Press – The Uncool – Seattle Times

Cameron Crowe’s new memoir details years as a young music journalist

Filmmaker and journalist Cameron Crowe comes off as an extraordinarily kind person, but he’s a little miffed that there’s no cultural inscription outside the Capitol Hill apartment complex central to his 1992 flick “Singles.”

“There were all these little shrines to ‘Sleepless in Seattle,’” he says, recalling his first stint in the Emerald City from 1986 to 1997. “Where’s our shrine?”

Crowe has a point. Though “Sleepless in Seattle” holds the titular edge between these films, it sports a disconnected jazz soundtrack and also takes place in Baltimore and New York. “Singles” distills Seattle’s musical apogee into 100 minutes of era-appropriate quirk. Does “Sleepless in Seattle” incorporate members of Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains and Soundgarden? It does not. Does “Sleepless in Seattle” feature SuperSonics power forward Xavier “X-Man” McDaniel issuing perhaps the greatest cinematic one-liner by any NBA player, ever? You get the point.

Crowe grew up in San Diego but was able to nail down Seattle’s musical ethos because he began his career as a prolific teenage music journalist, a story that turned into the autofictional 2000 film “Almost Famous.” He was also married to guitarist Nancy Wilson of Seattle band Heart from 1986 to 2010.

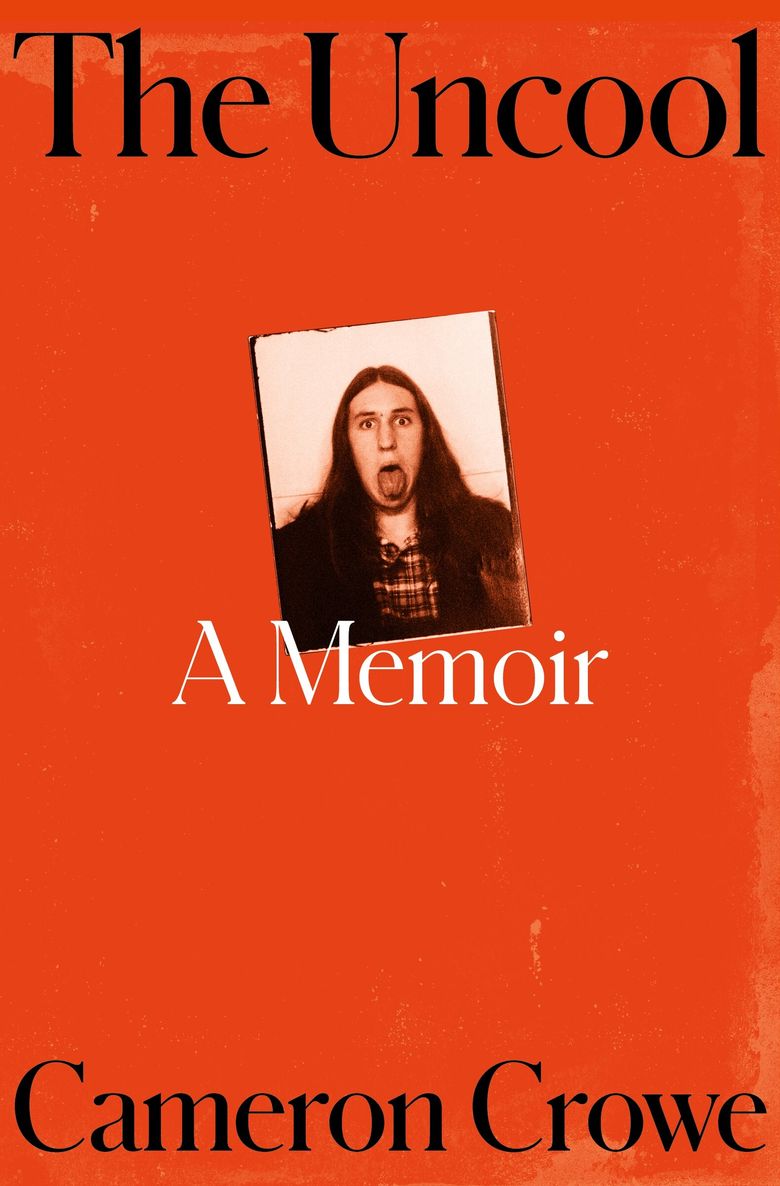

Crowe’s new memoir, “The Uncool” (out now from Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster), focuses on the pre-Seattle phase of his life, when a wide-eyed schoolboy found himself in greenrooms with the Allman Brothers Band, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie and countless other stars. It’s evident that the root of Crowe’s directing career, “Singles” included, lies here, in his love for music and the people that make it. Crowe will swing by Benaroya Hall on Nov. 17 to discuss the book with Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder.

Before he does, he spoke to The Seattle Times about some of his most famous interviews, the state of cultural journalism and the best kind of musical fandom. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I have to ask about this New York Times review of the book, in which critic Dwight Garner playfully accuses you of misrepresenting your “cool” credentials. Garner’s thesis is, if you hung out with all these rock stars as a teenager, how could you possibly be uncool? Your response?

I wish Dwight had hung around me, telling me that I was cool back in the day. Because I was not. The thing that helped me so much was I never wanted to be in the band. I was always the guy with questions. The fact that I was just there to do a job took me outside of the realm of the people that were trying to get in there and be one of them. The English journalists always used to kill me because they would dress like Keith Richards. That (New York Times) review was interesting. When I finished it, I thought, “Well, I think he likes it?”

There’s a great scene in here where you, as a young kid, see Bob Dylan play, and later in life, get to sit down with him and ask about that specific performance. He comes up with a fantastic line about the mercuriality of the 1960s. Can you talk a bit about that interview?

Joe Strummer (of the Clash) told (Dylan) it was a drag that he’d kind of missed the whole ’60s explosion. And Bob Dylan explained to him, and I guess to me, that it was like a flying saucer. You hear a lot about it, but very few people really saw it. I thought, (expletive) yeah. That is the best description of the ’60s. And it’s coming from him!

That interview happened at a red table in my house. I didn’t know that he wanted to do the interview in our little condo until about a half-hour until he showed up. So he sat at this strange red wooden table that really didn’t fit anything in our condo. It probably would have turned into kindling. But he sat down at the table and gave me that amazing interview. So I use it as my writing table. I kind of wrote “The Uncool” at that table.

The emotional complexity that you term “happy/sad” comes up a bunch in the book, initially during a high school heartbreak and later on in various music. How did that idea become central to your art?

It’s a feeling that I love. And you know, Seattle is a major happy/sad place. It’s like when the sunlight comes through. The drama of something is so much sweeter when it’s mixed in with an inappropriate laugh. I’ve been in situations where somebody is in a hospital, or, you know, they’re not doing well, they’re even dying, and I just feel like I want to tell jokes, and that feeling can spread through the room. That’s supreme happy/sad.

I think we all pick out our favorite songs based on how we grew up, how we were impacted, what happened when you heard XYZ song. And that ache is there forever. It’s one of my favorite things. I wanted the book to have that feeling. I think people thought, especially at the time, “He lives a charmed life. He’s just a kid, and he got on the cover of Rolling Stone.” But there were some serious knockdowns. I came home with my tail between my legs many a time.

Describing a staff meeting at alternative San Diego publication The Door, you recall this boundless youthful energy around local journalism and cultural writing. This feels remarkably foreign today. How do we start to reverse our trajectory?

It’s a really important thing to ask. But you can’t just ask it without kind of saying, it happened for a reason. Culture swept that era downriver, and it became much more of a huge moneymaking empire. And then, of course, it changed again when music became something you can get essentially for free. I think the main thing is, I always want to be able to celebrate the thing that happens when a band or an artist takes you to another place.

I love this quote from the book: “If you were a true fan, you owed an artist loyalty. You owed an important artist belief. If you love John Lennon, you ride out ‘Pussy Cats,’ knowing that around the corner can still be a ‘Beautiful Boy.’” Do you still feel that way about fandom?

The fun part of the fan experience is to take the big ride. People can disagree with you. You can argue with them. Fewer artists get a long career now, so maybe the point is moot. But the idea that you can put your chips down on an artist or actor or director or anything, and just say, “I’m with you, and I will celebrate the various stages of your career.” Joni Mitchell is an example of somebody that reinvented a lot. Bowie reinvented a lot. Some people jump off the train. But the ones that stay with it are true fans. I love the debates you can have about the artists that you love.

Courtesy of the Seattle Times – Eric Olson – November 11, 2025