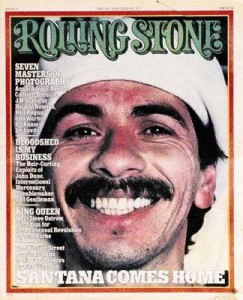

Rolling Stone #212: John Fogerty

John’s Clearwater Credo

Proud Fogerty Post-Creedence

Troy, Oregon – At first he is unrecognizable. With an oversized cowboy hat tipped over his short brown hair, he twangs out “Born on the Bayou” from the town hall bandstand. Then, looking up and pointing a finger into the tiny crowd, John Fogerty lets loose with the old Creedence howl and shouts out the last verse. A beery roar goes up from the entire town of Troy, pop. 27. It’s Saturday night and their star resident is treating everybody to a dance.

When Creedence Clearwater Revival announced their official breakup in 1972, they had just returned from a sold-out world tour to rack up their seventh gold album (Mardi Gras) in as many tries. Rock went on to lose much of the innocent charm that Creedence once embodied, but the field seemed more than open for Fogerty’s solo career. He had been the heralded author, bandleader, arranger, producer, guitarist and singer behind a three-year stream of gold CCR hits like “Proud Mary,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Lodi,” “Fortunate Son,” “Down on the Corner” and “Sweet Hitchhiker.”

But the hits ended along with the band. Bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug “Cosmo” Clifford played with Doug Sahm and are now backing singer Don Harrison in Berkeley. Rhythm guitarist Tom Fogerty is still plugging away – after four miserable-selling solo LPs – with his new Bay Area band, Ruby. Of them all, John Fogerty has the highest hopes.

“I’ve just survived a period in my life I thought I’d never go through,” he explains. Fogerty looks like a survivor: at 30 he is sturdier, huskier and far more rugged-looking than ever before. “All those years of hearing about how Monk and Miles and the Duke got screwed and became disillusioned with their careers… I always used to say, ‘That’s dumb. That’ll never happen to me. I’ll never stop making records.’ And then… it all happened to me.”

Before John Fogerty was released last year on Asylum Records, he had recorded only one post-Creedence LP – an album of country & western standards called The Blue Ridge Rangers. While he played every instrument, his name appeared nowhere on the album. Released in ’73, it was originally meant as an immediate prelude to “making real solo records.” Instead, Fogerty found his ties to Fantasy Records, who’d lost their most successful act to the Creedence breakup, too constricting. “So I stopped.”

In Berkeley, Fantasy Records president Ralph Kaffel sees things differently. “We had a good relationship during the Blue Ridge Rangers album. He called all the shots and basically wrote his own ticket for everything. When he finally put out a record under his own name – ‘Comin’ Down the Road’ – it bombed. Even though we did not drop the ball. I think he held us responsible.”

Fogerty spent the majority of a three-year “strike” against the label enjoying family life with his wife and three kids. He stepped onstage only once, with Tony Joe White at San Francisco’s Boarding House nightclub. Beyond that, Fogerty kept himself largely insulated from the music business. Glitter rock? Hotel destruction? The Tubes?

“Gee whiz… is all that stuff really important these days?” Fogerty looks genuinely surprised. It’s Monday afternoon now and he’s taking a break from building his half-finished lakeside retreat here in the lush wilds of Oregon. “I don’t identify with any of that stuff at all. I guess there’s a very little that I do identify with. Here I am, a San Francisco musician, brought up through the Fillmores in the golden age of Haight-Ashbury… and there’s never been anything I identified with there.”

John Fogerty has never performed stoned. He has never drunk more than four beers or one glass of wine in a single sitting. He can count his marijuana highs on one hand and has never taken acid. “I’m still very touchy about drugs,” he says. “I could only see them as a threat to a career. I didn’t want to go back to the gas station. I still maintain that all that stuff is self-destructive and not conducive to good music. I’ve known two or three heavy dopers in my life. They smoked a lot of grass. Heavy. And I’ve seen nothing to make me emulate it at all.”

“I suppose I should be ashamed [of never taking acid] or something. But I didn’t want to be 30 and driving down the freeway when suddenly a little part of it hits me again. No drinkin’ and no dopin’ – that’s always been my policy.”

The credo wasn’t quite so successful with the other CCR members. “Looking back… and this is old father Fogerty talking… I don’t know how to say it… the first time I realized I was being naive, I was really disappointed. I’d see them grinning at each other the next day, but it took me a year and a half to catch on. They were getting loaded in their hotel rooms after the show.”

All this piety only underscores the fact that John Fogerty is a fanatically self-designed rock & roll star, in the classical sense. Three years ago, for example, he was especially nervous about the legacy he would leave behind. After all, Jimmie Rodgers had died in ’33, Hank Williams was killed in ’53, and in ’73… “I figured it was my turn.”

Fogerty figures he lost his musical virginity to Elvis’s first album when he was 11. Around that time he also read an interview with Carl Perkins that changed his middle-class life. “He said his goal was just to dance and sing and play the guitar. To me, that’s the whole point of being a rock & roller.” His eyes glaze in reverence. “The stage was all that mattered then. None of this other crud – whether you had ten Lear jets, how well you pose for pictures, how well you spend your money… none of this stuff that’s all considered part of being a star now. I have no way of understanding that… well, maybe a little bit. Geez, I always did want to play the Fillmore in my goddang gold lame shoes and glitter suit. I never got the chance.”

The end of CCR came as a result of – and Fogerty does not dispute this fact – the other three members demanding that power be distributed more equally. Brother Tom left the band after Pendulum for his own career. Cook and Clifford stayed on to write and sing two-thirds of Mardi Gras, which was something less than an artistic coup. “We toured a couple times after that and it was like watching the flag getting dragged in the mud,” says John. “I’ve thought of it many, many times… that’s the exact picture I had of it. A tattered and torn flag… we all felt it. We should have just broken up right away and left a good memory.”

“I figured that Creedence made six albums. Let me count… the first one, Bayou Country, Green River, Willy and the Poor Boys, Cosmo’s Factory, Pendulum… yeah, six. I wouldn’t seven-count Mardi Gras and neither would anybody else. I had no control over anything after that. The rest is horse manure. Baloney.”

“I never thought Fantasy would release all that they did. Here I was with a solo career, supposedly, and they’re putting out Creedence records faster than I could make my own. All the old stuff kept coming… Gold, More Gold… next thing to come will be Creedence in E. They’re gonna go on forever. They released a live album, something I had sworn would never happen. And I had the solemn promise from Saul Zaentz, the president, that The Golliwogs [a scrappy collection of early demos] would never, ever be released. We were ashamed of it. They put it out last year. It just wasn’t fair. At the time, we were the only ones who cared about getting them made. They [Fantasy] didn’t know anything about pop music. They still don’t. It’s like the guys up here have a whole thing with rodeo riders, a million names that we could never even come close to remembering. That’s how foreign pop was to Fantasy.”

Zaentz, who is now chairman at Fantasy, was tied up with preparations for the company’s appearance at the Academy Awards on behalf of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which Fantasy produced. So it is Kaffel who again rises to the company’s defense:

“Because of the importance of Creedence as a contemporary rock band,” he says, “The Golliwogs was released primarily as an historical document. There was no attempt to sweeten the sound or to pass it off as a Creedence Clearwater Revival album, and it didn’t sell a damn.”

Fogerty is definitely not a Fantasy fan. “They must have propagated the rumor that we owned the label, so other labels couldn’t be making overtures. We got approached very, very little in our career. I think it might have happened twice. Everyone must have figured we had this gravy deal. I remember the one time we asked for a raise, they whipped out a ten-year contract.”

One person who did call was David Geffen, an aspiring agent for CMA at the time. Fogerty thanked him but gruffly explained his low regard for Geffen’s trade. Eight years later, then chairman of Elektra/Asylum, Geffen called again. Fogerty laughs at the memory. “It was the very week all my problems with Fantasy started, so I told him I couldn’t talk and to call back in a month. I brushed him off again.”

Exactly one month later, the phone rang a third time. “I told him all the reasons why I wasn’t doing anything and Geffen says, ‘Okay, we’ll buy the company.’ I was shocked. ‘I wouldn’t want to own that company,’ I said. ‘Everything they touch turns to lead.’ So he said, ‘Well, we’ll just buy your contract.’ Which is eventually what happened….”

Like most people attempting one, Fogerty loathes the word “comeback.” Sitting on the bank, staring out into the river that cuts through Troy, he tries to pinpoint his distaste for the term. “I guess it’s because I always hate it when Sammy Davis ‘retires’ and then has a comeback. Then he has a farewell tour and then a comin’ back tour. After six or seven times of hearing that, you start to attach some distrust….”

The other reason, of course, is that few artists actually succeed in their comebacks. And Fogerty never did like the smell of failure.

“I never went through the years and years of paying club dues. Creedence wasn’t actually a performing band until about six months before we made it. Even when we did play bars, we did it under a name other than CCR. I mean, when did you walk into a bar and say, “Boy, someday those guys are gonna be huge.’ You figure that’s the best they can do. And you’re right.”

But John has a way of rationalizing the poor sales of last year’s John Fogerty. “It’s really hard for a guy to be away for a certain amount of time and come back at full creativity. That’s not an excuse, believe me. That’s truth. It’s difficult to get all the juices flowing again. The situation is very much like the first Creedence album. I had to make that album they way I did. Looking back, I would change almost everything on it. But I had to do it to get to this next album. There were times when I thought I really hated that record… but it’s all right. I like it.”

“It was a pretty narrow existence,” he reflects, “trying to keep the success going. Trying to stay at the pinnacle. Here you thought you were striving your whole life to get to the top, then once you get there you realize that isn’t what you really wanted. Everybody has a different way of saying what a letdown it is. So I feel comfortable. A little itchy to get back into it, but comfortable. I mean, if I hadn’t succeeded, I’d still be trying to make it. It’s as simple as that. I was pretty intense about trying to make it… who knows, I might’ve still been trying at 50. I’m lucky it happened early.”

But Fogerty is still trying. Berkeley remains his base; it is where he’s always recorded, right up to the ominous, brand-new “Run through the Jungle”-like single, “You Got the Magic,” his first all-out attempt at AM success since “Sweet Hitch-Hiker.” “All this business about artists being ashamed of commercial success…” Fogerty shrugs. “What is that?” And for once Fantasy agrees. “No doubt again it,” Ralph Kaffel says. “Fogerty is back with this song.”

Fogerty will be touring again, too, after he records an album in the late spring. “Just me and a small band of guys that won’t look at all like it’s just another gig. I’ll keep it simple, too. Just like the dance the other night. To me a synthesizer is not something to boogie to.”

Fogerty first came to Troy a year and a half ago. Not long after that, he bought land. The townspeople welcomed “the guy that wrote ‘Proud Mary'” like a long-lost son. Even the town jukebox, once all country, now sports every Creedence single.

He fits right in. “Sometimes,” he says, “I think I was meant to be a redneck. Not that the people here are rednecks, but… you know what I mean. It’s great therapy here.”

“Hey John!” yells a Troy local from his passing truck. “When you gonna be leavin’ us?”

“Looks like Saturday morning,” Fogerty shouts back. “I got some music to make.”

“Well, now,” comes the reply, “don’t you forget to send a record for the jukebox.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #212 – Cameron Crowe – May 6, 1976