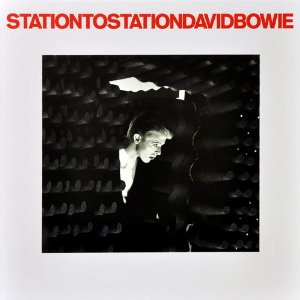

David Bowie – Station to Station

David Bowie stands in the dim shadows of Cherokee Studios. It’s a late fall evening, 1975. A single yellow light shines overhead. Hands in pockets, Bowie asks to hear the still-unfinished track he’s been working on. “Wild Is The Wind” fills the room with sound. It’s lush, and stark, and the track is nearing completion. He lifts an acoustic guitar and strums out a rhythm part, kneeling now, directly under that yellow light. The effect is strikingly cinematic, a marriage of sight and sound. Many a control room would be buzzing with meaningless chatter, technical conversation, or just plain small-talk. Not here. It’s silent here. Producer Harry Maslin watches quietly, riveted. Another cornerstone of the album is almost in place.

“What month is it,” Bowie asks a few minutes later.

“September,” offers his assistant, Corrine Schwab.

“Day?”

“25th.”

“A good day for ideas,” says Bowie. His hat cocked over his carrot-colored hair, a blonde streak at the center, for a moment he looks like young Frank Sinatra dipped in red-and-yellow ink. A minute later, he’s moved into the darkness and is dancing and clapping quietly to a playback of “TVC15.” (“It’s a song about a holographic television,” he confided. “The only piece of fiction on the album.”) My note from the night, on a scribbled scrap of paper, reads: “Snapshots. David Bowie lives his life as a series of perfectly staged snapshots.”

Station to Station, Bowie’s tenth album, was released early the next year. It’s a groundbreaking mix of rhythm and steel, from the icy slashes of the title track to the shuddering groove of “Golden Years.” Always passionate, sometimes even boldly emotional (“Wild is the Wind” is a stirring cover of a Nina Simone favorite), the recording remains forward thinking like no other album of its time.

Decades later, Station to Station still feels like a message from the future. Curious and fascinating in its day, it’s now easily among the artist’s best-loved works, a tantalizing stop at the crossroads, a watershed moment of creativity, and still mysterious in its origins. One of Bowie’s most important albums, the recording remains enigmatic to this day. The artist himself has little to say about it. When pressed in a 2006 interview, he remembered few details from the sessions. Station to Station was recorded in the midst of personal crisis, a period Bowie would later characterize as one which could have easily ended in tragedy. “It was probably one of the worst periods of my life,” he said. “It’s a blur, topped off with chronic anxiety, bordering on paranoia.” He laughed pointedly, with a strong measure of relief. The period was marked by drug use, spiritual frenzy, demos produced for his friend Iggy Pop, even a remarkable eleven-week film role in Nicholas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell To Earth, all during breaks in the recording of these six songs. The album remains precise and focused. It’s a glimpse of Bowie’s prodigious talents that even while previously claiming he was “finished with rock and roll, and rock and roll is finished with me”… he was re-defining it and providing a map for many an artist in the decades to follow.

Snapshot. It’s January, the next year. We’re on Bowie’s Isolar tour, several months before the fiery Nassau recording included on this set. (It’s a particularly strong night for the band, most of whom had come from the Station to Station sessions, and marked by some of Bowie’s warmest and expressive singing ever.) He’d settled on a new persona, the last one in the memorable series of characters that began with Ziggy Stardust. This one was severe and detached. The character was part alien, part cabaret figure. His name – The Thin White Duke. Bowie had even started an autobiography, The Return of the Thin White Duke. Boldly framed in strong white side-light, Bowie had reinvented himself again. The show began with a Dali short, Un Chien Adalou. The film washed over the crowd, provoking a stony cheer for its climax – an eyeball severed by a razor blade. Afterwards, back in the hotel room, Bowie asked to look at the tour itinerary. He’d dabbled in numerology as a kid, he said, and holding the list of upcoming shows, he proceeded to check off the dates that would be good, or a struggle, or yet-to-be-creatively-determined. He fired off a self-portrait too, and signed it. The portrait featured an arm, fingers outstretched, reaching out. Years later, with simple clarity: “It was a dangerous time. I was doing too much, with too small a handful of what one might call real friends.”

The danger brought with it a rigorous aesthetic. For Station to Station, Bowie worked hard on the sonic layers, often outlasting his band – led by Earl Slick on guitar, Carlos Alomar on bass and Dennis Davis on drums. “I’ve been wanting to record this song for three years,” he said another night at Cherokee, asking to hear “Wild is the Wind” again. One of the twin ballads on the record, he was still layering it with sound and emotion. “This has a good European feel,” he told me, as he finally finished the track. “It feels like a bridge to the future.”

The future was on David Bowie’s mind in almost every way. He eschewed the music of the laid-back California bands whose music permeated the airwaves of the day. He was already championing forward-thinking artists like Kraftwerk, the German band whose sound was driven by the earliest forms of computer age sampling and tape loops. For inspiration on the Isolar tour, Bowie would also keep returning to Brian Eno’s Discreet Music. Eno was on his itinerary of people to meet on the upcoming European dates. The plan was already forming in his head. Transition. Recovery. Renewal. Soon, leaving Los Angeles behind for good, Bowie would begin his late-seventies Berlin Trilogy with Eno as a collaborator. The bridge was in place. It had been an intense, and intensely creative year.

Long behind him now, Station to Station still resonates with purpose and delicacy. One of his most personal albums, it’s a diary of a life saved, set to a soundtrack of vision and soul. A masterpiece, disguised as a snapshot.

Cameron Crowe

June, 2010

Courtesy of EMI