Singles – Rolling Stone

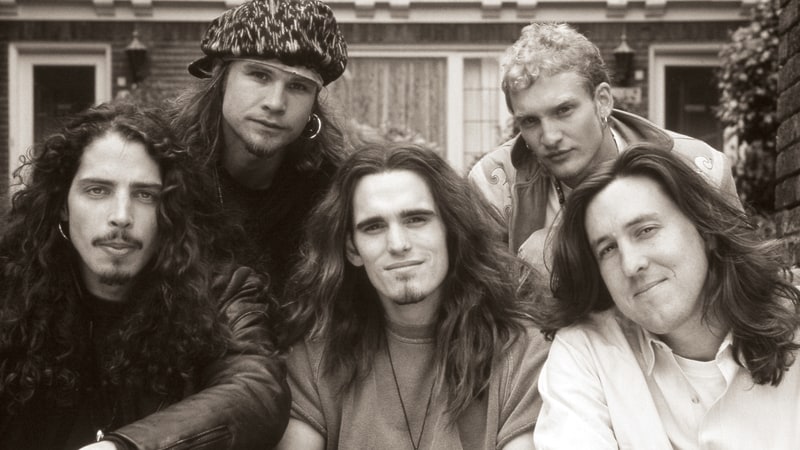

From Left: Chris Cornell, Jeff Ament, Matt Dillon, Layne Staley and Cameron Crowe on set of ‘Singles.’ Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Cameron Crowe on the ‘Singles’ Soundtrack, Chris Cornell

Director looks back on the surreal experience of documenting a music scene on the brink of international fame

This interview was conducted last week, before news of Chris Cornell‘s death on May 17th.

In 1986, Cameron Crowe, in love with a Pacific Northwest girl, and frustrated with the craven scene in L.A. (“hair bands … guys who lived off their girlfriends”) moved to Seattle to make a fresh start. That girl was Nancy Wilson of hard-rocking sister act Heart, so Crowe was soon immersed in the city’s scrappy music scene, frequenting the clubs and getting to know the young music geeks who, often laboring in coffee shops, “worked a nine to five and then played music all night.” Crowe fell in love with the sounds and the ethos, and the idea for Singles, which he saw as a love letter to Seattle akin to Woody Allen’s Manhattan or Spike Lee’s many paeans to Brooklyn, was born.

In many ways, the film’s story is in service to the music. Singles not only featured live performances by Alice in Chains and Soundgarden, but employed a newly drafted Eddie Vedder – just called up to the majors of Pearl Jam from California himself – as well as Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard in acting roles as members of Citizen Dick, the fictional band fronted by Matt Dillon’s lead character, Cliff Poncier. “The first time the cast all got together was at the Off Ramp, a club just off the main freeway in downtown Seattle,” Crowe recalls. “It was the second time Pearl Jam played in public with their new lead singer – Eddie from San Diego. Eddie had read the script, and wrote a new song for the movie, about relationships, called ‘State of Love and Trust.’ It became the soul of the movie in many ways.”

Warner Bros. held the film at bay, unsure what to do with it, for almost nine months, until the explosive success of Nirvana’s Nevermind put all things Seattle on the map. Suddenly the Singles soundtrack, packed to the gills with choice material by almost every other significant act on the scene, was rushed to release on June 30th, 1992, almost three months before the film itself saw light. On Friday, just short of 25 years later, the soundtrack will be reissued with an 18-track bonus disc of demos, live recordings and alternate takes. Crowe talked to Rolling Stone about putting together his ultimate mixtape.

What was your initial concept for the soundtrack, and how did that evolve over time?

Well, so much of the enthusiasm came from meeting and falling in love with a Seattle, Pacific Northwestern native. And when I started going up to Seattle, and ultimately got married in Seattle, part of the whole kind of wonderful feeling of love and community that was so different from L.A. to me was there was this great radio station called KCMU. It was kind of the college station, and it was way to the left of the dial. They played a lot of what would later be called the “Seattle sound,” but they mixed it in with all kinds of stuff, like old blues. What in L.A. would have been called “cheesy R&B” was mixed in with Blood Circus or Mudhoney, and I just thought it was the greatest programming ever. Or somebody would tape Kurt Cobain half asleep having a phone conversation and they’d put that on the air. So I fell in love with the whole mix of genres, and I thought, “If I get to make a movie up here, it’s going to sound like this.”

Right, the soundtrack is not just about Nineties Seattle. You have a Jimi Hendrix tune, “May This Be Love,” and he’s a Seattle native, so you’re dipping back into history a bit.

So much of it came from wanting to do a mix of Jimi Hendrix or Muddy Waters or Junior Wells, along with Mother Love Bone. We’d started to do a little bit of that in Say Anything, the movie before Singles, which was also partially shot in Seattle, and Mother Love Bone’s “Chloe Dancer” is in Say Anything. So it was kind of like I was starting to be able to use some of this music that felt like it was only for those people that lived up there, and I was lucky to have gotten a taste of it. And Ann and Nancy Wilson are big music geeks and they were always surrounded by local musicians, and Kelly Curtis who was their publicist was managing Mother Love Bone, so I was immediately getting thrust into a community of great music and great people.

What came first, the music or the story?

They’re intertwined for me: The music and the city and the people are all kind of beautifully twisted roots around each other. But the music was always there. I used to make cassettes of KCMU so that when I had to come down to L.A. for something, I could still be listening to KCMU. Now of course you can just stream it, but I still have all these cassettes, and they’re filled with the greatest segues ever. … I think it’s called KEXP now, but it used to be called KCMU, “Music That Matters.” And it was.

Did you think about including other Seattle artists of the past?

If I’d had Quincy Jones music that had worked I would have put it on there. I like the whole idea of a Seattle lineage. That’s why Ann and Nancy are doing Led Zeppelin’s “The Battle of Evermore” [Led Zeppelin’s infamous “mud shark” incident was said to have happened in Seattle], and you know, the odd association for some was to bring Paul Westerberg in, but Westerberg seemed like a close cousin, and everybody loves the Replacements. I always like to be able to give exposure to the musicians that may not get their stuff into a movie quite as fast. I was very happy that [Mother Love Bone’s] Andy Wood got to hear his stuff in a movie – and not just as something coming out of a passing car, but as a real moment – and the Mother Love Bone guys got to hear that in Say Anything. In the same way I wanted to celebrate Westerberg. We did a video for “Dyslexic Heart” up in Seattle and everybody was happy to have him around.

You said Pearl Jam’s “State of Love and Trust” was like the soul of the movie. What was your relationship with the band like during the film?

Pearl Jam became Pearl Jam while we were making the movie. They were Mookie Blaylock when we started. When we started, they barely had a lead singer, I think they had just brought Eddie up from San Diego. Jack Irons had turned them on to Eddie’s audition tape, and they brought him up. So Eddie was kind of falling in love with them, and they were falling in love with Eddie, and it was fun to take Eddie into this world too; he was joining this band and playing bigger shows and then we gave Jeff Ament a job in our art department. And we used his font on the title cards in the movie, his hand-written font was so great. I think he’s still disappointed that his Joe Perry Project poster got stolen from the wall of one of the apartments [laughs].

What’s that story? He designed a Joe Perry poster?

No. So much of the stuff on the walls of Matt Dillon’s apartment in Singles was from Jeff Ament’s walls and his collection. I remember going to visit Jeff Ament – I would interview all these guys about their jobs and how they balanced their coffee-house jobs with their music careers – and I sat in Jeff’s room. He had this little apartment in downtown Seattle, and he had the greatest stuff on his walls: He had pages of music magazines, and exotic record-store promotional posters, and I just said, “Can we use all of this stuff in the movie?” And we did! We sort of imported it all into the movie. He had this precious Joe Perry Project poster, Joe Perry from Aerosmith, and somebody stole the poster. My dream is to find it, somehow, somewhere, and get it back to him, still.

One of the best bits of Singles lore I’ve heard is the story of the Ponciertape that Jeff Ament designed – which is coming out in full on this new edition of the soundtrack – and how all these actual songs were birthed out of it.

It’s kind of amazing. The idea was that Matt Dillon’s character, Cliff Poncier, in the course of the movie, he loses his band, and he loses his girlfriend, and he gains soul. So, there’s a period where he’s on a street corner busking, having lost his band, but beginning his solo career. And there would be, in reality, these guys standing on the corner outside the clubs in Seattle hawking their solo cassettes. So we wanted Cliff Poncier to have his own solo cassette. And Jeff Ament, in classic style, designed this cassette cover and wrote out these fictitious song names for the cassette.

And Chris Cornell was another guy who was close to us when we were making the record, and still is a good friend. I really loved Soundgarden; they were my favorite band. I originally thought Chris could play the lead, but then I think that turned into too big of a commitment for everybody and so he became the guy he is in the movie, but in the course of making the movie he was close to all of us. He was always around.

Anyway, Jeff Ament had designed this solo cassette which we thought was hilarious because it had all of these cool song titles like “Flutter Girl,” and “Spoonman,” and just like a really true-type “I’ve lost my band, and now I’m a soulful guy – these are my songs now” feeling. So we loved that Jeff had played out the fictitious life of Cliff Poncier. And one night, I stayed home, and Nancy, we were then married, she went out to a club, and she came back home, and she said, “Man, I met this guy, and he was selling solo cassettes, and so I got one for you.” And she hands me the Cliff Poncier cassette. And I was like, “That’s funny, haha.” And then she said, “You should listen to it.” So I put on the cassette. And holy shit, this is Chris Cornell, as Cliff Poncier, recording all of these songs, with lyrics, and total creative vision, and he has recorded the entire fake, solo cassette. And it’s fantastic. And “Seasons” comes on. And you just can’t help but go, “Wow.” This is a guy who we’ve only known in Soundgarden. And of course he’s incredibly creative, but who’s heard him like this? And we got to use “Seasons” on the soundtrack, and Chris did some of the score. And some of the unreleased score is on the new version of the album.

It’s kind of an example of how the community was close, still is close, and musically generous, and everybody is such huge music fans, that this would be the greatest joke to share with a buddy you can imagine. And obviously the music really holds up. He went and recorded “Spoonman” with Soundgarden and it was a big hit. It’s a statement about how when you’re not worried about somebody judging you or looking over your shoulder sometimes you do great stuff. And that’s the story of the fictitious Poncier cassette that became largely real.

Are there any moments in the film in which you were particularly psyched about the blending of a song with a scene? My favorite is when Campbell Scott is first showing Kyra Sedgwick his record collection and he says, “I was a DJ in college,” and then the next line of the soundtrack is “the DJ sucks!” in “Radio Song” by R.E.M.

Thank you for noticing that. I don’t think anybody has ever pointed that out. But I sure loved it when we did it.

I like when “Drown” comes in, the Smashing Pumpkins song. And in visuals, we had an extra reading the Lester Bangs book. I really loved being able to use the movie to put stuff in the corners of the scenes.

In the liner notes for this release, you write that songs like Blood Circus’ “Six Foot Under” “inspired you on set.” Would you literally be listening to that while filming?

Absolutely. [Sub Pop founder] Bruce Pavitt was doing DJ work in Seattle and I used to hear him play art openings or a restaurant or something, and he’s such a great DJ and he first played “Six Foot Under,” and I just loved it – those slow-moving, melodic guitars, I thought it was great. Truly was another cool band and had a record that we really wanted to have in the movie, and it just never fit, which is very strange. We had a song for Vanilla Sky that inspired the whole movie and we could never find a place for it, which was very frustrating. Julie Miller was her name, and “By Way of Sorrow,” was the song. And then with Elizabethtown there was a My Morning Jacket song called, “I Will Be There When You Die,” and that didn’t get anywhere. It’s not just about the words and the actors in the scene, it’s also about what kind of sonic landscape you’re going to fill.

Did you learn anything from putting together the Say Anythingsoundtrack that you brought to the Singles soundtrack?

That’s a good question. I started doing soundtracks with Fast Times at Ridgemont High, and I really, really loved how music could enhance a scene. And there was a moment when we had a scene that was kind of jarring that didn’t really work, and I found a song that worked in this one scene. I guess, there’s a scene about premature ejaculation in Fast Times and it’s kind of an awkward scene but there was this Jackson Browne song called “Somebody’s Baby,” that he’d written for the movie. And we didn’t know where to put it, and I tried it in this scene which seems kind of incongruous. But what it ends up doing is kind of capturing the whole anguished feeling of the scene and so this kind of upbeat song totally caught this guy’s embarrassment. And I was just hooked – I was hooked on the possibilities of music and film, and also I’d loved Mike Nichols’ stuff as a little guy, and he was the king for having used Simon and Garfunkel in The Graduate. And so this was like a little Graduate moment that happened. And Singles felt like an opportunity to really fly into the arms of that feeling. And Say Anything was one step further than Fast Times. And so then I started writing music into the stories more and then that opened the door for Almost Famous. There kind of has been a straight line through all of the movies that the music and choosing the music has been the secret love.

And by Singles you were also listening to music on set?

Yes, the breakthrough on Singles was to be playing the music on set. And then on Jerry Maguire we just started playing it during the scene. And Tom Cruise was really good with that. He would say, “Gimme the song!” And I’d play the song. And it became a little dance that was great. And then we did it again on Almost Famous and I hit a brick wall with Philip Seymour Hoffman. I put some Iggy Pop on during one of his scenes, and he was like, “Wait a minute, cut.” And I was like, “What?” And he says, “What makes you think that the music you’re blasting right now is better than what I have playing in my head?” And I was like, “Uhhh, nothing! Bad idea! Sorry! Done. All you, brother.” And it was a great experience working with him, but there was that one moment where I was like, “OK! Not everyone wants music played during their scenes” [laughs].

You also say in the liner notes that Alice in Chains dealt very well with the stops and starts of a production. Those live takes, did the bands get to play through a whole song?

Yes, they played through a whole song, because I didn’t want to do lip-synching, so Soundgarden is doing live “Birth Ritual” and Alice in Chains are playing live. They were great; they were very cooperative and fun. Somewhere around the time we were finishing the movie “Man in a Box” was a hit. They were the first band to score a hit out of Seattle in that generation. Layne [Staley] was wonderful. And we put Jerry Cantrell in Jerry Maguire. He’s the guy in the middle of the night in the copy store who tells Tom Cruise, “That’s how you become great, man. You hang your balls out there.” He’s the Jesus of CopyMat.

I’ve also read that you were partially inspired by the Alice in Chains song “Would?” – the first song on the Singles soundtrack, which was written in dedication to Andy Wood.

That’s true. Andy’s death and the feeling in the city after it was a real inspiration for the movie because the way I saw everybody pull together, it was that thing, it was the community of people who all live around each other, and they’re all single people, but together they form a disconnected family and that all happened the night Andy died and everybody just ended up showing up at Kelly Curtis’ house. They didn’t even call each other, they just started showing up. And I thought, “This just doesn’t happen in L.A.”

The Singles soundtrack was released almost three months before the film itself. Was that typical?

No, not at all. And that was the purpose. The purpose was to kind of chum the waters for people to know that there was a movie. And the music was very timely, and Pearl Jam hadn’t put out anything in awhile. Suddenly the child [the studio] didn’t want had become the favorite child, and they put out the soundtrack early. And it really helped.

A song like Mudhoney’s “Overblown,” with lyrics like, “Everybody loves us/ Everybody loves our town,” is a great example of that Seattle scene’s tongue-in-cheek relationship with fame.

“Overblown” definitely. “Overblown” is a bizarre example of getting spoofed by the godfather of the genre that made the whole thing an inside joke to some. That you could celebrate [Mudhoney’s] Mark Arm, and also finance his career, by him being able to write a song about being exploited.

Was it hard to get permission to use the Hendrix song in the movie?

It was. It’s much harder now, I think they’ve kind of clamped down in the ability to use Jimi Hendrix music, but I think we really kind of [got] down on bended knee. I think Kelly Curtis helped us out with Jimi Hendrix’s dad, who’s since passed away, but yes, it wasn’t easy at all. I love that song. It’s not the most played Hendrix song so I was happy that we were able to give it some exposure. Also Danny Bramson was extremely great, putting all that stuff together. He was the one who got so many of those clearances. And he talked Paul Westerberg into coming and being a part of it.

You mentioned in the liner notes that the acoustic version Paul Westerberg played you of “Dyslexic Heart,” included on this release, has often been the song you used to end mixtapes you’ve made for friends. That’s a pretty high honor, the proverbial Last Song on a Mixtape. Why that version of that song?

I love it. I think, to me, the spirit of the offhanded, not overthought, love of music is in that take. And also it ends with Westerberg saying “Broke my pick,” which … I love that studio chatter stuff. It’s always nice to have that little extra kiss. You blow a kiss goodbye at the end of a mixtape. It’s as important as the first song.

Even though you made Singles before the Seattle scene exploded, some people at the time were saying that you had made it after, to sort of cash in. What did that feel like?

A lot of people just go to movies and enjoy the entertainment, which is great. I had kind of forgotten a couple of things. You’d be amazed at how many people think actors make up the words in a movie. Like, “That Ryan Gosling is reallycool. That’s why he’s cool in movies: He says that stuff; that’s him.” And in a way it’s true. John Cusack puts his touch on everything. Yes, it’s true. But the other thing [I forgot] is that people don’t know how long it takes to make a movie, so when a movie came out in the first blush of the Seattle grunge explosion, not everyone knew that a movie doesn’t just get put out in two months. So some people were like, “Oh, Hollywood is capitalizing on grunge.” Meanwhile we had fought to get this movie out and it was on the shelf for nine months. When we had started out, that scene where I’m interviewing Matt Dillon was a real joke. There was no way the Seattle scene was going to be something that was an international, global issue. This was a joke about how self-important some musicians can be inside a very small scene. It might as well have been about the scene in Tulsa. But by the time the movie came out, [Seattle] had taken over the world. So we had to kind of tell people, “Really, this is a labor of love. It’s not us going out because Nirvana’s sold a zillion copies of Nevermind.” But anyway, time sorts it all out, so it’s good.

I’ve heard about a strange encounter you had with Mark Arm and him leaving and sending you “Overblown” afterwards. Was there any more to the story than that?

Not really, I was just happy that he came over, and he kind of looked around our offices and it felt like he sort of deemed us [to be] coming from the right place. And then later he sent us that song, which was super cool. I love Mudhoney and Mark Arm so I’m really glad that he chose to bless it in his own Mark Arm–ian way. Pretty much everybody there realized that it was coming from the right place and that serendipity caused the whole scene to sort of explode around it. I think the only people who were part of it originally and then pulled out were Nirvana, for a number of reasons. Part of it was maybe not wanting to be part of the crowd, and then maybe the other part was that they had been getting hit on by everybody at that point. But I heard later that Kurt and Courtney snuck in to the premiere, that somebody let them in through the exit door at the back of the theater, and that they came in and watched it. I always thought that was pretty great, that that night, Kurt Cobain was also in the room.

Was there a particular song of his that you intended to use?

I really liked “Immodium,” and I wanted to use that. That was the one that I thought belonged in the movie. … We were working towards it and I think I might have sent them a videocassette when Kurt was in Hawaii, I remember that. There was a time when we were just trying to figure out which of the songs would work. And then I found this cassette the other day in a box of stuff from Singles, when we were putting the expanded album together, and it said, “Nevermind: Early Mixes.” … So we were on track to have Nirvana in the movie too. I love that he saw the movie at the first possible moment.

Well, all of his friends were in it, right?

I guess, and some of his not-so-friendly friends. The whole concept for the soundtrack was definitely a mixtape that you would give to a friend, and not something that you would sell.

So why did you choose Smashing Pumpkins’ “Drown” as the Last Song on the Mixtape, for this soundtrack?

I love “Drown.” It was Chris Cornell who said, “We just got back from Chicago, we played a great show with this band Smashing Pumpkins, and you should check them out.” And I checked them out, and I really loved them. I spoke to Billy Corgan and asked him if he could send any new songs that we could consider for the movie. And he sent I think three songs, and “Drown,” was the last thing on it. It was long. The demo was pretty similar to the finished track. And immediately I loved “Drown” and it felt like the right kind of mood, and it fit. And I remember calling him up and saying, “I listened to these new songs, and I want ‘Drown.'” And his first response was, “Shit! I wanted to keep that one for myself.”

It has this long, beautiful, fuzzy outro that’s great for ending a Nineties mixtape.

It’s important. And to have it be just vulnerable enough, with that deniability put in if you’re giving it to somebody that you have feelings about. It’s always good to just graze the emotional issues. And “Drown” just seemed to work wherever we put it, and there was no place where “Drown” wasn’t where it should be. It felt like the right mood, exactly where we used it.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone – Alexis Sottile – May 18, 2017