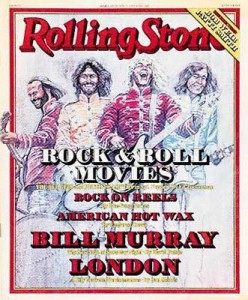

Rolling Stone #263: American Hot Wax

American Hot Wax: Freed at Last

It is a chilly morning and only slightly warmer inside the cavernous Paramount sound stage, where the last frenzied week of filming American Hot Wax was has just began. “Turn that heat down, willya,” an assistant director barks at the janitor. “We gotta lot of work to do. Let’s just keep everybody alert.”

There already had been more than a few delays over the last six weeks, and producer Art Linson (Car Wash) is quite aware of the oncoming crush of rock films such as Sgt. Pepper, FM and Thank God It’s Friday. But today he received a tip from the higher-ups at Paramount: if his film – the story of rock & roll’s early years and the legendary disc jockey who popularized the phrase, Alan Freed – could be finished, say, yesterday, there is the slightest chance it could get an early release, before any of the competition. Director Floyd Mutrux and cinematography chief William Fraker are working at full throttle to set up these last scenes swiftly and exactly. No time for second chances.

The scene being filmed this morning is a particularly hectic moment in the life of Alan Freed, portrayed by actor/musician Tim McIntire. Freed strides down a hallway and into his office. Every step of the way he is accosted by someone pushing a single, hawking an artist. At his side is real-life manager Artie Ripp, cast as Freed’s manager and talent scout.

Suddenly, a hand grabs my arm. “You’re gonna be an engineer,” says Art Linson, dragging me into the starkly lit set, down the hallway and into another room. Mutrux and record producer Richard Perry are discussing a scene in which Perry, as George, cuts a hit record with the Planotones, a fictional group. “Here’s our engineer,” proclaims Linson.

Perry explains that engineers were older then. So Linson gets another thunderbolt. “He’ll be the delivery boy!” Nods of agreement. My name will be Gilbert. I am to deliver Chinese food to a Planotones sessions, where Alan Freed presses me into action, singing and clapping with my heroes, the ‘Tones. My line: “Who ordered the shrimp and rice?”

I am whisked off to wardrobe and into the Fifties. The costume designer fits me with ratty tennis shoes, an apron, a T-shirt and a little white hat. He then hands me a package of ketchup. “Just spread a little of this on yourself,” he instructs. “Be here at eight in the morning. Be prepared to spend a couple of days.”

Making a film about Alan Freed was the idea of Linson and screenwriter John Kaye. They took the concept to Paramount executives Don Simpson (vice-president of production) and Michael Eisner (Paramount’s president). “We were very excited by this idea,” says Simpson. “We sent Linson and Kaye off to write a screenplay. And when the script came in, I read it during lunch. Then Eisner took it, shut his door and read it in an hour. Then it went to Barry Diller [the company’s chairman]. We all knew. We said in unison, ‘Shit, we’re gonna make this movie.'”

They found a director with “a rock & roll head” in Floyd Mutrux, the young director Simpson had worked with on Aloha, Bobby and Rose. And they chose actor Tim McIntire, who also fronts a band called Funzone, to play Freed. Laraine Newman, from Saturday Night Live, agreed to portray Teenage Louise, the thinly veiled Carole King character who finds songwriting success thanks to Freed. Others, like Artie Ripp and Richard Perry, are from the real record biz.

The key to being a good actor, one extra tells me the next morning, is learning to eat the commissary food . . . and wait. In that order. What about talent, method?

“C’mon,” he tells me. “Everybody is an actor.”

I spend a large part of the day thinking about this in my trailer. Eventually, I venture out onto the set to see what everyone else does with their one-call time. Some spend it judiciously reading scripts, others sneak a joint, and still more remain totally in character. One of them is Jay Leno, who has a hand in the film’s finest moments. As the driver/go-fer, Leno turns around and asks Alan Freed, in the midst of his battles to save rock & roll in New York, “Is it true? They may take rock & roll away from us?”

“Yeah,” Freed says, surprising himself.

“Where would that put you?”

“Oh, I’d be even.” Then after a meaningful moment to reconsider, he speaks proudly. ‘No, I’d be way ahead.”

I ask Lance Freed, standing quietly at the edge of the set, just how accurate the film is. “It’s eerie sometimes,” says the son of the late Alan Freed. “On the air, my father was a little more up, but in this context, the pressure of the anti-rock & roll element he was up against, it’s perfect. Tim McIntire understands the character. My sister couldn’t believe the mannerisms he captured. It’s a film, of course, but these incidents and my father’s lines, they’re true.”

When producer Linson originally approached Freed on the project, Freed’s reaction was, “Look, I have my step-mother and three brothers and sisters. All I can do is have them vote on it.” The Freed family eventually gave the project their blessing, but stipulated that they would supply the authenticity and the scrapbooks. And, a rarity, all those involved are happy with the final product.

“The reasons my father was busted [in the payola scandal] was not that he was set up,” says Freed. “It’s because he was so fucking in love with the music and he was blind. Nothing else mattered. I think they got it with this film.”

The film is finished two days later, and Mutrux, who had been editing all along, had a rough print in a record nine days.

At American Hot Wax‘ premiere I approach a dazed and weary Floyd Mutrux and ask him what kind of man puts himself through the wringer as he has. “Listen,” he says. “It’s the least I could do for rock & roll.”

And then there’s Gilbert, the delivery boy. Well, that role saw some scissors. But if you look closely and don’t blink, you can see him pass through a scene. Somewhere on the cutting-room floor at Paramount is the reading: “Who ordered the shrimp and rice?” Genius. Authority. Compassion. Take my word for it.

As I leave the premiere, I run into Art Linson. “Did you see yourself?” he asks.

“Yes,” I admit. “I’m going to write about the whole experience.”

Linson acquires a benevolent smile and clasps my arm warmly. “Good,” he says, “I didn’t want you to give up your day job.”

Now another, more sensitive man might be discouraged and begin to doubt his future as the complete entertainer. But not me. Not Gilbert. Wiser, perhaps a bit more resolute, I know that . . . well, I’m even. No. I’m way ahead.

Those are only the films with studio deals set. Bob Dylan’s Renaldo & Clara was distributed independently, and distribution is “being decided at the moment,” according to director Jeff Stein, for The Kids Are Alright, the two-hour movie about the Who that features footage dating back to 1964 and includes their appearance in the Rolling Stones’ never-released Rock & Roll Circus. Stein hopes for a summer release,

Elton John and Rod Stewart have agreed to costar in a comedy about two rock stars who have.a love-hate relationship. John and Stewart, known to have had words with each other, begin shooting in October.

In various stages, rainging from talking to production, are Desperado, based on the Eagles album, in development at Warners, with Ray Stark and the Eagles possibly coproducing; The Rockers, a reggae film starring Burning Spear; The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh, “the first astrological-basketball-musical comedy,” according to producer Gary (Car Wash) Stromberg, with music by Thom Bell; Beatlemania, a film based on the Leber-Krebs Broadway production; Return to the Garden, a love story set against the Woodstock festival (in development at Warners), and sequels to Grease (titled Summer School, without Travolta and Newton-John), and American Graffiti. And Paul Kanter’s Blows against the Empire, a sci-fi epic, is afloat.

Of course, every producer, studio executive and moneybag is being flooded with scripts. “Tons,” says Azoff. Hotel California has drawn thirty-live offers to turn that album into a film. Bill Graham, who has options on two film projects (“Contemporary themes,” he allows, “and they’ll have contemporary music”), gets about ten scripts a month. Allan Carr: “After Tommy, we were given a musical version of Dante’s Inferno, a musical version of Hannibal Crossing the Alps. This has been going on since Ken Russell brought this to the screen, and it hasn’t changed.”

Except that suddenly the musical ideas are being turned into movies. Aside from apparent profitability, few agree on reasons for the surge. To Azoff, aside from bucks, “Music wants to be in movies, movies want to be in music. Right now, everyone is bored; the grass is greener on the other side.” To Bob Zemeckis, director of I Wanna Hold Your Hand, “Movies are much more escapist now. We went through a phase of angry, realistic films. It’s like the old Hollywood is back.” With, of course, a new soundtrack.

Sean Fitzpatrick, creative director of advertising at Columbia Pictures, talks demographics. “We figure if you aren’t reaching the thirteen-to-thirty-four-year-olds, you may as well give up.”

Neil Bogart, president of Casablanca Record and Film- Works and executive producer of Thank God It’s Friday, talks demographics … and disco. “It’s a known fact,” he says, “that the majority of people who go into a movie are between the ages of sixteen and forty, so it’s our recordbuying audience.” He adds: “The music business has passed the motion-picture business in terms of volume. And the disco business has passed both. It’s a $4 billion industry.”

Don Simpson, vice-president of production at Paramount Pictures, also talks demographics, but of a different kind. ‘

Simpson, 35, is a music junkie. As the “resident hippie” at Warner Bros, ten years ago, he pushed, he says, for such projects as Woodstock, Steelyard Blues and Medicine Ball Caravan. Music, he believes, has had a great influence on people thirty-five and under. Simpson, at lunch at St. Germain, talks in almost conspiratorial terms about “us,” the people under thirty-five. He recalls reading in Rolling Stone (RS 242) about how we, the post-World War II baby boom, had become “the demographic bulge.” The bulge exists because we, the love generation, aren’t making many babies and have thereby pushed the median age upward. And, by the power of our numbers, we will maintain more marketing muscle than the middle-aged of previous generations. Combined with what he perceives as the rise of a group of young studio heads, Simpson translates this to movie-making terms and, ultimately, to rock & roll.

He points out that Barry Diller, chairman at Paramount, is thirty-six, and Michael Eisner, the president, thirty-five. Diller and Eisner constantly talk music, says Simpson.

So when American Hot Wax came along, he says,” We went crazy for it,”and pushed it—production was finished five days ahead of its forty-day schedule—so that the film could be released ahead of the expected summer swarm of musical movies. And when Saturday Night Fever was offered, Paramount bit when Robert Stigwood told of the involvement of the Bee Gees. “They knew the Bee Gees,” said Simpson, “so they went after it as if it were The Godfather.”

Now Paramount hopes to attract musicians like Willie Nelson, Jackson Browne and Bruce Springsteen. “Peter Asher is a friend,” says Simpson. “We’d like to do a film with him, using the Southern California music mafia: J.D. Souther, Warren Zevon, Linda Ronstadt, the Eagles and Jackson.”

But at the Hot Wax party, which was being taped by Paramount Pictures’ Hughes Television, we were reminded that the bottom line, whatever the idea, is to sell. And today, studios are better equipped than ever to do that.

Beginning with the party Allan Carr staged for Tommy at a New York subway station, music movies have mastered the use of television as a promotional tool.

Following Carr, the Robert Stigwood Organisation staged a lavish party for Saturday Night Fever that, as Bill Oakes, music coordinator for RSO Films, put it, was “free advertising on prime-time TV.”

Allan Carr, despite his reputation as Holly wood’s newest host with the most, preaches moderation. For other people. “There has to be more on the screen than the promotion around it.” he says, without making direct reference to either the Fever or Hot Wax parties. For his own baby, Grease, he hopes to equal his Tommy party, which, as he says, “was probably the most gigantic two premieres (East and West Coasts) that have happened in the movie industry in twenty years. I’m gonna put on the biggest junior-prom premiere that ever happened.” Coproducer Stigwood, of course, will handle the records. And RSO, in Fever style, has already released a single, an Olivia Newton-John/John Travolta duet, three months in advance of the film. The album will be out. in April, and three more singles will be timed with the film’s opening in 800 theaters in June.

The Sgt. Pepper soundtrack (on RSO) also will be out in early June. There will be a TV show; Universal TV shot the making of the movie. And there will be a large premiere at the L.A. Amphitheatre in July.

Neil Bogart will not, of course, be outdone. For the Casablanca Record and FilmWorks-Motown film, Thank God It’s Friday, the cast of TGIF, along with Bogart, will appear on the Merv Griffin Show for two days, a week before the film opens at the end of May. Griffin will help stage a dance contest with finalists from eight different cities. Bogart hopes to get such hoofers as Fred Astaire and John Travolta as judges.

A film about the making of the film will be syndicated in mid-May. And, if he isn’t already sounding like he’s working for Stigwood, Bogart is “prereleasing” the soundtrack and spraying.singles into the market in April and May. “Our intention is to have at least five in the Top Ten disco records, by the time the movie opens, and I hope two or three Top Ten singles.”

Along with Donna Summer, TGIF costars the Commodores and a discoful of unknowns. “It is a Grand Hotel in the sense that it takes place in one place in one day. It’s a Chorus Line in the way the characters unfold. It’s American Graffiti in terms of the development of characters.”

Bogart expects a general audience (unlike in Saturday Night Fever, there are no gang bangs or rough stuff), and he has no fears of TGIF drawing only disco freaks.

“The biggest fear I have,” he said, “is will anybody come. I spent two years of my life making this picture and it’s very different from the record business. You put out a record, if it doesn’t happen, you put out another.”

But what happens if you make a movie and the executive producer doesn’t even come? That’s the situation with FM, the Universal film about life and hard times at an FM rock station. Irving Azoff was asked to be executive producer— in this case a fancy title for consultant and connection to his large supply of clients and friends. Azoff arranged for Steely Dan to write and perform the theme song, for Jimmy Buffet, Linda Ronstadt and Tom Petty to make appearances, and helped choose background music. Martin Mull, whom Azoff manages, has a lead role.

After seeing the first rough cut, however, Azoff pulled out and took his name off the credits. It was less than two months before the film’s scheduled release, April 28th.

“It’s an AM movie made about FM radio,” says Azoff. He says he had insisted that the film be authentic. “When shooting started, the very first day, Cleavon Little [who portrays a DJ called the Prince of Darkness] had on a three-piece suit and a tie when it’s supposed to be six in the morning. I knew I had trouble.

“Looking back,” he continues, “I think they wanted me for the soundtrack.” The album, on MCA, includes Boz Spaggs, the Eagles, Dan Fogelberg, Jimmy Buffett and Steely Dan, all Azoff clients. Does he feel used? “Yeah,” he mumbles. Later, he adds: “I feel like the music financed the movie. It was like minimizing our risk. The soundtrack should be a huge success.”

As for the film, numerous scenes were being reshot when Azoff gave his notice. And the character played by Alex Karras—that of a veteran DJ with a serious ratings problem—was in danger of being eliminated, because Karras was unavailable for reshooting.

So with all the money and muscle behind the frantic courtship of music by the movies, there is still no indication that the relationship will do better than most Hollywood affairs. The words far outnumber the songs.

Which takes us back one more time to the Hot Wax party, to the field below the patio, where this lovely hot-air balloon is dancing, just off the ground, all fired up but held stationary by ropes. And on its side, there’s a banner reading.. .all together now, one more time:

THANK YOU, ROCK & ROLL.

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #263 – Cameron Crowe – April 20, 1978