing a bareass at the old Atchinson, Topeka and Santa Fe are total blues fanatics and mushroom freaks. Silver surfers. I don’t think L.A. was any more a legitimate music scene than Orange County, in the years we’re talking about.”

Jackson did soak in some L.A., though-from his mother, who turned him onto Zappa. “She read about him in the Free Press. She was into L.A. and the Free Press. She also introduced me to KPFK. She’s a teacher, and she was always interested in freaks, kids.” And Jackson watched TV rock, circa 1964.

“I remember watching the Lloyd Thaxton program one night and this pretty chick is singing ‘You Won’t Forget Me.'” Jackson sang a verse. “And it was beautiful. Suddenly he was talking to this chick, Jackie DeShannon, and he said, ‘You wrote that song, didn’t you?’ and she said, ‘Yes,’ and I went, ‘Wow. She made that up?’ I didn’t know where songs came from. I figured people got them from the supermarket or something. I had never thought about that. It really knocked me out.” And of all the Byrds’ folk rock he was hearing, he especially liked “Don’t Doubt Yourself, Babe,” another song by Jackie DeShannon. Jackson decided to try some writing of his own.

He began with love songs. “‘Happy Woman Blues’ was about getting your ass kicked all the time by one chick. Mainly it was dumb shit, it wasn’t so much out of experience as it was imitative.

“Steve and Greg were writing civil rights stuff, ‘The Ballad of Rosette Park”-really powerful. I tried writing some civil rights songs, but it came out real stuffy-sounding. I never was too political or topical.

But Jackson Browne would grow up fast and accumulate experiences that would result in songs that would be recorded and spread by such artists as Tom Rush, Jennifer Warren and Steve Noonan.

“In ’65…I was 16. My hair got real long because it just did. And A Hard Days Night was out. It was magical. Down in Orange County and in San Francisco, people were getting incredible.” And Jackson began to roam, to become part of this “great lysergic…circuit.” Along with his high-school buddies there was Roger, from the mountains near Palm Springs.

“Eventually, finally…the first time I was on acid, Greg Copeland was taking us to the store ’cause Roger and I were prenatal idiots. And this cop…I’m like-I’ll get high if I start to tell you, but it was so funny-I just said [whispers], ‘I wanna be this way all the time!’ And it’s nine o’clock in the morning and I’m screaming, “AAAAAAAARRRRRRGH!’ I’m ecstatic. And I’m pulling out these various combinations of lint out of my pocket, and no two are the same. I had leant this coat to Steve Solbrook to work all summer in and I had it back. It was my favorite coat. I got it back and there was this treasure, and I’m spewing all this shit out. A cop rolls by and I’m screaming. I wasn’t doing anything wrong. I was very happy, walking down the street, and he had to check it out. He put us all in the clink. And Greg, who’s supposed to be looking after us, the only thing he said as we go shuffling into the back of the patrol car is, ‘You mind telling us what you’re doing to us?’

“Now, Roger looks like a fucking Breck ad. He’s got shoulder-length, very beautiful blond hair and a very young sort of pubic reddish beard that only grows on the throat. And very pink skin. He’s like a snail without a shell. And whatever happened, Roger wasn’t gonna betray himself. The cop mumbled something about his beard. And Roger just said, ‘Yeah, do you like it?’ And he wasn’t lipping off. The cop turned around, ready to just get really pissed off ’cause this guy was getting fresh, and he looked at me and then at Roger, who was looking at him with so much sincerity and innocence, and the cop was embarrassed to think this kid was gonna get fresh with him. He didn’t know what to think, and he said, ‘Well, you know, maybe you could trim it or something,’ and Roger said, ‘Oh, no, I couldn’t do that.’

“I think probably a couple months after that, I write ‘These Days.’ That was the most definitive song from that period. It’s a very tired song.” Jackson, in fact, rewrote a line on it, going from “I’ll stop my dreaming/I don’t do that much scheming” to “I’ll keep on moving/Things are bound to be improving” to cut down on the meditative cynicism of the song.

“These Days,” first recorded by Tom Rush in 1968, has only recently been brought back to life, by Ian Matthews, Gregg Allman, and, finally, but Browne himself last year, on For Everyman.

“Over the years, I only felt that song about three or four times,” he said. “I forgot all about it for about three years, and then I did it once, the time I met David Lindley…. Jimmy Fadden [of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band] brought him up to the dressing room at the Troubadour and he wanted to play. I knew him from the Kaleidoscope and I knew he was great, and he brought his fiddle and, suddenly, the song had so much feeling because of the way he was reacting to the words. And the melody. And Jimmie playing harp on it. And then we went onstage and it wasn’t anything like that. Puzzling. Then another time I felt it when I played with David Bromberg and he played such beautiful shit with it. But all the time, it was a completely different song than the one we did [on Everyman. It was folky. And then when I heard Gregg do it, there it was again. There was the song, the feeling.”

“These Days” was written around the time of Jackson’s second acid trip, two months after the first. “It was on acid….Those moments are really blocked out of my mind.” But not completely.

“It was great-the same guy, Roger. Here he is, we’re both on acid at the breakfast table and his father proceeds to get hostile with him because of his appearance. He’s still very Breck-like and rosy and he’s wearing all black. Black Wellington shoes, black stretch Levi’s and black turtleneck, and he’s wearing this big jewel around his neck because he’s got to look the part. Flower child. He’s got to look at everything through it. And I was just about to rub my eggs in my face because I was having a very sexual life-energy trip with my food. I thought: ‘Food-it keeps me alive!’ And I was just about to go ‘GRUARRRGH’ and rub the eggs in my face, but this incredible wave of hostility comes down with me and Roger and something about ‘What kind of son have we raised here?’ And we’re so high, there’s no way of dealing with or talking with him. So I got very sober, very quick, and I calmed down and I finished as much as I could finish and walked outside where the clouds were doing this incredible number. Earl Carroll number. I went out there and I just went, ‘Jeeez.’ Great times.”

Another growing-up-absurd friend of Jackson’s was the inspiration from one of the most often requested songs in concert: “Song for Adam,” the friend who committed suicide.

“He was this friend of Greg Copeland who had this great character. Although he was very salty and sarcastic, by the end of the month hanging out with him, we all really cared about each other. Greg and Adam went to Europe and wound up in Tangier and eventually India. I wanted to go, but I didn’t have the money to do it. Adam was this biology freak, and people were down on him because he once took somebody’s cat apart. This one girl that we knew was, surprisingly, seen with him. Everybody, you know, was already knocked up and had kids at the age of 16…. There were these one or two girls that were keeping their virginity. They were every bit as “in” there with you and all, but they were 18 and they weren’t about to fuck you, that’s all. But this one chick, Adam’s old lady, regarded him with some awe because he got her just like that [snaps finger]. They were living together. ‘Liz is no longer a virgin? Who’s the guy?’ And he was this weirdo who dissected your cat if you weren’t looking. But he was a high person. He was good. Very salty and very secretive. I didn’t know him too good. They weren’t in the same grade, they were two years older. Adam might have been three years older, he was Greg’s friend. When they said, ‘Do you want to come and drive across the county?’…I really admired the guys. I went with them, but I didn’t have the bread to go to Europe. I was just 17. Also, New York was such a…number. I just wanted to get back to California where I knew a few people. When we got to New York, I hung out with Noonan, got a job singing at the Dom.

By the time he got his first gig in New York, Jackson had been hooting for a couple of years. He was even a short-term member of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band in 1967, when he was 17. The band was just getting organized and Jackson stayed several months into the summer for gigs at the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach and the Ice House in Pasadena. “Eventually it got so that I just couldn’t…my heart wasn’t into playing ragtime music all the time. I wanted to play my own songs.

“We all started working professionally around the same time. I was playing at these clubs, at hoots and just hanging out. It was what I did on weekends.”

In Orange County, the main hangout was the Paradox, a small, 200-capacity box that, along with its next-door neighbor, a 7-11 store, accounted for all the night lighting there was in the city of Orange. Regulars included Tim Buckley, Steve Noonan, Hoyt Axton, Ramblin’ J. Elliott, Penny Nichols, Dick Rossmini, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

And this romantic kid, Jackson Browne.

“I remember seeing electric guitars when I was really tiny. I thought a guitar with a wire coming out of it was the dumbest thing I’d ever seen. ‘Cause I loved the whole beneath-the-trellis-with-the-guitar number. Or hunched over a guitar at the beach. That was another beautiful image to me. It was also a hell of a lot warmer than being out in the water. There was always a guitar when we’d go surfing.

Jackson became a regular. “For a while, people from school would come and hear me play. I got so that I was a draw because it was a novelty to go see somebody that you sat next to in school, onstage.”

He became one of the bigger of the skinny geeks on campus – “for the last month or two,” at least, “as a result of playing. ‘Cause mostly in school they knew me as this guy that had got his heart stomped on early in the semester and was sort of out on the bench. I really, literally, spent the entire time – except for the classes – on this bench, just sitting there, staring off. This one chick just ruined me. Goddamn.”

Did Jackson ever think where the crusher might be today?

“I hope that Wayne Seafelt took her and got a van and they became hippies somewhere – took acid and got beautiful.”

One result of the Paradox hoots was Jackson’s first step into recording, and finding a manager, Billy James. But while Jackson had songs like “These Days” and “Shadow Dream Song” already written by the end of senior year, he still wasn’t ready. For one thing, despite the hoot-night workouts, he couldn’t sing well. He remembered one time at Billy and Judy James’ house, where he was staying, and writing:

“I wrote a melody way out of my range, way down low, because I didn’t want to sing out. And you gotta sing something to know if it’s right, if it sings well. And I don’t want Billy and Judy to hear it because she’s cooking dinner and he’s in the other room, and I’m singing way up high and way low, and the whole house gets very quiet. Suddenly the door opens and it’s Judy, saying, ‘Are you all right?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’m all right. I’m writing a song.’ She says, ‘I thought there was someone choking to death in here.’ And she closed the door.”

Jackson Browne’s first recording contract was with Elektra, signed while he was still in high school, in 1966. It was a songwriting contract.

After graduation from Sunny Hills High, Jackson had gone East with his pals Greg and Adam, and stayed with Steve Noonan. He got a job at a Stony Brook concert with Tim Buckley and Noonan and followed Buckley into the Village, where Tim had a job opening for and accompanying Nico, Pop Girl of the Year with the Exploding Plastic Inevitable and the whole velvety underground as it was then laid out by Andy Warhol, who’d lent his name to this one club, the Dom. “Tim just got sick of singing in that environment, so he quit after a week, and I became her accompanist and also did the opening act. I did this for about six weeks and made untold hundreds of dollars and I…just got out of it. Went back to Los Angeles. The next year, they put me on at Stony Brook again, this time opening for Judy Collins. I did a terrible set.

“The most significant thing about the whole New York experience at the Dom is that it was the first time I’d ever made $100 a week in my life. I made $10 a night at the paradox and sometimes I would give it up because I knew it cost them that much to make the fucking cookies that week. I just said, ‘Look, I don’t need the money. I live at home. Thank you for the opportunity.’ But this time I made a bunch of money, and in spite of the fact that I blew a lot of money, I came home, with $500.”

Of course, there were other significances.

“I’ll tell you, I had a gigantic crush on Nico. She was so fucking beautiful. She fucked me around, really…goddamn, man, she was just…and I had seen these 20-foot-high posters of her for the three weeks I’d been in New York and then I went down and saw her-it was even my first time in a bar, I think, ’cause I’d just turned 18-and a week later I got a call, would I like to be her guitar player. I went over and got my brains fucked loose. It was much later, a month later, before I realized that the whole thing was just like this fling. I really cared about her in spite of the fact that I was really disappointed. I mean, I dug her.”

Also in New York, Jackson met Leonard Cohen. “That was real important. He used to come in ’cause he was real infatuated with Nico, and he would sit there and write poems on the front table and just sit there and look at her. He’d write these perfect poems on little pieces of paper. He’d just knock them out in between songs and read them to us and get very dreamy. He was an old-fashioned poet, which was the only kind I knew there was. I was real impressed with him. I was no fixture at all in that scene. I made no impression on it.

“What R. Meltzer said in that article-that I became the object of many lustful old faggots-was not professional. Because I really didn’t know what was going on. I mean, I realized it later, just remembering scenes of what people said to me. But it was like candy or something. I knew what a fag was, you understand, and I knew that when this outrageous transvestite came up and said he was Nico’s little sister… ‘I’m Renee Ricard and I make movies with Andy’…I knew what it was. It scared me. I kept my distance.

“But these other people, these more menacing people…Lou Reed, who always had this incredible menacing scowl on his face, wouldn’t say more than one or two syllables because that’s how Andy was. The conversations went like this” -Jackson drooped his lids and began a series of soft moans. Later, at a rehearsal session for Nico’s Chelsea Girl album (Nico would record “These Days”), Jackson met Lou, who told him about the love-in that had taken place in New York that day, the same day of the be-in in San Francisco.

“Lou Reed is a sweetheart underneath. We got to rapping and he turned out to be this great person. And the way he described it, you realized there was a place for all that inside of him. He loved seeing Central Park full of people all just…high and loving each other. I mean, you don’t think about that when you think of all those Warhol people.” In New York, Jackson said, he wrote “The Birds of St. Marks.”

“No one’s heard that song. It’s a sad song, very strange.”

When Jackson’s label, Asylum, merged with Elektra records last year, Jackson must’ve felt some irony, since he had first signed with Elektra in the fall of 1966 as a songwriter.

He had met Billy James, then a Columbia Records talent scout, through Pamela Polland, a Bob’s Big Boy waitress-turned-singer (with the group Gentle Soul and then by herself). James, who managed Polland, advised Jackson against participating in an informal hoot album, to be sold at the Paradox. Billy tried to interest Columbia in Jackson, but the company didn’t bite, and when James moved over to Elektra Records as West Coast director, he got Jackson signed in September 1966.

Songs began to find their way onto records: Tom Rush, on Elektra, recorded “Shadow Dream Songs,” on The Circle Game, a 1967 album that also introduced unknown composers named Joni Mitchell and James Taylor.

But the most memorable product of that period was something Jackson dearly wants to forget: “Elektra made dubs and stuff,” he said. “But they did a real foolish thing. They made up a dub of 30 songs and just passed them out like they were fucking periodicals. I sang them all in four hours and they were really bad. I just couldn’t sing. They’re still floating around somewhere. I personally have maimed 40 of them, but there were a hundred printed. They’re ugly.”

Within a year, James left Elektra, and the label released Jackson Browne. The next year – 1968 – Elektra would get interested again.

Meantime, Jackson was on the road. He did a concert in a town near Minneapolis that was put together by David Zimmerman, Bob Dylan’s brother, and he visited David’s apartment, “very ordinary except for this one Hieronymus Bosch over the fireplace,” a gift from Bob. From there he went to New York, scored the Stony Brook job with Judy Collins and returned to L.A., where he nymphed away the summer of ’68 in Laurel Canyon.

“These beautiful chicks from Peter Tork’s house, they kept coming over with these big bowls of fruit and dope and shit. They’d fuck us in the pool. We’d wake up and see this beautiful 16-year-old flower child who only knew how to say ‘fave rave,’ with a bowl of fruit, get you incredibly high and then take you downstairs and go swimming.” Other visitors Jackson remembered at musical jams around the house were David Crosby, whom he was meeting for the first time, and Stephen Stills. They were putting together a trio with Graham Nash.

“We go this idea that we could have all these people come jam with us and we could be like…right on the ground floor of a great repertory company.”

Funny. Someone at Elektra Records was thinking the same thing. The idea was known as the Elektra Music Ranch. Born August 1968, died March 1969, rest in peace.

This, one writer once close to Elektra explained, “was just an experiment. Elektra once tried to start a label run by young people…they had the astrology records…this was another idea: to establish a place for artists to work out, without the pressures to record.”

The idea belonged to Barry Friedman, producer at Elektra and co-founder of another innovation, a seventeen-man supergroup called Supergroup (later renamed Rhinoceros)-and Jac Holzman, president of Elektra, approved. These were the days, you see, of Big Pink – of hanging out and letting the music flow out, as if by communal magic.

Friedman found a piece of land in Paxton, California, 150 miles north of Sacramento in the Plumas National Forest, two plane trips and a Jeep ride away from Hollywood. Friedman found an 18-room resort hotel that had done time, successively, as a whorehouse and an alcoholic dry-out camp. He rented it and installed a remote recording unit, with the controls located in what would become his own bedroom.

Patti Faralla, publicist at the time with Elektra, explained further: “There’d been a lot of talk about taking people out of the urban situation, so they could make music without worrying about phones and traffic and meetings. Other companies thought it was an amazing idea. Another reason for the ranch was that Elektra hoped to form the Los Angeles Fantasy Orchestra-your basic house band-to back solo artists on the road. There was no orchestra. They hoped it would evolve from those people.” And who were those people?

“All of the people were very young, experimenting with their lifestyles and their music. That caused some problems. There was a lot of drugs, and there were a lot of people trying to make musical relationships with people they just didn’t know.”

At any rate, for Jackson Browne, it just didn’t work.

“It turned out to be crazy, incredible jive. The record company-and this is the way these corporate things happen-they needed an album to promote the music ranch. A month after we got there, it was: ‘God, you know what it’s cost us to have this thing up here 24 hours a day?’ And we didn’t get away from the cost and pressure of making an album. So there we were, concepting ourselves right out of music. What we wanted was to be a fantasy orchestra, like a repertory company where, say, Crosby would come and sing with us, and we can get this guy to come up for a couple days…. It was that fantasy that everybody’s had at one time or another. A repertory of artists that all help each other.

“Well, that exists. Only they call it Hollywood or Nashville.”

Another problem at Paxton: girls, the lack thereof. “They were all men up there,” said one woman who had firsthand knowledge of the music ranch. “They stopped writing love songs.” As Jackson tells it in concert, three girls were imported up to Paxton, but that caused more problems.

In his San Luis Obispo hotel room, he elaborated. “There was this one chick who was fucking brainless. We had to tell her what a douche was. ‘Janis, would you please tell Connie what a douche bag is? Please hurry, because…it’s getting bad.” You know, she’d fuck like four of us without douching and a week later, man…And I tried to have an old lady up there. I tried to fall in love with this chick.”

After nine months and at least $75,000 down the drain, the ranch was closed down. “It fell apart,” said Jackson. “It should have.” But before it did, “They made us [several musicians who’d been trying solo albums] be a group and we named it after a tombstone in a local cemetery, the Browning Family Plot, and it just said ‘baby,’ an unnamed stillbirth. So we named the group Baby Browning, very unhappily concluding an album no one liked, and I didn’t even like my part in it. So the album was a disaster and they kicked me off Elektra. Next thing I knew, they didn’t want my publishing. I said, ‘What do you mean you don’t want my publishing?’ And they said, ‘We don’t want your publishing if you’re not gonna be on the label.'”

Jackson slumped into a dry spell, surfacing to write the song, “Opening Farewell.” His friend Noonan, who’d been signed wile Jackson was staying with him the first time in New York, joined VISTA.

Back in L.A., Jackson did some hoot nights at the Troubadour – he had auditioned there before, between trips to New York-and would be hired in the fall of 1969 by owner Doug Weston as an opening act for Linda Ronstadt.

But he was entertaining thoughts of giving up trying to get himself on records. The lesson from the music ranch, he said, was that “you had to be serious about what you were doing, and that it took a lot to make a record, and you couldn’t just float into the studio. Maybe Bob Dylan did, from all accounts, and maybe I had to cope with the fact that I wasn’t Bob Dylan. And I suddenly realized that I wasn’t gonna get to be Bob Dylan.”

A humble Billy James explains Jackson’s split from him: “I wasn’t able to move him as fast as he was ready to move. I don’t do deals all that well.”

David Geffen does. And through the Crosby, Stills and Nash vine, Jackson had heard of Geffen. He made up a demo, with Glenn Frey of the Eagles and J.D. Souther (now working with Richie Furay and Chris Hillman in a new group) behind him. “I went to Colorado. From there I was gonna go to New Mexico and check out the communes. You can make bricks or something. There’s all kinds of things to do, ’cause it was getting really depressing here. And I came back; it turned out he had been trying to get a hold of me.

“Geffen is this compulsive-not now-but at the time he was just this person who gets up in the morning and wheels and deals and is always on the phone and by nightfall he’s like, ‘Oooooooh. I can’t stand this anymore. I hate it.’ Anyway, six months after the Troubadour, I got with Geffen. I thought he might be able to find me a manager or something and I figured that if he encouraged me, then I would do it, and if he didn’t, then I wouldn’t. I didn’t want to go the route of some of those people who’d given me offers, and I knew better than to hang out in the Troubadour.” Geffen told Jackson to relax. Meantime, Geffen formed Asylum Records, and Jackson found a producer: Richard Orshoff, who’d engineered for Johnny Rivers. And he took voice instruction.

“I don’t want to put down the way I sing…I’m not gonna spoil it for anybody who thinks I’m good. I know when I’m singing well, but I haven’t sung well on record yet. I got a ways to go. ”

The first album was finished in October 1971 and held off until January, away from the Christmas-rushed market. Met by critical acclaim and boosted further by the hit single, “Doctor My Eyes,” Jackson got scared again, and his next album would be a year and a half in coming. He had become self-conscious.

“You get the impression that you know what it is that they liked about it, and you try to do that again. You just fall into a bunch of pitfalls and it takes a long time to get yourself out of them. I think my foremost problem was that it got very important to write heavy songs. I mean, I never thought they were heavy when I wrote them, but gradually I got the impression they were by the way people related to them. That’s a bad connection-I’m taking someone else’s word for them. That’s what fame does. It’s a crusher. And that makes me respect people like Gregg and Dicky Betts and their band all that much more. And I respect Elton John because he’s kept going, because he thinks it’s a joke. I admire him for being a pop star. I don’t want to do that, but he does what he does, and then there’s who he is. He just wants to jump over the piano in his neon hot pants. No pretense. ‘They want me to be a pop star? OK, I’ll do that. OK.’ Dylan did that, too. ‘You want a mysterioso whatever, I’ll give him to you.'”

These days, Jackson is bolstered by friends he’s had since the pre-Asylum days, friends who have joined him on the Eagles. He met Glenn Frey (who would add the Winslow, Arizona lyrics to “Take it Easy”) and John David Souther five years ago at a free-clinic benefit in Long Beach. He had seen Frey and Souther perform before, and he wanted them to try this new song of his, “Jamaica Say You Will.” “We were floored,” said Frey. They ended up sharing what Souther called “this adobe matchbox that was already halfway rolled down the hiss,” in the Echo Park sector of Los Angeles.

“There’s no wasted words or filler in his tunes,” said Frey. “Fuck, that kid’s a monster. Jackson’s trip is multidimensional. It’s there musically and lyrically. It makes it a little harder to gain commercial acceptance, but when you do get it, it’s longer lasting. To get right down to it, I’m in awe of him. I’ve seen audiences go through changes during ‘Song For Adam’ that were unbelievable.”

“The first thing we ever tried writing together,” said Souther, “was the stuff that was on our Desperado album. Ned Doheny [another Asylum artist-he’d been part of the Elektra Music Ranch] laid a book about gunfighters on us. It had a chapter in it about the Doolin-Dalton gang. We started talking about it, ranting and raving through the night about the role of outlaw and using that as a metaphor.

“We kicked the idea of all of us being in one group around a lot,” said Souther. “We always refer to each other as the White Temptations. It should be a lot of fun if we ever found the time.”

And there is David Lindley, the instrumental showman of Jackson’s band, called “The Lindley Brothers” because he handles so many instruments: guitar, slide, steel, Hawaiian steel, banjo and violin. Jackson first saw him at a club in Redondo Beach.

“I had never met him there, though,” said Lindley, “and for a good reason. He was underage and the management would scratch a hole in the painted-over windows so that Jackson could watch. He looked like he was about 12 years old. He still looks the same now. I have no doubt Jackson will look that way forever.”

And there is David Geffen. Although Jackson got new management shortly after Geffen became chairman of the merged Elektra/Asylum, he says he’s close to the former agent/manger. “He’s done it for me. All I have to do is keep making records and whatever my slice of the pie is, I’m gonna get. He’s already broken me.”

But here’s the bottom line: Jackson, like some of his songs, goes down apocalyptic: “I think the whole fucking thing is coming down. I think it’s all over. There are hundreds of people in the woods of Vancouver and Oregon and New Mexico who make music and entertain themselves but happen to do something else for a living. As David Lindley has been known to say, ‘Plastic begets plastic.’

“When do I think it’s all gonna come down? Seventies, Eighties, Nineties, it doesn’t matter. The way things are in this world, the fact that people live in square rooms and they go to bars and shit…you know, I used to think it was so lame to go to bars, but now I go to bars. On the other hand, the moment is everything. I can’t deny that I’m from Southern California and I dig going to get a beer, I wanna get high, I wanna enjoy it. I don’t want to pretend to be a spaceman. Fuck that shit. I’m just what I am and that’s however good it is.”

Throughout the interview, Jackson Browne has kept an eye, an ear out for Ethan. When it seems too clammy, he turns down the heater. Now he’s talking about being a father: “I wanted a baby ’cause I wanted to be a baby. I play with him all the time; there’s something pure about it. Look at all those expressions he’s got. He’s a real kick in the ass.”

Baby as toy; baby as mirror. Has Jackson grown up and become a father, or is he still as childish as he looks? In “Ready or Not,” the story of how he came to be settled down with one woman-and even made the gesture of Commitment by buying her a washing machine-he asks for advice: “Take a look in my eyes and tell me, brother, do I look like I’m ready?”

The final question: Are you ready?

Jackson let go with a sure, let’s-go smile. “Yeah, I’m ready,” he said.

Jackson Browne has just one more story: the first time he ever met Bob Dylan, at the Roxy in Hollywood last year, where Jackson was performing. During a break, someone, he remembers, invited him to sit down. “And I’m talking to this guy. Then somebody comes from behind and says, ‘This is Bob Dylan,’ and I turned around and he suddenly looked like a monolith. He looked like Easter Island. He’s wearing a fucking fur cap, he’s got his shades on, gloves and a coat. I just looked at him, said ‘Hi,’ and he gave me this sort of imperceptible nod of the head, and I thought, ‘Jesus Christ, excuse me.’ And I split. I didn’t know how to deal with it. There it was-that mouth, that jaw, those eyes, that inscrutable presence.

“It scared me to death. I went next door and got a drink.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #161 – Cameron Crowe – May 23, 1974