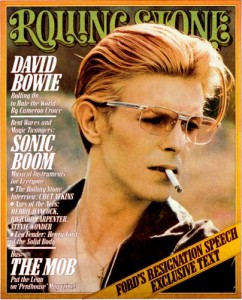

Rolling Stone #206: David Bowie

Ground Control to Davy Jones

Despite a new album and tour, David Bowie claims to have rocked his last roll.

Corinne Schwab is probably the last holdover from David Bowie’s glitter-glam phase – the days of Ziggy Stardust, Moonage Daydream, gaudy costumes, hulking bodyguards, ex-manager Tony De Fries and the back-room-at-Max’s-Kansas-City-mystique. In her three years as his secretary, Corinne has watched Bowie shrewdly work up to his most difficult move yet: the switch from cultish deco rocker to a wide-appeal and recording star/entertainer. “I want to be a Frank Sinatra figure,” Bowie declares. “And I will succeed.”

Wheeling a cart in a Hollywood supermarket just three blocks from where David is working on his new LP, Station to Station, Corinne says she has no doubts about something so obvious as Bowie’s success in achieving his stated goal. The way she sees it, David has only one problem. “I’ve got to put more weight on that boy,” she sighs. And with that she carefully places eight quarts of extra-rich milk in the basket.

Down the street at Cherokee Studios, David Bowie is just back from three vice-free months in New Mexico where he starred in Nick Roeg’s film, The Man Who Fell to Earth. He is still glowing from the experience and, says Corinne, the healthiest he’s been in years. He is relaxed and almost humble as he scoots around the studio and directs his musicians (Carlos Alomar and Earl Slick, guitars; George Murray, bass and Dennis Davis, drums) through the songs. It is a complete evolution from the David Bowie of six months before. But then, of course, anything less than a total personality upheaval would be entirely out of character for him. “I love it,” he cracked several months earlier. “I’m really just my own little corporation of characters.”

He is actually anything one wants him to be at any given moment – a paranoid hustler, an arrogant opportunist, a versatile actor, a gentleman, maybe even a genius. He had, after all, made a warning up front. “Don’t expect to find the real me…the David Jones [his true name] underneath all this.”

May 1975 — It’s four in the morning, Hollywood time, and David Bowie is twitching with energy. He’s fidgeting, jabbing a cigarette in and out of his pursed lips, bouncing lightly on a stool behind the control board in a makeshift demo studio, staring through the glass at Iggy Pop.

Bowie has spent the last nine hours composing, producing and playing every instrument on the backing track, and it is finally time for Pop to do his bit. After all, this is Iggy’s demo.

Bowie touches a button and the room is filled with an ominous, dirgelike instrumental track. The shirtless Iggy listens intently for a moment, then approaches the mike. He has prepared no lyrics, and in the name of improv, he snarls:

You go out at night from your sixty dollar single down in West Hollywood

With your ripped off clothes that are bulging

at the seams

I can’t believe that you don’t know you look ugly.

I mean, are you really all that dumb?

I mean, I don’t want you to be that dumb

you know.

But you are

You’re just dumb

Straight out of the cradle and into the hole with you.

He begins screaming.

When I walk through the do-wa.

I’m your new breed of who-wa.

We will nooowwwwwwww drink

to meeeeeee.

Bowie clutches his heart and beams like a proud father watching his kid in the school play. His whisper is full of wonder. “They just don’t appreciate Iggy,” he is saying. “He’s Lenny fucking Bruce and James Dean. When that adlib flow starts, there’s nobody like him. It’s verbal jazz, man!”

Pop himself is spent from his eruption; he listens only once to the completed cut and groggily proclaims it “the best thing I’ve ever done.” A woman acquaintance materializes, as if on cue, to drag him out by a handful of his platinum-dyed hair.

“Go and do what you will,” Bowie calls after them. “Just don’t be too long. We have a lot more work to do tomorrow.”

“Don’t worry,” Pop mumbles. “She never lets me kiss her anyway. Ever…”

“Good. Good.” David adds an afterthought. “Iggy, please keep healthy.”

Pop is still mumbling as he walks out the door. “I don’t believe my patience,” he says to no one in particular. “I just don’t believe my patience. She won’t even let me give her one little smooch…”

He leaves Bowie laughing, partly at the soporific anti-wit, but mostly over a successful effort at producing the unproducible.

Less than a minute later, Iggy Pop is the farthest thing from his mind. Bowie’s blanched, bony face has already fallen into furrows. “I am very, very bored,” he says.

But he is still charged up. He jumps to his feet, skips to the next room and straps on an electric guitar. This is Bowie the rocker and the image is striking. He stands under the studio’s deep blue light, dressed like a scruffy street corner newsboy from the Thirties, bashing on a bright orange instrument that perfectly matches the hair peaking out from under his cap. Over the next couple of hours, Bowie moves at break-neck speed. Before long he has written and recorded a new song and entitled it “Movin’ On.” Only three months before, he and John Lennon had come up with the Number One single “Fame” in only 45 minutes. “Another song,” he groans. “That’s the last thing I need. I write an album a month as it is. I’ve already got two new albums in the can. Give me a break.” He is happy. It’s 7 a.m. and David Bowie is finally content as he locks up the studio.

Driving a borrowed VW bug through sluggish morning traffic toward the Hollywood Hills, his eyes never stop scanning the streets. He thrills over the massage parlors, billboards and stumbling itinerants. “L.A. is my favorite museum,” he says.

Bowie had fled New York by train (he does not fly) only five days earlier. After the numerous lawsuits, countersuits and injunctions over his split with manager Tony De Fries and the MainMan Companies, New York, he says, began to “close in on me.” Now he is staying at the home of Deep Purple bassist Glen Hughes. While Purple is on tour, he’s been living there with Hughes’s housekeeper, Phil. When he lets himself into the house, David finds a stranger, Phil’s houseguest, drunk and half asleep on the sofa.

Bowie extends his hand tentatively. “Hello, I’m David. Who are you?”

The stranger is quickly aroused. Looking exactly as if he’d just awakened to find David Bowie standing in front of him, he pumps his hand wildly. “I’m Jack,” he says. “Hey man, fucking-A great to meet you. Phil told me you were staying here too. He’s asleep now…so how you fuckin’ doin’ anyway?”

After a quick breakfast spent dodging inquiries (“I hear you only play soul music now. That true?”), Bowie graciously explains that he’s late for an appointment. He leaves the house, hops into the car and shrieks: “Oh my God, what a cretin! He’s totally wrecked my nerves, that oaf! Christ!” He calms down and politely begins easing out of the planned interview — his first in more than three years. He begs exhaustion after two full days without sleep. “Why don’t I just drop you off at your hotel and we can get together next week?” He has already swung into the direction of the Beverly Wilshire. “You know, I may even check myself into the hotel for a day of sleep. No one will know where I am, no one will bother me…yes, that is exactly what I’ll do.” At the front desk, however, he hears that guitarist Ron Wood is staying in Room 207, and Bowie decides to pay his old friend a visit. He procures a fine champagne and raps on the door.

Wood has just fallen asleep, but is glad to see Bowie nonetheless. They exchange stories on what they’re up to in L.A., then settle down to listen to a cassette of the Jeff Beck Group live at Detroit’s Grande Ballroom. Sprawled across the hotel room bed, Bowie is by now well into his fifth or sixth wind. And the interview on. “Well,” he asks, “what do you want to talk about?” One mentions the MainMan lawsuits.

Bowie’s speech assumes a quiet, studied tone. “The split had been building up for some time. For the last year and a half, I’ve had no empathy with them whatsoever. It took me that long to stop touring and come back to finding out where the office was really at. I guess it was a bit hard for them to come to terms with what I wanted to do. A lot of people who I never even met got involved. I grew to dislike their attitude. So I just said goodbye. No, of course, it isn’t that simple, but I’m going to make it that simple. It’s not going to bother me. I’ll survive. I’m far from broke. I’m free.” (Reached at the New York MainMan offices, De Fries refused to comment.)

“I’ve never been so happy,” Bowie says. “I’ve got that good old ‘I’m gonna change the world’ thing back again. I had that once. I was a strong idealist once, then when I saw all my efforts being mistranslated, I turned into an avid pessimist. A manic depressive. Now I feel strong mentally again. You could probably hear from Young Americans that I’m on an upper. It’s the first record I’ve actually liked since Hunky Dory.

“Basically I haven’t liked a lot of the music I’ve been doing the past few years. I forgot that I’m not a musician and never have been. I’ve always wanted to be a film director, so unconsciously the two mediums got amalgamated. I was trying to put cinematic concepts into an audio staging. It doesn’t work.”

At the time, Bowie had already signed the contracts for his film debut in The Man Who Fell to Earth. Not that director Nick Roeg (whose previous credits include Far From the Madding Crowd, Walkabout, Don’t Look Back and Performance) had an easy time but was fascinated by the fact that Roeg had waited eight hours for him after he forgot an appointment. The two held an eight-hour conversation lasting into the next afternoon and Bowie was sold. “It didn’t take long for me to realize the man was a genius. He’s at a level of understanding of art that tremendously overshadows me. I was and still am in awe of Roeg. Total awe.” Still, parts of the script were rewritten.

Before he fell to earth, Bowie had been reported ready to star with Elizabeth Taylor in Bluebird. “I never said that,” David counters, “Elizabeth Taylor did. It was her idea for me to be doing the film. I read the script through and it was very dry. I mean she was a nice woman and all, even if I didn’t get much of chance to get to know her. She did tell me I reminded her of James Dean – that endeared me to her – but her script was so…boring. My own films are more important anyway.”

Bowie has been voraciously writing screenplays and scenarios ever since the three-month Diamond Dogs tour of two years ago. His first completed script is Dogs, a film which could star Terence Stamp and Iggy Pop if Bowie can work it out. David is especially amused by his casting. “Terence is going to be Iggy’s father,” he titters. “Isn’t that lovely?” I can’t wait to direct it.”

“I think, you see, that the most talented actors around are all in rock & roll. Iggy never should have been a rock & roll singer, he’s an actor. Dave Johansen [the former New York Doll] is an actor. A renaissance in filmmaking is going to come from rock. Not because of it, but despite it. I’ll tell you, I’ve got nothing to do with music. I’ve always interpreted or played roles with my songs.”

Ron Wood, who’s been quietly listening all along, comes alive. “Why did you get into rock & roll, then?” he asks.

“Rock & roll is a very accessible medium for many young artists. Don’t you think so? I like music but it’s not my life by any stretch of the imagination. I mean I was a painter before, but as a painter I couldn’t make enough money to live. So I went into advertising and that was awful. That was the worst. I got out of that and tried rock & roll because it seemed like an enjoyable way of making my money and taking four or five years out to decide what I really wanted to do. I have no ideals on being a starving artist at all.”

“Same as me,” Wood chortles. “Otherwise we’d both still be in art school, eh?”

“Absolutely.” Assured that Wood is an interested listener, Bowie settles into a monologue:

“It’s interesting how this all started. At the time I did Ziggy Stardust, all I had was a small cult audience in England from Hunky Dory. I think it was out of curiosity that I began wondering what it would be like to be a rock & roll star. So basically, I wrote a script and played it out as Ziggy Stardust onstage and on record. I mean it when I say I didn’t like all those albums — Aladdin Sane, Pin Ups, Diamond Dogs, David Live. It wasn’t a matter of liking them, it was ‘Did they work or not.’ Yes, they worked. They kept the trip going. Now, I’m all through with rock & roll. Finished. I’ve rocked my roll. It was great fun while it lasted but I won’t do it again.”

One can assume then, that Bowie is asking for a separation from the “Glitter Rock King” tag?

David is offended by the notion. “Not at all. I’m very proud of that tag. That’s what the public’s made me and that’s what I am. Who am I to question that? I am the King of Glitter Rock, aren’t I, Ron?”

“The reigning king.” Wood goes to his writing desk and scribbles. “I don’t like giving people tags,” he cackles, “but here. For the king.” He hands Bowie a $15 price tag, on the back of which he’s written “King of Glitter Rock.”

“Fifteen dollars!” Bowie deadpans. “Well, I guess glitter rock was always cheap anyway.” A full minute is spent in laughter, then Bowie abruptly turns skittish and paranoid. “I keep drifting off.” He admits to being tired. “My thought forms are already fragmented, to say the least. I’ve had to do cutups on my writing for some time so that I might be able to put it all back into some coherent form again. My actual writing doesn’t make a tremendous amount of sense…frankly, I’m surprised Young Americans has done so well. I really, honestly and truly, don’t know how much longer my albums will sell. I think they’re going to get more diversified, more extreme and radical right along with my writing. And I really don’t give a shit….” Finally Bowie bows:

“Could I have a little break? I can’t go on like this. Just sitting here talking…it wears me out.”

June 1975 A straw hat cocked lazily over one eye, David is sitting cross-legged against the wall in a small, candle-lit, book-lined room. The framed cover photo from Aladdin Sane hangs above his head in direct juxtaposition. It is one of his favourite ploys striking not only poses but whole portraits.

It’s been three weeks since the last meeting, and he’s moved from Hughes’s house into the more centrally located Hollywood home of lawyer and former booking agent Michael Lippman. Bowie and lggy never did make it back into the studio. Pop slept past the booked time, called up drunk several nights later and when Bowie told him to “go away” — meaning “hang up” — Iggy did just that. Now he’s disappeared. “I hope he’s not dead,” says Bowie, “he’s got a good act.”

Bowie announces that he’s got a new project, his autobiography. “I’ve still not read an autobiography by a rock person that had the same degree of presumptuousness and arrogance that a rock & roll record used to have. So I’ve decided to write my autobiography as a way of life. It may be a series of books. I’m so incredibly methodical that I would be able to categorise each section and make it a bleedin’ encyclopedia. You know what I mean? David Bowie as the microcosm of all matter.”

If the first chapter is any indication, The Return of the Thin White Duke is more telling of Bowie’s “fragmented mind” than of his life story. It is a series of sketchy self-portraits and isolated incidents apparently strung together in random, probably cutout order. Despite David’s enthusiasm, one suspects it may never outlast his abbreviated attention span. But it’s a good idea. At 29, Bowie’s life is already perfect fodder for an autobiography.

The son of a children’s home publicist, David Jones grew up prowling the tough neighbourhoods in the south of London. One fistfight paralysed his left pupil. Today, caught at a certain angle, it looks like a clear marble. Eye operations kept him prostrate for the better part of his 16th year. During the same bedridden time, his brother Terry, six years David’s senior, was committed to a mental institution. It was then, he remembers, that he began to draw up the blueprint for David Bowie.

“Who knows? Maybe I’m insane too, it runs in my family, but I always had a repulsive sort of need to be something more than human. I felt very very puny as a human. I thought, ‘Fuck that. I want to be a superman.’ I guess I realised very early that man isn’t a very clever mechanism. I wanted to make better. I always thought that I should change all the time … I know for a fact that my personality now is totally different to what it was then. I took a my thoughts, my appearance, my expressions, my mannerisms and idiosyncrasies and didn’t like them, so I stripped myself down, chucked things out and replaced them with a completely new personality. When I heard someone say something intelligent, I used it later as if it were my own. When I saw a quality in someone that I liked, I took it. I still do that. All the time. It’s just like a car, man, replacing parts.”

Bowie learned to apply this theory to his music. “If I’d been an original thinker, I’d never have been in rock & roll. There’s no new way of saying anything.” He recalls himself as a “trendy mod” through his late teens. “I was never a flower child. Look what’s happened to them with all their love and peace. They’ve grown up into the SLA, kidnapping Patty Hearst and the like. I’d been into meditation years before it became fashionable through Kerouac and Ferlinghetti. I was always a sort of throwback to the Beat period in my early thinking. And when the hippies came along with all their funny tie-dyes and things, it all seemed naive and wrong. It didn’t have a backbone. I hate weak things. I can’t stand weakness. I wanted to hit everybody that came along wearing love beads.

“I never got into acid either. I did it three or four times and it was colourful, but my own imagination was already richer. I never got into grass at all. Hash for a time, but never grass. I guess drugs have been a part of my life for the past ten years, but never anything very heavy … I’ve had short flirtations with smack and things, but it was only for the mystery and the enigma. I like fast drugs. I hate anything that slows me down.”

A high school dropout. David had already changed his name and gone through a number of pop groups when he met his wife Angela. She was the girlfriend of a Mercury Records talent scout who refused to sign David. Later, she pulled strings and he got a contract with the label. Within months he had a hit with his first single, “Space Oddity”. “I married her,” David explains, “because she was one of the few women [his emphasis] that I was capable of living with for more than a week. We never suffocated each other at all. We always bounced around. No, I don’t think we fell in love. I’ve never been in love, thank God. Love is a disease that breeds jealousy, anxiety and brute anger. Everything but love. It’s a bit like Christianity. That never happened to me and Angie. She’s a remarkably pleasant girl to keep coming back to and, for me, always will be. I mean there’s nobody … I’m very demanding sometimes. Not physically, but mentally. I’m very intense about anything I do. I scare away most people that I’ve lived with.

In 1971, the Bowies had a son, named Zowie. Having a child, Bowie says, “pleased my ego a lot. I think Zowie’s a survivor. He’s very definitely an independent person, of his own choosing, it seems. And I find it quite easy to think of him not as mine or as Angie’s, but as Gibran has said, ‘a little plant.’ I don’t feel very paternal about him.”

Bowie adamantly states that he is still and always will be bisexual. And he will not deny that he has fully exploited the media potential of that. “I remember the first time it got out. Somebody asked me in an interview if I ever had a gay experience and I said, ‘Yes, of course, I am a bisexual.’ The guy didn’t know what I meant. He gave me this horrified look of ‘Oh my God, that means he’s got a cock and a cunt.’ I had no idea my sexuality would get so widely publicised. It was a very sort of off-the-cuff little remark. Best thing I ever said, I suppose.”

He returns to the subject of his autobiography: “It’s not that I have anything to say, it’s a matter of laying antistyle on people and making them upset. Who the hell is Bowie to think he deserves an encyclopedia?’ But it’s not what you actually put on the canvas, it’s the reason why you did it. Like the Andy Warhol thing. It wasn’t why he painted a Campbell’s soup can. It was ‘What sort of man paints a Campbell’s soup can?’ That’s what aggravates people. That’s the premise behind antistyle. And antistyle is the premise behind me.

“I already consider myself responsible for a whole school of pretension. Really. I’m quite serious about that. The only thing that seems to shock anybody anymore is something that’s pretentious or kitsch. Unless you take things to extremes nobody will believe or pay attention to you. You have to hit them on the head and pretension does the trick. It shocks as much as a Dylanesque thing did ten years ago.”

Suddenly – always suddenly – David is on his feet and rushing to a nearby picture window. He thinks he’s seen a body fall from the sky. “I’ve got to do this,” he says, pulling a shade down on the window. A ballpoint-penned star has been crudely drawn on the inside. Below it is the word “Aum.” Bowie lights a black candle on his dresser and immediately blows it out to leave a thin trail of smoke floating upward. “Don’t let me scare the pants off you. It’s only protective. I’ve been getting a little trouble from … the neighbours.”

Something has triggered the emergence of another David Bowie – the apocalyptic theoriser in albums ranging from Ziggy Stardust to Diamond Dogs. “I think we are due for a revival of God awareness. Not a wishy-washy kind of fey, flower-child thing, but a very medieval, firm-handed masculine God awareness where we go out and make the world right again. I’m feeling more and more that way.

“Rock & roll has been really bringing me down lately. It’s in great danger of becoming an immobile, sterile fascist that constantly spews its propaganda on every arm of the media. It rules a level of thought and clarity of intelligence that you’ll never raise above. You don’t have a fucking chance to hear Beethoven on any radio station anymore. You’ve got to listen to the O’Jays. I mean, disco music is great. I used disco to get my first Number One single [“Fame”] but it’s an escapist’s way out. It’s musical soma. Rock & roll too-it will occupy and destroy you that way. It lets in lower elements and shadows that I don’t think are necessary. Rock has always been the devil’s music. You can’t convince me that it isn’t.”

How about specifics? Is Mick Jagger evil?

“Mick himself? Oh Lord, no. He’s not unlike Elton John, who represents the token queen, like Liberace used to. No, I don’t think Mick is evil at all. He represents the sort of harmless, bourgeois kind of evil that one can accept with a shrug.

“I’ve got this thing that rock shouldn’t be overstated. I did my bit of Ziggy, I made my explosion and that’s it. When the artist and song is novel and new and enigmatic, then that’s good. That’s when it’s strong it has a familiarity and understanding, it’s no longer rock & roll.

“I wasn’t all surprised Ziggy Stardust made my career. I packaged a totally credible plastic rock star than any sort of Monkees fabrication. My plastic rocker was much more plastic than anybody’s.

“I fell for Ziggy too. It was quite easy to become obsessed night and day with the character. I became Ziggy Stardust. David Bowie went totally out the window. Everybody was convincing me that I was a Messiah, especially on that first American tour. I got hopelessly lost in the fantasy. I could have been Hitler in England. Wouldn’t have been hard. Concerts alone got so enormously frightening that even the papers were saying, ‘This ain’t rock music, this is bloody Hitler! Something must be done!’ And they were right. It was awesome. Actually, I wonder … I think I might have been a bloody good Hitler. I’d be an excellent dictator. Very eccentric and quite mad.

“I was thinking a few days ago that when I got bored with films and had far too many showings in art galleries of my paintings and sculptures, maybe I should be prime minister of England. I wouldn’t mind being the first English president of the United States either. I’m certainly right wing enough. Do you think Jerry would swap positions with me? I think that would be lovely, don’t you?”

Chain-smoking Rothman after Rothman, Bowie is now just spilling words and concepts out without regard for their ramifications. His sole target now is impact. Shock. Effect.

“Listen, I mean it. I’ll bloody lead this country, make it a great fucking nation. I can’t exist happily and make records and be safe because, man, it’s depressing… Everyone whimpering about the state of things. So what do I do? Just sit by and wait for someone else to sort it all out? No way. The masses are silly. Just look at the cultural leaders of today. Once they were Humphrey Bogart, James Dean and Elvis Presley. Now it’s Robert Redford and John Denver… and these are supposed to be the degenerate Seventies. It doesn’t look good for America. They let people like me trample all over their country.

“I have this dream. I’d like to host a satellite television show and invite all the biggest bands onto one stage. Then I’d come out with a great big wheelbarrow of machine guns and ask them, ‘Now how many of you are gonna do anything? How many are going to pick up a gun and how many of you are gonna cling to your guitars?’ ”

Before he can pick up the thread again one feels the need to question Bowie on the seriousness of his tirades. He answers with an impatient huff that seems to ask, how much longer will it take you silly mortals to understand? “I have to carry through with my conviction that the artist is also the medium. The only way that I can be this abrasive as a person is to be this confoundedly arrogant and forthright with my point of view. I can only do that by believing in my point of view with sincerity. And I do. I honestly believe everything that I’ve said. I believe that rock & roll is dangerous. It could well bring about a very evil feeling in the West. I do want to rule the world.

“There’s always a pendulum swing, right? Well, we’ve had the high with rock. it’s got to go the other way now. And that’s where I see it heading, bringing about the dark era. That we weenie boys with our makeup and funny clothes and whatnot, I feel that we’re only heralding something even darker than ourselves. ‘Cause we were never dark ourselves. We just bounded around the periphery. Lou [Reed] is not evil. Iggy isn’t evil. There’s something else. And it’s evil because it supplements people’s sensitivity. Just look at Led Zeppelin. Our natural inclination to be adventurous with our brains is being repressed. I don’t like or approve of loud rock & roll.”

That’s why he broke up his backing group, the Spiders from Mars. “I gave them more life than I intended. And I was also getting honestly bored. There’s only so much you can do with that kind of a band. I wanted no more to do with that loud thing. Hurt my ears. Wasn’t pleasing my mind too much either. Since then, poor Mick [Ronson] has completely missed his vocation. From his faulty solo career right on down. I’ve been disappointed. He could have been amazing. I just don’t know. Christ, I haven’t spoken properly with him in years. I wonder if he’s changed.”

One reminds Bowie of a remark Ronson made to Melody Maker that “David needs someone around him to say ‘Fuck off, you’re stupid.’ He needs one person who won’t bow to him… ”

Bowie grins. “I’ve got God. Who’s Mick got?” He turns stern. “I promised myself I wouldn’t talk about rock & roll. Now look what I’ve done. Let’s talk about something else.” He picks his appearance on the Grammy awards as the next topic. “Did you see it? It’s on videotape in the next room if you didn’t. You really should see it. It’s only a minute. You see, the Grammys were very significant for me. It was like walking a tightrope. There were mostly aging middleclass show business people in that audience. It was a question of entertaining them or coming off like just another rock singer. I really did feel I was David Bowie and not a rock singer. It was very strange. Strange, strange, strange.

“There are very few who have broken out of rock and into any other medium, much less films. I’m determined to do it. The media should be used. You can’t let it use you, which is what is happening to the majority of rock stars around. And as for touring, I honestly believe that it kills my art. I will never ever tour again.”

Several months later, Bowie apparently changed his mind and announced that on February 2nd he would kick off a 34-date North American tour. “The tour,” Bowie explained, “will make an obscenely large amount of money which I desperately need to set up my media-production company, Bewlay Bros.”

The tour is a turnabout for Bowie; the production company is consistent with his previously stated goal of breaking the “dreaded circle” of being a star enmeshed in the music business. “I’m optimistic enough to think that of any rock singer, I’ve got a better chance of escaping. One person who I admire, quite honestly, is Frank Sinatra. He’s broken out. He hates the fucking music business game and so do I. I refuse to play it. I’ve never made an album capitalising on the success of the previous one.

“I want to make an impact on myself. I’d much rather take chances than stay safe. Like in the movie I’m doing. Everything’s is against me. I’m going into a dead straight, nonmusical role. No singing. And I will be bloody good. I have to be. ‘Cause if I ain’t, that’s it. Another rock singer… is still a rock singer. If that’s the case, I want to go out like Vince Taylor.”

Vince Taylor?

“Yeah. He was the inspiration for Ziggy. Vince Taylor was an American rock & roll star from the Sixties who was slowly going crazy. Finally, he fired his band and went onstage one night in a white sheet. He told the audience to rejoice, that he was Jesus. They put him away.” David Bowie straightens up, removes the straw hat and rakes several fingers through his orange hair.

“Think you can use any of that?”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #206 – Cameron Crowe – February 12, 1976