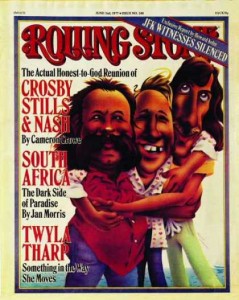

Rolling Stone #240: Crosby, Stills & Nash

The Actual, Honest-to-God Reunion of Crosby, Stills & Nash

There are only two cars on Arthur Godfrey Road this early morning in Miami Beach. One, a Toyota, is full of punks looking for a party. They spot a rented Chevrolet carrying three men, older and looking rumpled in an eerie way. The Toyota pulls up alongside with a honk.

No reaction. Down roll the windows. It’s five in the morning and an Aerosmith tape is blasting out of the Toyota. The guy behind the wheel leans out and yells: “Hey, let’s go find some chicks!”

Then it registers. What? The driver nearly careens into a divider as he tries for a better look. It’s-

The three men ignore him. The Chevy pulls off on Pine Tree Drive and slowly pulls into the driveway of a miniature villa. Just as the driver is about to shut off the ignition, a familiar song – “Woodstock” – by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young-comes on the radio. The driver cranks it up, and all three begin to sing along.

“What a rush,” whoops Graham Nash. He remembers his harmony line perfectly.

Stephen Stills is grinning broadly. His missing tooth is in full view.

David Crosby, the driver, stares straight ahead. “Yeah, we were definitely hot,” he says, turning off the ignition at the song’s end. “That love, peace and granola shit went over real big, didn’t it?”

They laugh, grab their guitars out of the trunk and head inside. After five weeks of recording and living together in this spacious house, life has taken on a cuckoo-clockwork domesticity: up at 5 p.m., dinner at 6, Walter Cronkite at 6:30, recording studio at 8, then home for a sunrise breakfast.

“I’m just gonna put my guitar in my room,” says Stills brightly. He bounds up the stairs. “Meet you guys in the kitchen for a nightcap. Save some Shredded Wheat for me….”

So Crosby, Stills and Nash ? CSN – are back together. It’s 1977, eight years since their first and only album became a rallying point for a budding Woodstock generation. But now, Richard Nixon is out of office, the war is over, marijuana is slowly being “decriminalized” and a Democrat is in the White House. Rock music is bigger business than ever, and artists like Peter Frampton and Fleetwood Mac easily outsell the entire CSN catalog (with or without Neil Young) with a single album.

And yet, Young is back with his band, Crazy Horse, and CSN are back in the studio. Another turn around the wheel….

There was a time in late 1970, with Deja Vu at its peak, when CSNY were just about the American Beatles. The four of them had clear and separate, slightly adversary identities: Crosby, the former Byrd, the political voice, the California dreamer; Nash, the Briton, the former Hollie, the spiritually hungry searcher; Stills, the guitar hero from Buffalo Springfield; and Young, the brooding dark horse from Canada. They were, at once, steeped in mystique and still the guys next door.

“They always had that Judy Garland, tragic American hero aura about them,” a former business associate remembers. “It’s still going on. Were they strong enough to survive? Would they kill each other? Did they really like their audience? Were they leaders? Was it all for the bucks? Would they fall apart before reaching the top?”

In the end, they did fall apart. In 1970, after less than two years, CSNY shattered into four directions several months after recording the single “Ohio,” backed, ironically, with “Find the Cost of Freedom.” With the exception of a summer-long reunion for a tour in 1974, they never got together again. Apart and in partial combinations, their projects were mostly disappointing. But every year or so there was a tease. At least three times they announced attempts to record another CSNY studio album, but each one collapsed in bitterness. In their place, bands like the Eagles, whose members once idolized them, emerged.

And then, two months ago, I got a phone call and invitation from Crosby: “We’re doin’ it, man. It’s CSN, just us this time, and it’s coming out. C’mon down and have a listen.” A plane flight later, I learned that he was right. For the first time since those nights in 1969, Crosby, Stills and Nash are in harmony. Only one question: does anybody out there still care?

“Anything you want to know/Just ask me/I’m the world’s most opinionated man” – “Anything at All” by David Crosby

David Crosby is not quite ready for that one. He thinks about it for close to a minute, an uncommon silence for a man who calls himself “Ol’ Motormouth.” It is the next morning and Crosby is finishing off a snack of bacon and eggs. He dabs away the yolky residue caught in his waterfall moustache and smiles. “Sure, we may have blown it,” he eventually admits. “But what constitutes blowing it? Not playing the game? I don’t see any rules, anyway….Overall, I don’t regret anything. I’m here and there’s music…and it’s being released. And I’m making it. Sure, the specific things I regret. Pieces of music that were never made or never came out…but I’m glad that we were smitten in the face with reality again and again. If we’d had to knock those corners off each other rather than just bounding down a couple of staircases of life, I think there might have been too much scar tissue between us.

It’s hard to keep from gagging on Crosby’s constant paeans to The Music, but he is sincere. Music, by choice, is his “entire being…with sex a very strong second.” He lives his life from album to album and from tour to tour, rarely allowing himself any time home alone. At night, he is often in the studios, either working in his own projects or cheering others on. And he spends his days ruminating over songs, letting petty business matters grow into problems.

Crosby, 35, has gained weight from lack of exercise, and he’s sensitive about it. Propped up against the headboard of his bed, unshaven and wearing baggy cords and an oversized Pendleton shirt, he exudes a grandfatherly benevolence.

In Miami nine months earlier, the last attempt at a CSNY album had left a particularly foul taste in his mouth. Yet Crosby is back for more. “I look at it this way,” he once said. “Suppose you’re crawling through the desert, you haven’t had a drink in days, you’re parched, dehydrating. And then you remember where you once drank from this deep, crystal blue oasis. Would you go back there or what?”

Boats drift along the canal outside, and Crosby smiles wistfully at the view. He begins to stare. I wonder if he looks back at himself and sees naiveté. “You always do,” he says with a world-weary sigh. “My whole ‘Wooden Ships,’ wanting-to-sail-forever fantasy was bullshit. Where do you get off leaving the rest of humanity behind, even in your mind?….You live, you learn.”

Crosby and Nash have remained close friends through the years. So all they needed to accomplish a CSN reunion was Stephen Stills. It is strange to hear Crosby answering for Stills’ celebrated inconsistency. But he does so, and vigorously. “I’m not gonna hype him,” he begins. “He’s not a saint. He didn’t suddenly change. The thing is…you don’t get it for free. You can’t ride on your fucking laurels, it doesn’t work for long.”

Crosby doesn’t like to go into specifics about personality differences with Stills, and says only: “He and I used to go nose to nose about once every 15 minutes. And we haven’t gone nose to nose once. Nothing. It’s either amazing grace or great luck, but it’s working…”

He leans forward and speaks in a stage whisper, overenunciating every word: “His chemistry is altered because he is not drink-ing ….That cat, believe me, when he’s heavy into the sauce, he doesn’t have the chops, the attention span, the patience…he derails, he goes on trips…he can’t make the music. But when he feels supported and when it’s called up out of him, bullshit on the people that think he can’t do it. I’m proud to say that it happened to be us that could call it up out of him again. He says it, too.”

They assume that Neil Young knows exactly what they’re up to in Miami, using two months of studio time that Young himself wanted to book. But there has been no communication. He is spoken of in friendly but distant terms. Young views CSNY as an occasional marker in his own career, but CSNY comes first for the others. “I love singing with those guys,” he said in 1975, “but CSNY tends to get too big. Too many people attach too much importance to them. I enjoy being able to visit, but I want to avoid people thinking, ‘Oh, there’s Neil Young from CSNY.'”

“At this point,” Crosby says, “I don’t know how to deal with my relationship to Neil at all. The last time the four of us were together, the psychic balance in the room, the level of trust, love or friendship was like”…Crosby whistles…”real strange.”

That was last May, and the room was the very same Criteria Sound Studios. Recording sessions by the Stills-Young Band had reached an impasse. Young called Crosby to see about giving CSNY another shot. Crosby and Nash, close to finishing their own album, Whistling down the Wire, in Los Angeles, flew to Miami Beach. It was a disastrous move. Besides a lack of material and some disagreement over the approach, there were rapidly approaching deadlines. A summer-long Stills-Young Band tour was scheduled to begin in June, and Crosby and Nash were already late delivering their own album. They finally had to rush back to L.A. to wrap it up, leaving Stills and Young to work on the CSNY album until they returned. Instead, the album reverted to a Stills-Young project. Crosby and Nash were not invited back to Florida, and their vocals were wiped off the tracks to make room for others.

Crosby was livid at the time. “I have nothing but contempt for those two,” he said then. “I refuse to be on call for them any longer.” Now, he can rationalize the incident: “Everything was wrong. I wish to fuck, man, that I had not felt so long an enmity for those cats over that.”

In the end, the Stills-Young tour fell apart after a month. Crosby and Nash played throughout the summer, and the incredible irony occurred: the two harmony singers, the leftover pieces of the old group, outsold the Stills-Young album (Long May You Run).

The phone rings and Crosby snaps it up, as he usually does whenever a ringing telephone is within reach. It’s John Hartmann, one of Crosby and Nash’s managers. “Yeah?…I’m just shooting my mouth off….Well, how’s things on that battlefront?…What did the Turk say?…Did you call the Russian? What did he say?…Well, play it for him. Our end is together….”

It is an easily breakable code since I know that CSN, still signed to Atlantic Records (where Ahmet Ertegun, “the Turk,” is chairman), want to find out whether or not there might be another company that wants to buy them out, like, maybe, the only label that could afford them, CBS Records (whose president is Walter Yetnikov, “the Russian”). Crosby hangs up.

“We’re having a huge business duke-out at the moment,” he says, “which is what all that is about. You know, we’re spread out all over the record business. At present we’re on three different companies [Crosby and Nash are on ABC. Stills is still with CBS as a solo artist]. It’s weird that it should be fought over like 40 pieces of silver. But we know what it is in terms of its commercial worth. We know what happens when you make sounds as unusual and completely different from everything else as this does.

“If all somebody has to relate to, in terms of what’s gonna come out of this, is Whistling down the Wire and the Stills-Young Band, they’re in for a monster surprise.”

A striking blond woman, the cook and part owner of the agency that rented the house, pokes her head in the door and announces dinner. And so begins the prestudio ritual.

Downstairs, a spectacular spread is being attacked by Stills and Nash, by Joel Bernstein, their photographer of seven years, and by their young crew of three. Dinner is over in ten minutes; then they watch CBS news for their nightly crash course on the real world. CSN like Jimmy Carter. They had talked about announcing their reunion by singing “The Star Spangled Banner” at his Inaugural Ball. Crosby, oddly enough, is the biggest fan of the president. The same man who in the past had proclaimed himself “ashamed to be an American” would gladly accept an invitation to the White House. “The Constitution is still strong enough to beat Richard Nixon,” he says. “Bottom line, man: dude lost.” As for Carter: “I feel that this guy is so intelligent that he knows how to be human and accessible and real. It’s sheer genius….”

After Cronkite, they zip down to the studio. As he walks in, Crosby triumphantly claps his hands. “All right,” he booms, “We’re gonna finish the album tonight.”

He has said the same thing every night at the same time for the last five weeks.

The album will be called simply CSN. Outside of keyboardist Craig Doerge, drummer Joe Vitale, bassist George “Chocolate” Perry and one track with drummer Russ Kunkel, the album is all their own work. It was coproduced by Ron and Howard Albert, the earnest young brothers who have had a hand in nearly everything that’s come out of the Miami studios since Brook Benton’s “Rainy Night in Georgia” in 1970. The Alberts are quick, thorough, and determined to make a Seventies CSN album. They are succeeding.

Tonight, with the instrumental tracks finished, the moment of truth has arrived-after four days of rehearsal, it’s time to record vocals. They’ve been singing all night, carefully bearing down to capture the harmonies.

Stephen Stills stands in the middle of the carrot-colored studio B-the same gauche room where Eric Clapton recorded “Layla” and James Brown did “I Feel Good”-and madly smokes himself into a Marlboro cloud. He is on the crest of finishing a difficult, overdubbed vocal part on “Anything Crosby’s At All.” Graham Nash watches from Stills’ left. Crosby is lying on the floor, staring at the ceiling and calling out suggestions. “Hey,” he gripes. “I keep hearing the Average White Band getting’ down in the next room.”

Stills ignores the gentle thumping and continues his last remaining line several times without much success. Ron Albert flicks down the intercom switch. “You’re flat, Stephen.”

“I’ve made a whole career out of singing flat,” replies Stills. He returns to the line, tries more times, and then gets it perfect.

The Alberts, who’ve worked on most of Stills’ solo projects, begin to talk between themselves. They don’t know I’m sitting on a couch below their control board.

“Do you believe this?” asks Howard. “I don’t believe this.”

Ron chuckles. “Did you ever think we’d see the day when Stills worked this hard on a record? Is this real?”

“He wasn’t this on top of it for the first Manassas, even, was he? That was a great album…the last classic record he made.

Stills walks in and the musing immediately stops. He plops on a stool between the two brothers to hear his playback. “You know,” Stills confesses out of the blue, “I’ve been getting away with murder. I think back on my solo albums, and there’s some good stuff here and there…but it’s mostly garbage, isn’t it?”

I can see the Alberts’ reflection in the studio window as they turn to each other. “Pretty much, Stephen,” Ron says agreeably.

Stills begins to laugh heartily, something his friends say he’s only recently capable of, until Crosby, still on his back in the next room, roars over the monitor: “All I wanna know is this – are we gonna have to give the AWB credit for percussion of this album?” Everyone cracks up.

They decide to knock off a bit and play me the 12 album tracks, chosen from a possible 17. All three stand and sing their unrecorded parts with the tape.

Here’s the Rundown: “Shadow Captain” – Craig Doerge wrote the music, Crosby the words…instantly recognizable, streamlined CSN, clear and strong. “See the Changes” – classic three-part harmonies huddled around an acoustic guitar; Stills wrote and sang lead. “Carried Away” – a beautifully stark Nash piano song with interwoven harmonies. “Fair Game” – Cubano Stills, well sung and brandishing a killer guitar solo. “Anything At All” – a deeply felt Crosby composition about a man who will answer any question. “Cathedral” – Nash started this song on his 33rd birthday after wandering into Winchester Cathedral on acid. Intense.

Side two: “Dark Star” – another great Stills song, overtly commercial and made for summer. “Just a Song Before I Go” – a breezy love song from Nash (whispered Crosby: “The girls are gonna fall in love with him all over again. I hate it.”). “Run from Tears – the best electric Stills in years, with chilling vocals and a fiercely real lyric about keeping his head above water. “Cold Rain” – written by Nash during the sessions after returning from his ailing mother’s bedside in England. Gray and moody. “In my Dreams” – Crosby stretches out with a sinuous acoustic tune. “I Give You Give Blind” – more excellent electric Stills. A sophisticated, assertive closing note.

“I’m just hoping that it…just slays everybody. I really want it so bad, you know. For me, It’s kind of half out of responsibility to show the kids and half ‘I’ll show ’em…thought we were washed up, didja?'”

Stephan Stills is a man with a reputation for being fucked up, coked out and/or fried to the gills. He concedes that he has done plenty to deserve that stigma, but, against incredible odds, he has survived. And his survival is one of the most important factors in the successful reunion of CSN.

To look at Stills today, at 32, you see a much different person than the gaunt, eager young man who confessed to the audience at Woodstock that he was “scared shitless.” His face has spread out and hardened since then. He often wears glasses. He is smaller and huskier than you might expect.

“Right now, I’m a cripple,” Stills says, taking a seat in the closet-sized mastering room at Criteria. “I’ve been sick through this whole thing. Then my back went…God knows what did that. It’s probably all psychosomatic.” He gets up to grab an ashtray and bangs his head on a tape machine. “Oh-no. My body is rebelling. But…I’ve been working solid for six months. You know, the light is at the end of the tunnel…I’m just hoping my poor body holds up long enough to get to it.”

Stills is just now recovering from a particularly devastating stretch of his life that began with the release of Long May You Run last August. First Neil Young dropped off the summer tour of the Stills-Young Band after only a month, allegedly because of a sore throat. Others have suggested Young was bored. Says Stills: “All I know is that he turned left at Greensboro…”

I remember calling Stills on the road in Atlanta, the next stop after Greensboro, for some backup questions on a piece I was writing. I didn’t know the roof had just fallen in. Stills, who was in a hotel bar, grunted something about wanting to be left alone and brusquely explained that Neil had disappeared and left him a goodbye telegram saying, “Funny how some things that start spontaneously, end spontaneously…”

“I have no answers for you,” Stills had said then. “I have no future.” Chills. Two weeks later, still gamely making up on some cancelled dates without Young, Stills’ wife Veronica Sanson, a singer/songwriter, filed for divorce. Stills ordered everything packed and moved out of his home near Boulder, Colorado, where the marriage started. He now lives in L.A. and has not been back to Colorado since.

“Lenny Bruce was right,” says Stills. “When you get divorced, the longer you’ve been married, the longer you throw up. I’m not over it yet.

“I went crazy for two weeks, you know, but I picked myself up off the ground and went to the studio. I guess there wasn’t anyplace else to put my energy. It was like the coyote in the Roadrunner cartoons, just after he goes off the cliff…suspended in midair, scrambling to get back on the cliff.”

I am drowning/And I am fighting./Something special/Is in me dying… — “Run From Tears” by Stephen Stills

Stills started writing his best songs in many years, all of them passionately autobiographical. He also started to think about his still bitter friends, Graham Nash and David Crosby. Stills humbly showed up backstage, uninvited, at a Crosby/Nash show at the Greek Theatre in L.A.

Nash: “I hugged him. And it amazed me. ‘Cause I realized in the middle of the hug that the last time we’d met he’d wiped some very valuable work of David’s and mine…but it didn’t’ matter. We’re all incredibly changeable people, God knows, and Stephen had come with his hat in his hand. So fuck it. I hugged him.”

Crosby: “After that last debacle, I looked at Nash like he’d lost his total mind. I thought he was just out of his fucking tree. Completely. Then I hugged Stills too…the pencil-neck wimp.”

Stills joined in for the last encore number, “Teach Your Children,” and his bruised ego soaked up the tumultuous reception. Afterward, Stills and Nash, long the weakest link in CSNY, went out and got drunk. “He was really the Stephen that I had always hoped I’d see back again. I piled him back into his room at 4 a.m.” Crosby and Nash continued with the fall tour, as did Stephen with a series of solo acoustic concerts, but the reunion was already on their minds.

They met up in December, recorded some basics at the Record Plant in Los Angeles, then flew to Miami to finish the album. The key to the sudden harmony? “Everybody is a lot less sensitive,” Stills replies. “We have a common, realized interest. We took a tremendous gamble the first time with Nash quitting the Hollies and everything…Music From Big Pink was out and all that…we really had to be good. And we were. We’re up against the same thing now. We’re taking a gamble with our reputations…the pressure’s on.”

I tell Stephen there are some who point to his lack of drinking as a major plus factor. He laughs tentatively. “I mean,” he says, “I’ve always been a cheap drunk.” He looks sheepish. “I’ve spent a lot of time drinking Scotch onstage and stuff…I just quit. It was seriously interfering with my ability to perform, to sing in tune. It made me braver, but I just wasn’t pulling it off. I sat in with the Average White Band, man, the other night and I had three gulps of Scotch and I was just blind. Just…completely…on…the roof. I have definitely quit.”

Directly after the CSN project, Stills will finish another solo album. He asked Graham Nash to produce. After that, he says, he will concentrate on CSN indefinitely. He does not miss another guitarist, particularly Neil Young.

“The album we did was a nice avant-garde piece. I can’t see why it didn’t do better. We were a little offhand about it. There were some special songs in there that we could have treated…a little more special.

“Neil is Neil and CSN is CSN. That has always been true. I think Neil does”…Stills sighs…”what the hell he wants, you know. And he puts as much energy into it as…he wants. That can be 100 percent or it can be 75 percent…and he really doesn’t give a damn. My relationship with Neil is certainly not severed. I mean, none of us are into closing doors.”

There is always the specter of money looming over such reunions as this, just as it did when CSNY re-formed in ’74 for an album…and a summer tour. The album never happened…but the question begs to be asked: is it for the money?

“It isn’t,” Stills declares. He is, naturally, offended. “We’re not broke. We’ve all got money coming in from other sources. But we’re gonna make a lot of money, nice bucks. And we’re also gonna deliver. We gotta…and we’re gonna. And that supersedes the money and everything…I mean, there’s not one disco track on the album. How could it be for the money?”

I thank Stills for his time and venture to tell him that there are people who will be very surprised by his strong showing on the CSN album.

“Hey, don’t ever count this boy out,” he advises. “Don’t ever count me out.”

Stills jumps to his feet for a dramatic exit on that line. And bumps his head on the tape machine again.

In the past few years Graham Nash has developed the public image of an exasperated Richard Benjamin struggling to reunite the Sunshine Boys. In the aftermath of the various breakups, it is he who has been left most dejected, wondering why everybody can’t just act like adults. In the span of their history, Nash has never initiated any of their notorious blowouts.

Graham is the quintessential gentleman, able to make instant and lasting friends. A promo man he just met can become “my friend Bill,” a fan who wants to talk about “Lady of the Island” will not be ignored. He is good-humored, sensible, warm and open, yet very private.

This morning he sits on the expansive backyard lawn, next to the rushing canal, chipping away at an alabaster sculpture. From 20 yards away, I recognize it – an amazing bust of David Crosby – and ask why he would want to spend an excruciating amount of time sculpting the face of someone he has seen practically every day for the past eight years. Nash says he couldn’t help it. The rock just looked like Crosby.

Nash is wearing tiny antique goggles. He throws his head back into the sunlight. “I feel fine,” he says. “Some of the rushes I remember from that first album – when we hit a vocal chord or a vocal blend – I’ve had the same rushes here for the first time since. That’s why I’m so peaceful about it all.”

Last night, after first hearing the Eagles’ “Hotel California,” Nash had lifted a defiant middle finger to the line, “We haven’t seen that spirit here/Since 1969.”

Nash probably has the keenest sense of the group as something more than an old spirit. In recent years he’s been responsible for compiling the Four Way Street and So Far albums, putting together set lists for their concerts and even sequencing the latest album. And he is a brilliant arranger and producer.

But he has loftier goals in life, you sense, than writing “Our House.” “I tend to get a little into the importance of what I’m doing, because I’m so focused on it. I have to maintain the ability to step outside and realize that all this doesn’t mean shit to…that palm tree.” He would rather see his friend and inspiration, Jacques Cousteau, on the cover of Rolling Stone.

Nash has gone through several complete life changes since growing up in Manchester, England. And he is certainly capable of several more. When he was 15, his father bought an antique camera from a friend. The camera turned out to be stolen and when the police came around, William Nash refused to divulge any information. He went to jail for a year and his only son, Graham, went to work to support his mother and two sisters. Graham took odd jobs in a wool factory, a brewery and a post office to keep the family afloat. He soon made enough money from singing and playing guitar with a buddy, Allan Clarke. Together they became the nucleus of the Hollies. Nash Sr. emerged from prison weak from pneumonia and broken in spirit. He died a year later while Graham was on tour in Sweden. Graham’s chartered plane arrived a few hours too late. Missing a farewell to his father, he says, is his only regret in life.

The Hollies were a huge success. They developed a rigid, faultless formula that was something of a mixed blessing. By 1968 Nash had broken out of the mold and was writing “Lady of the Island,” “Marrakesh Express” and “Right Between the Eyes,” songs the other Hollies vetoed. When the group reached L.A. for a run at the Whiskey A Go Go, Graham made friends with Cass Elliott, who brought him to Joni Mitchell’s Laurel Canyon home. The rest has become well-drilled history. That night Nash met Crosby and Stills and sang with them. He promptly discarded a budding middle-class existence-the O Lucky Man syndrome as Crosby calls it – with 100 in his pocket. His momentous departure from the Hollies is still remembered in England: “Every time I go back there,” says Nash, “I still feel this strange edge….”

I guess I’m taking a chance, moving out here to L.A., leaving my money in England and singing with David and Stephen. But it’s what I want. At least it is for now. — Graham Nash, Hit Parader, September 1969.

We take a little break. Someone has brought wine and cheese and fruit and deli. Graham and Joni are getting silly together. Stephen is muttering about getting back to work. David is slumped on the couch, cuddling a bottle of wine. He closes his eyes and his mouth curls into a smile. “I’ve never had so much fun making an album in my entire life”

— Hit Parader, September 1969

By the time CSNY, Crosby, Stills and Nash – with Neil Young – reached the studio in 1970 for Deja Vu, they were the American group. But the sunshine and light of the first album had dissipated. “When it’s that enormous, all of the chemistry is heated up,” says Crosby. “Everything takes place faster and bigger…your own emotions included. It went downhill as a relationship, and it’s as equally divided a fault as I can think of…all four of us blew it. Everybody got paranoid about each other. We were all independent enough motherfuckers to go and do it on our own. We all thought we could.”

“It was an incredibly painful album,” says Graham. “The first one, we were all madly in love. The second, we weren’t even close.” The sessions were moody, sullen marathons and the vibe even carried over to their subsequent tour. Stills was fired in Chicago, reinstated two days later, but when the tour ended, they scattered.

An attempt to reunite on record in ’73 got as far as a finished package and title, Human Highway. They went to Hawaii to rehearse, came back and ran out of impetus. The cover photo, taken at sunset on their last day in the islands, tells it all – a clear portrait of four tanned men, all living in completely separate worlds. The print is now tacked up on Neil Young’s bedroom wall at his ranch.

Another stab at CSNY happened in Sausalito after the summer ’74 tour. It ended after several weeks, as a result of momentous argument between Nash and Stills over a single harmony note. Neil Young left the studio and never returned. “It was an incredible thing to have happen,” says Nash. “I didn’t quite know how to deal with that for a long time. But it served its purpose by pushing David and me out onto the crossroads.”

They were an obvious match, Crosby and Nash. They had already toured and made an album together, but this was a matter of an entire career. The turning point was an unexpected call from James Taylor, who wanted them to sing on his album Gorilla. They accepted (Nash: “We’re musical junkies, we’ll sing for anybody”) and in the course of one high, musical evening, recorded Taylor’s “Mexico” and “Lighthouse.” Graham and David, then living in the Chateau Marmont residential hotel, floated around L.A. in a haze for days, singing the chorus from “Mexico.” They had proved to themselves that they were more than retread folkies.

Crosby and Nash – working without a manager at the time – rode the blast of confidence into a deal with ABC Records and an album, Wind on the Water, assisted by Carole King and Taylor. A successful tour was followed by another album, then the abortive trip to Miami Beach. And now this.

“Ah, yes,” Nash notes. “Here we are in the years, as they say.” He chips away on his sculpture of Crosby. “Back on bended knees.”

No, Nash decides, he would not take it all back. “It was so strange going back to Manchester this time,” he says. “I still see the exact same faces and ruddy complexions and the people scurrying by…and they’ll never change. But for a few good fortunes, I might still be there.” He shudders. “No, I would not go back.”

I mention the Rolling Stone interview in which John Lennon claimed he’d rather have been a fisherman in Surrey. A voice from behind responds: “Crap he would.” It’s Crosby, rubbing his eyes in the sunlight. “He just damn well wouldn’t…he wouldn’t have settled for it, because he’s one of the ones that left home. Like us. There’s always some of them that leave home…They’re too dissatisfied or restless or horny or something. And we’re the ones that left. You’re one of ’em. He’s one of ’em, or else he’d still be in the wool factory. I’m one of ’em, or else I’d be back in Santa Barbara now, working for Washburn Chevrolet.

“As far as I’m concerned,” says Crosby, “the best thing for me to think about Neil Young is: later. Because if he showed up, right now, he’d just weird it out. He can’t do the kind of painstaking work on vocals that we’re doing right now. He doesn’t believe in it. He can’t even sit there while you do it. And he’s proven that.” Crosby chipmunk giggles. “He’d rather clunk around with that garbanzo band of his….

Why do you ride that Crazy Horse/Inquires the Shadow with little remorse… — From the unreleased song “Homestead” by Neil Young

Young has gone on record as saying he made a commercial, technically perfect album in Harvest and “got it out of my system.”

“That’s just an excuse to not have to do it,” Crosby retorts. “That’s a shuck. He makes stuff, man, that if you listen to it the right way, it has moments of such startling art in it that you can be knocked out by it. But he could take his music much farther. He’s also got this massive anti-God thing. He hates being so big and he tries to demystify himself by being funky. In music and in life. I’ve argued all these things with him, to his face. He laughs. He loves it. Bottom line? Neil’s the most fascinating person I’ve ever met.”

A laborious detailing of all the various unreleased CSNY tracks now sitting in the can follows, and Crosby begrudgingly admits each one’s existence after much arguing. After several hours, we figure there is at least one great CSNY album among the tape archives of each member.

Nash, who has said little, interrupts as he senses yet another argument looming. “This is getting boring,” he declares, and a few minutes later he grabs his sculpture and walks back inside. Not quite realizing the reason for Nash’s departure, Crosby follows him. I follow Crosby. The conversation resumes in Nash’s room.

“Please,” Nash pleads, “don’t drive me out of my room. I came in here to escape you all.”

“Sorry,” Crosby says, “it’s his fault. He didn’t ask my favorite questions – what I have to say to the 15-year-old girls of America, what kind of weird sex trips I’m into, where I buy my clothes, nothing.”

Nash remains serious. “None of the stuff we’ve talked about has been important…it’s just part of a vast complex of much more important things. And we’re a small part. Right now, ’cause we’re all in this house, it’s a large part of our lives, but if you take it from the point of view of the guy next door…he doesn’t give a fuck, you know.”

Back in my room, it’s unnerving to think about this, staring at six hours of tape. Sure, it’s historically valid to gather all the details, all the intricacies of each split, but…in the end, isn’t the reality that CSNY are four guys who couldn’t manage to sit down in one room long enough to make the very music they claim they live for? In ten years, is that the irresponsible legacy they intend to leave?

I take that last question back to Nash’s room. He and Crosby are engrossed in a Jacques Cousteau TV special. Crosby looks up, sees me and the tape recorder back again, and beckons. “What’s your last big question of Doom and Destiny?

It is a difficult question to phrase, and it comes out as: “Look at the fans who loved Crosby, Stills and Nash and Deja Vu and thought they were some of the best LPs in their collections. They’ve followed you through all the breakups, the false alarms, the canceled tours and partial reunions, and there still hasn’t been another album. Might they not be tired of it all? After all, there’s still the new Pink Floyd album….”

Silently, Crosby continues to watch television. “Look at the geese! Look at the geese!” he says. Another minute. “I don’t know. It’ll depend on how much music was the issue or the fantasy characters that the media tried to create. If it was the music that moved them, I’m sure that the on-again, off-again rest of it isn’t that relevant.

“If, on the other hand, they were more concerned with the psychodrama of the group trips…and flashed by the bullshit star thing, then maybe they’ve moved on from that to something else, like gas stations and Parcheesi.

“Overall, you can’t look at your life with regret…and do shit. So no, I don’t regret. I…I look for my car keys and go to the studio.” Crosby laughs and dangles the car keys from his finger.

Nash is troubled by the lack of sensitivity in his answer. “I agree, David,” he says. “I totally concur, I was just thinking about the crux of the question, which was – do we think we were silly. In a certain way I think we were very silly…in not growing up quite so fast.

Joel Bernstein, their photographer and guitar-tuner of seven years, is also in the room and adds: “This all must seem childish to someone on the outside.”

“Fuck ’em,” says Crosby. “I can’t live my life for them. I’m telling you what the truth is.”

“It’s just,” Bernstein resumes, “if you put yourself in the fans’ place, you can maybe see how their attitude toward you guys may have changed.”

Nash: “It’s possible.”

Crosby: “Okay…that’s very distant from me, okay, but I’ll respond. It is fringe. The only real consideration that anybody ever had to think about was whether or not the music got to them. Anybody that’s into it to the level of following it as a psychodrama is fringe to me.

Bernstein: “I’m not talking about those people. I’m talking about your fans…the people who buy your records.”

Nash: “Well, we’re taking care of things. We’re doing this album….”

Crosby: “I’m talking about all the fans, then. Everybody. Merely being conscious of them and what they care about and how they feel about whether or not we should or should not be playing is counterproductive to making art. So fuck you, number one.”

Bernstein: “That’s contrary to your criticism of Neil and his craft.”

Crosby: “I’m not talking about how you make the music. I’m talking why. I’m desperately concerned with communication. Just let me finish. What went down is that…we tried over and over again because we wanted to do the music. We didn’t try because we felt a pressure or need to satisfy these other people’s predilections for one thing or another – fuck them. They can’t help me or hinder me from making that magical moment on tape. Only. my own personal love or hatred or feeling for…[the blood rushes to Crosby’s face and he begins to bellow]…Neil, Stephen and Graham has anything to do with it. Only. Nothing else. So their whole entire consciousness – whether they liked it, didn’t like it…thought it was cool, hip, chicken, fucks…nothing. It’s all totally extraneous to me.”

Nash stops chipping on Crosby’s bust and looks up curiously. And it’s totally, totally intimidating of the one fucking chance you got to break through and make this happen. The consciousness of that bullshit, the history and psychodrama and what everybody else is thinking about it is exactly why the four of us walked in to the room the last time and…blew it! Because we were dragging that baggage. Can you dig it? Fuck you, number two!

Crosby catches his breath. “That’s why we keep looking at each other and saying, ‘No history, next subject.’ That’s not a joke. That’s trying to keep from drowning. Excuse me for getting a little intense. But it’s our music…that’s why we make it for ourselves.

“People are gonna listen to this, I know, and wonder how ‘right on’ it will be. Well, CSNY and CSN was a rallying point because it was just a shared experience. Like Easy Rider was. Not because of anything we planned…we’re not leaders. There isn’t a leader in us. But if I started to think about all those people and what’s gonna satisfy each and every one of them, how far am I gonna get?”

Nash: “He understands that. You explained to him about cheese. He thinks he tried to ask you about bacon.”

“No,” Crosby states flatly. “Suck cheese, English” For a moment, he sounds and looks like Larry Mundello, the easily bruised neighborhood kid from the old Leave It to Beaver TV show. “No, I nailed it.”

Howard Albert had stumbled across someone pissing in the bushes outside as he walked into the studio that night. A few minutes later Albert had found out who he was when a wiry, bearded man in Levi’s and checked shirt wandered in the front door.

“Was that you out there?” Albert asked.

“Sure, man,” he said with a crooked smirk. “Jus’ out there takin’ a leak on a warm evening.”

Neil Young had come to see Crosby, Stills and Nash. He walked into the control room unannounced and four men lunged to hug one another. “Big problem with CSNY,” Young cracked. “Too much hugging.” To see them all together in one dimly lit room was an incredible sight – like watching four big old gray timber wolves circling.

A tape of CSN – now completed and needing only final mixing – was slipped on and, with the opening notes of “Shadow Captain” booming over the speakers, Neil stared down in bemused satisfaction. When the first three-part vocals filled in, he looked up and smiled broadly. “It’s nice to hear that.” “Real good to hear it again.” Young listened on with warm enthusiasm. After the last track on side one, while the second was being hurriedly readied, he insisted on a break.

“Hey guys, c’mon,” said Young. “You spend eight years making your second album and you want to get it over with in 45 minutes…

“Sheesh.”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #240 – Cameron Crowe – June 2, 1977