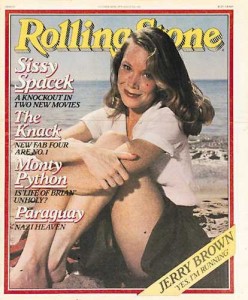

Rolling Stone #302: Sissy Spacek

Sissy Spacek Acts Her Age

From nymphet to telekinetic weirdo to the queen of country and the heartthrob of ‘Heart Beat’

Everyday life for Sissy Spacek began to take on a unique quality three years ago. Passing cars would screech to a halt. Teenagers at the local Jack-in-the-Box would panic. Children clutched their parents and screamed: “It’s Carrie!”

So disturbingly effective was the actress’ portrayal of Carrie White, the high-school outcast with secret telekinetic powers in Brian DePalma’s drive-in epic Carrie, that Sissy won the National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Actress and received an Academy Award nomination for same, followed by a barrage of cover stories trumpeting her incredible promise in two other films released next year – Welcome to L.A. and 3 Women.

Then, with the enigmatic timing of one of her characters, Sissy Spacek disappeared from the screen.

In January, that will change. First arrives Heart Beat, in which Sissy portrays Carolyn Cassady, the wife of Neal Cassady (Nick Nolte) in a love triangle with beat novelist Jack Kerouac (John Heard). Then, in March, she will appear in Coal Miner’s Daughter, based on the life of Loretta Lynn from age thirteen through thirty-five. It is Gary Busey as Buddy Holly on better; Spacek acting and singing in the biography of the queen of country music.

Loretta Lynn and Carolyn Cassady are two roles far removed from the unstable cast of characters she portrayed up through 3 Women. And that is the point. Originally assinged in 1977, this was meant to be a story of Sissy Spacek’s followup to her first wave of success. “I’m holding out for a good part, or else I’ll become a mountain climber,” she vowed then. It seemed a flippant statement from such an insatiable acting talent. But Spacek’s incredibly malleable personality could run, in the course of several minutes, from innocent tomboy to savvy young businesswoman. In the next two and half years, her story would turn into one of Sissy Spacek holding out.

Mary Elizabeth Spacek (The nickname Sissy came from her two older brothers, Robbie and Ed Jr.) is remembered by childhood friends as a born ham. A Christmas Day arrival in 1950, hers was never a cold or neglectful childhood, and she flourished under all the attention. By age nine, she and Robbie had formed a Charleston and banjo duo that was popular around their hometown of Quitman, Texas. By her early teens, Sissy had saved enough baby-sitting money for an expensive twelve-string guitar; for years she carried it around with her like a trophy.

Life in Quitman was dominated by small events like getting caught jumping fences (“Mrs. Spacek, did you know your daughter has been riding our cows again?”), or being called Space-chick in school, or the time her football player boyfriend asked for his ring back but Sissy made him cut it off.

“Things like that,” she told me almost seriously, “made me what I am today. I felt really cradled by Quitman. I felt like my whole life was headed in a single direction. Everything was always going to happen in a certain way. I was going to go the University of Texas at Austin, like my brother Robbie, get involved with music and maybe be a female Buddy Holly. Then I intended to come back to Quitman. Two hundred miles away was worldly enough for me.

“Then something happened to blow the air out of everthing.”

Robbie came down with acute leukemia. Unable to attend classes, he returned home from the university and got steadily sicker.

Right about the same time, Sissy was chosen runner-up in the area’s biggest annual beauty and talent show – the Dogwood Fiesta pageant. Wearing a space dress of her own design and performing two original songs, Sissy so impressed one judge, a newspaperwoman from Longview, that she convinced Sissy the place to start her career was New York City. Seventeen-year-old Sissy asked her parents if she could spend a few days in Manhattan with cousin Rip Torn and his wife, Geraldine Page. They said they’d sleep on it.

“We let her go,” Ed Spacek told me, “because she would be staying with Rip and Geraldine, and because she needed to get out from under the weight of Robbie’s sickness. A lot of parents make the mistake of cutting off their children’s drive. They say don’t a lot. Sissy’s always had that drive. When we slapped Sissy, she’d slap back. Robbie made a point of telling her not to change, and I don’t think she ever did.”

She stayed two months. Young Sissy Spacek in Manhattan for the summer of ’67 must have been a sight to see. Adopting the Twiggy look of the times, Sissy and her guitar were inseparable.

“Geraldine was in a play at the time, and I’d go every day. I was friends with the hairdresser. Later he committed suicide; he was a male prostitute. So pure. I remember just being exposed to all kinds of amazing people. I was never frightened. I didn’t know who anybody was anyway. I could talk to ‘em. I was a blank page.”

There is a story about the time Rip and Geraldine took the blank page to meet Terry Southern, who was working on the screenplay for Candy at the time. “I took my guitar out,” Sissy recalled, “and was singing this song I had written. One of the lines was, ‘I feel his soft touch while I’m sleeping.’ Well, I meant kind of, you know, dreaming or something. It was a nonsexual lyric. To me.

“Terry Southern stopped me right in the middle of the song and asked me if I was a virgin. I was just . . . aghast. You didn’t talk about politics, religion or money where I was brought up. And I was sure you didn’t talk about sex. I was dumbfounded. And I assured him that I was. He asked, ‘How could you have written a song like that?’

“Geraldine appeared to be asleep – she had performed that night – but she rose up from the couch and said, ‘Terry, you don’t have to stomp grapes to know what wine tastes like.’”

Sissy returned to Quitman after school had already started. “Everything had changed,” she said. “I’d missed majorette practice – I didn’t get to be a head majorette. You know, you always build up to your senior year; it’s supposed to be a big deal. Well, it just wasn’t a big deal.”

Her brother died early the next year. “It changed everything. What you were supposed to do was not as important as the things you felt you should do.”

Her room at the University of Texas had already been secured, as was her position with a rush sorority and full schedule of classes. It cost her $200 to forfeit those plans, but Spacek returned to New York the next summer with a new plan.

“I intended to be a rock star,” she recalled. “That was my hanging-around-Greenwich-Village, following-Bob-Dylan period.” An appointment with the William Morris Agency, set up by Rip Torn, resulted in agents politely asking her to come back in a few years. A demo made with Eddie Simon, Paul’s brother, also fizzled. She flunked a Tonight Show audition because of “hoarseness.” Bob LeMond, the manager who later came to represent John Travolta, advised her to “drop the accent and go home.” (Years later, she costarred with Travolta in Carrie. “Now everytime I see LeMond, he says, ‘That’s the little lady I told to go back to Texas.’”) It was not a productive period, but she never failed to leave behind a trail of friends. Though it would have been enough to send Pollyanna packing, Sissy stayed and continued to make friends.

“I remember meeting the Allman Brothers,” she explained. My best girlfriend’s boyfriend was a booking agent. I was at her house, helping her make dinner. Her boyfriend was coming home with some guys. He finally came home with this whole group of guys. There was Duane, who was just about the nicest person I’d met, and his little brother Gregg, who I was kinda sweet on. Gregg had been to the dentist and had his tooth pulled. I didn’t know they were a band or anything. We just hit it off; we were both from the South, and he had this big fat jaw. Then they had to leave. I went home.

“I had a date to go to the Fillmore East, and I was just sitting there, looking at the piano player and the lead guitar player and I said, ‘They look just like the guys I spent the day with.’ Then I went backstage, I couldn’t believe it was them. I always thought rock stars would be crazy, but they were nice little Southern kids. Whenever Duane came to town after that, he’d call up to borrow my twelve-string. He never forgot a name.”

Spacek eventually recorded a single for Roulette Records under the name of Rainbo. It was a folk song she wrote entitled “John, You’ve Gone Too Far This Time,” and in it Sissy scolded John Lennon for posing nude with Yoko on the cover of Two Virgins. Conveniently, she says, she never kept a copy.

Then, finally, came acting. Enrolling in the Lee Strasberg Theatrical Institute, she set about learning the ropes of the Method. Eight months of classes taught her the fundamentals she still uses: “Anything you can use to understand the character and his motivations . . . and to become the character, you should use. I’m not above even poking my eye to help me cry. But the best method for me is to become a blank page. I’ll just wear light-colored clothes, fast, go hiking, do research, and one day I’ll be the character.”

Intuitively curious about most everybody she meets, Spacek claims that her most enriching character study came, not at Lee Strasburg’s studio, but afterward, on the way home. “My girlfriend and I,” she recalled, “would walk to Fourteenth, cut across Seventeenth and Park, then go up to Max’s Kansas City. It was always crowded, always full of the greatest characters I had ever seen. I felt like a beatnik; it was wonderful.”

Spacek moved through the collection of underground media celebrities with ease. “I was anonymous. All my life, you see. I’ve been able to be in all these outrageous situations and I’ve been neutral. It’s probably been my greatest asset.”

She was befriended by Holly Woodlawn, the actress-model, and in 1970 wound up with a role as an extra in Andy Warhol’s Trash. (Years afterward she would thank Warhol for that opportunity when he came to tape her for the cover of Interview after the release of 3 Women. “You were in that movie?” he asked. “Wow.”)

The following year, Spacek got her first real role, as an innocent victim of white slavery in Prime Cut. Filmed in Canada with stars Lee Marvin and Gene Hackman, Spacek remembered: “I was the only one in the cast who believed the script. White slavery? You bet. I believed Lee Marvin would have picked me.”

A crew member recalled that, on the set of Prime Cut, Spacek was “so goddamn sunny she made you want to put on sunglasses.” I asked Spacek how she felt about her cheery image of her work.

“It never bothered me,” she answered. “I am the way I am. I don’t try to exploit my accent or the way I am. I’m just . . . compulsive about making other people feel comfortable. I believe, ultimately, that it’s a better working situation if people are happy.”

New York City began to lose its charm for Spacek just when Prime Cut gave her visibility to continue working. She flew out to Los Angeles to read for Electra Glide in Blue (she did not get the job) and stayed. I knew two people in L.A. and I called them both from my hotel room. One came over and said, ‘Glad to have you here’ and left. The other, a girlfriend from Prime Cut, came and got me and we moved in together. She’d found a great house in Beechwood Canyon and we pooled our money – we were living in the lap of luxury.”

Another turning point came when Sissy was sent out to a job interview with writer-director Terrence Malick. In describing the meeting, she recalled the most minute details about Malick’s rented Spanish house, even the kefir drinks that Malick’s wife served. “From the moment we met, it was . . . neat. We talked about Terry’s script and I was just fascinated. For hours, I forgot my girlfriend was waiting for me out in the car.”

It was the beginning of Badlands and the role that many, including Sissy, still believe was her finest. An exacting writer who had worked years honing the script, Malick drew the story from the Charles Starkweather killing spree of the late Fifties. Starkweather executed his small-town girlfriend’s father so the two could take off on what became an interstate crime spree. The girlfriend was jailed, while Starkweather was executed. Badlands is the story of Kit (Martin Sheen), an excitable boy who collects garbage (“It’s just a job, I’m not in love with the stuff,” he tells Sissy in one of the first scenes), falls for the baton-twirling neighborhood girl Holly (Spacek), kills her father (Warren Oates), and as fugitives, they achieve their dream to be together out of town. Only they find there isn’t much to talk about. In the film’s best scene, Sheen, about to be captured, tells the authorities that his girlfriend is blameless and shouts to her as he runs away: “Grand Coulee Dam, New Year’s Day, 1963. Meet me there.”

There were no major stars, but few who saw Badlands could dispute that it was among the finest films in an otherwise bleak 1973. Unfortunately, because of distributing problems, mostly only critics had the opportunity to see the film. But those critics were very vocal about the luminous performance of Badlands’ star – twenty-two-year-old Sissy Spacek.

“Terry Malick gave me respect,” she said, “and that reinforced everything for me. He allowed me to grow an enormous amount. His words . . . they feel so good to say.” She runs her tongue over her teeth, like in a toothpaste ad. “Every frame is a painting with Terry. We all worked so long on the characters that when we finally saw the film it was like, ‘Oh gosh, Kit and Holly will never exist again.’ Now, whenever any of us get together, we go right into Badlands dialogue. It can be totally bewildering to outsiders.”

It was on the set of Badlands that Sissy and set designer Jack Fisk first met. They were drawn to each other, according to Fisk, “because we had the same kind of conviction to work.” Fisk had heard about Malick’s project through a friend who was the production manager, and he became so enthralled that he proceeded to research the period before he had even met Malick. When the two finally did get together, they hit it off and Fisk was hired.

Two years later, Fisk and Spacek were married. Fisk is a highly respected and well-paid artist in his own right and they can afford each other’s selectivity. Ever since Badlands, they have often worked together on projects to form a kind of flying wedge. In a business where many failures are blamed on the speculative nature of collaborative art, Spacek and Fisk work with a tightknit set of cameramen and crew friends.

“You could wait another lifetime for a role as good as yours in Badlands,” Shirley Jones once told Spacek. And for several years, it looked like it might be the case. After 1973, Sissy took few of the less-than-abundant roles offered her. Most notable was the TV movie Katherine, writer-director Jeremy Paul Kagan’s story of a blue-blooded college girl turned radical. Filmed in eighteen days, it matched her with then-obscure Henry Winkler, who played a Weatherman. “I took a few jobs in television,” said Spacek. “Stuff that you forget until someone calls up and says, ‘Hi, I’m watching you on The Rookies and I don’t believe what you just did.’”

Finally, in 1976 came the part of Linda Murray, the maid in Alan Rudolph’s Welcome to L.A. To prepare for the role of a rock star’s housecleaner, Spacek donned her blank-page look and spent time seeking out maids around town. Her part was modeled mostly after two women she met who cleaned houses in their bikinis, and with them in mind she turned in a characterization that entranced Rudolph’s mentor, Robert Altman. The film, however, sat on the shelf for more than a year while its finances were sorted out.

In the meantime, Fisk took a job as art director of Brian De Palma’s next film, Carrie. “Brian called one day and told me to get the book and read it,” recalled Sissy. “So I went out and got it and I was just horrified. But I knew what kind of sense of humor he had and I was anxious to do it.”

Spacek read for several of the parts, but De Palma had her in mind to play Chris, the bad girl (played by Nancy Allen, De Palma’s wife). She had made plans to return to New York for a Vanquish commercial when De Palma called again, mostly out of courtesy.

“He told me that if I wanted to, I could try out for the part of Carrie White, but that I shouldn’t miss my commercial. There was another girl that he was set on and unless he was really surprised, she was the one.” In recounting this tale, Spacek assumed a look of gritty determination. “I hung up and decided to go for it.”

For her screen test a couple of days later, Spacek dug out a navy blue sailor’s dress she hadn’t worn since grade school. She slicked her hair with Vaseline. She filled her head with thoughts of the girl who had been ridiculed at her high school. (She was beautiful,” Sissy explained, ‘but she was poor and didn’t have money for clothes. So she wore antiques, and the kids were really brutal with her. I remember always loving her clothes, baggy and old-fashioned like they were. She was barefoot most of the time, but there was no hip, groovy scene then.” Spacek looked down at her own bare feet. “And in the end, it’s the outsiders who become the ones you emulate.”)

Sissy sat in the studio parking lot after her screen test while Jack looked at the film with the company brass. Fisk then came running out and jumped in the car, shouting, “You got it!” “We sped off,” recounted Sissy, “before anybody could change his mind.”

(“The other girl played Carrie as someone you could hate,” Fisk said. “You could understand why everyone made fun of her. You didn’t really care about her much yourself. Sissy, you felt hope for. You could almost fall in love with Carrie White when she played her, and it made the film twice as effective. De Palma said there was no contest.” Fisk added, “She’s so strong when she’s getting into a role.”)

“I have always tried to present characters who are human and vulnerable; somehow they’ve all turned out macabre and vulnerable,” said Sissy Spacek, settling herself on the porch table of her immaculate Topanga Canyon home. It was our first conversation, back in 1977, and more than a year since she’d made Carrie. She shrugged, choosing her Polyanna outlook. “I’m at a really neat stage now, though. I can choose. If I’m careful about not losing momentum, I can be selective. Most actors have a very passive role in things. I intend now to just wait for the right part.”

Throughout our interview Spacek had been warm and hospitable to the point of near suspicion. But after a while she confided:

“You know, I’ve really been doing a lot of talking about myself. I went out on this tour for 3 Women and, you know, you can’t help but see things that you really believe in turn into . . . interview fodder. Then these stories come out, and they’re all kind of the same.”

Seeing as how I was there for a quick interview with which to jump shameless on the bandwagon, I suggested an alternative: an interview centered on her next character. The one, she’d said, that would be a true departure.

“Neat,” she responded conspiratorially. “Instead of doin’ a regular interview, we’ll just go horseback riding and talk. In another week I’ll be able to talk all about the next movie. I play a wonderful woman named Melaina, who meets her lover in Vienna. It’s the best role I’ve had since Holly in Badlands.”

On the way home from a charming but interviewless afternoon, I began to wonder just how sincere it all really had been.

The phone rings. “Hi,” says an unmistakable accent. “Let’s go horseback riding.”

In an afternoon of scaling the hills around Topanga with Spacek and Fisk, discussing mostly Sissy’s childhood and family in Quitman, the subject of her next role did not come up.

Upon returning home, Fisk immediately collapsed on the sofa. Leaving her immaculate house lit only by the hazy shadows of a skylight, Sissy sat cross-legged in front of the fireplace.

“What happened to Melaina?”

She seemed crushed. “It fell through. The financing fell through. It’s difficult to just let go of a character. Especially after you’ve been preparing and researching for weeks . . . “

She sighed heavily. “I feel like, why should I just go out and find another movie. That’s the question, isn’t it?”

Or perhaps more accurately, just what did Hollywood have to offer one of its most valuable actresses as a followup to Carrie?

“Well,” said Sissy, “the answer is – a lot of sequels to Carrie!” She laughs. “Sometimes the ego is bigger than greed.”

“See those?” she asked. “See that stack of scripts? Those are all parts for weird teenage girls. Murderous teenage girls. Nymphet, telekinetic girls. All the parts that Jody Foster turned down. I seem to get them all. They don’t realize I’m not a teenager. I’m twenty-six and it’s getting harder to feel like a teenager.”

She pounded a small fist into the wooden floor. “I feel like maybe it’s time to play a woman. You know? A normal, attractive, even sexy woman.”

In the next year of watching Sissy cultivate, then never play, three other roles, for one detail or another, I would come to appreciate that moment more than any other. Words sometimes seem a commitment she’s reluctant to make. A somber moment of self-reflection often got interrupted by something more visually exciting: “Did you see those ducks coming across the lake? There was a mama . . . and four little babies . . . it was . . . .” She would try to pluck another word out of the air, but invariably settled for her favorite adjective – neat. It sometimes seemed that one could best gauge her moods by the verve with which Sissy Spacek said “neat.”

Several weeks later, another interview attempt:

“What was it like working with Robert Altman on 3 Women?”

“It was neat,” said Spacek. “We all stayed in this motel in Palm Springs. I took a lot of pictures.’ She runs into a back room to get the stack of photos.

“Now these,” she said, “are the real ‘three women.’” She produced a grainy photo, taken off a television set, of three matronly gospel singers in full throes of song. “I took this one Sunday morning.”

She set the shot against an ashtray.

“Here’s Bob.” A shot of the imperial presence himself, Altman, seated in his hotel room. “His room was down the hall.” She placed the photo about a foot away, against a bowl.

“Here I am.” Sissy, sitting on her bed, captured in the mirror above the television set. She places it in front of the three women.

“Here’s Shelly.”

Sissy made only a few appearances after 3 Women, all on television. Sissy had casually dropped a baited line in a People magazine profile that she had been taking tap-dancing lessons in anticipation of doing a Forties musical. Sure enough, an offer came for exactly that: a project for public television called Verna: USO Girl. The story was about a spirited but acutely untalented dancer-singer sent to wartime Germany; she dies in the final scene. It was a meaty part by TV standards, but frustrating, too.

“Everything I did,” Spacek explained, “the director would say ‘Great.’ I was not used to working that way. I only learn from people I work with. Ultimately, you have to work for your own enlightenment – for smarts – or it gets boring. I don’t like to do something just to prove I can do it.”

There were elaborate kudos for her performance inVerna; they fell on polite but deaf ears. In the words of Jack Fisk: “She thought her career was over when she saw it.”

Spacek did not win the Academy Award for Carrie in 1977 (Faye Dunaway won, for Network). On the phone the day after, though, she was full of enthusiasm. “One the one band, it’s a big deal. You see it every year on television. Suddenly you’re there. You just have to remember what it is. It isn’t a communist plot. It’s an honor. People know that it’s not the last word.”

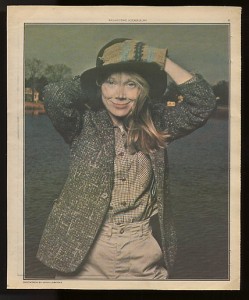

In the Spring of 1978, Sissy invited Anne Leibovitz and me to meet her in Quitman, where she was taking a short vacation.

We arrived in the pleasant town of Quitman in time for a spectacular sunset, the kind that locals watch like others would television. (Life in East Texas, it seems, is four-fifths sky.) Five miles out of town, we joined Sissy at her cabin on the edge of Lake Quitman. Her father, a retired county agricultural agent, was doing odd jobs around the yard.

“We went to Mineola to see Carrie,” Ed Spacek told me later. “She was excellent in the film, and we thought De Palma used some good gimmicks. The hand scene was excellent.”

A rugged man in his sixties, with the incongruously gentle face of Gene Kelley, Ed Spacek and I were out in the middle of Lake Quitman on a fishing boat. No bites.

“We’ve been worrying a bit about Sissy lately,” he offered. “She’s passed on so many projects, you know, Rip is an actor who has mouths to feed, like many of them. He admires Sissy for being able to hold out. But he worries for her, too. We don’t want to see her lose what she’s built up to.”

Over dinner that night at a local catfish house, the Spaceks proved an extraordinarily close family. The conversation ranged from the neighbors who served dinner in a Colonel Sanders box to which studio would be a good place for Sissy to work again. When she left the table, I casually asked if her parents might set aside a few hours to talk about their daughter. Ed Spacek instantly turned solemn.

“We’re not new to show business,” he said. “Rip is a relative; we know some of the traps you can fall into. And we just don’t want to get in Sissy’s spotlight. It’s a decision we made long ago.”

After dinner, when her parents had returned to their home in central Quitman, I took a walk out to the pier with Sissy.

“You have the best relationship with your parents that I’ve ever seen.”

“It certainly has changed over the years,” Sissy remarked, pulling a huge red and black Pendleton jacket around herself. “They’ve been real champs. When I first left Quitman they were unsure. But I always come back to visit. Everytime I’d come back I would be something different. Black eyes. Short, short skirts. They’d always say, ‘Welcome home, Sissy honey, you sure you aren’t a little cold in that?’”

At a small artist’s opening in Santa Monica in 1978, a man with a deep tan approached Sissy: “I remember you,” he said. “You brought cookies – and good vibes. My lady just said to me the other day, ‘Remember that party we had out at the house in Zuma Beach in ’71? That was Carrie who brought the cookies.’” He opened his mouth to laugh, but no sound came out. “Vin Parker.”

Sissy Spacek smiled cheerfully. “Nice to see you again.”

“Now who’s that actor you’re living with?”

“Well,” said the actress in her East Texas twang, “you’re probably thinking of my husband, Jack Fisk. The set designer. He’s right over there.”

“No, no,” said Vin Parker (not his real name). “Didn’t you live with Paul Simon?”

“No,” said Spacek. “You’re thinking of Shelly Duvall.”

Vin Parker nodded thoughtfully. “Talented little guy, Paul Simon. We’re doing a film with him.” He finally let go of her hand. “So what’s your next picture?”

“It’s still up in the air,” Spacek responded. It was a question with which she was more than familiar.

“Well,” Vin saluted before moving on, “hope you find some work. You’re a real talent.”

In 1976 Doubleday issued Loretta Lynn: Coal Miner’s Daughter. It was an excellent, offbeat biography (cowritten with George Vecsey) of a genuine American folk hero. The queen of country music is still the wife of the farm worker she married when she was thirteen. The book’s success surprised even the publishers. To date it had sold over 1.5 million copies. The film rights were purchased by Universal.

Some time after that, an agent showed Loretta Lynn a book of photos and asked her who she thought could play her in her life story. Lynn flicked through the photos and came upon a picture that struck her as perfect.

“Sissy Spacek,” said Loretta Lynn.

And from that moment onward, the issue was as good as settled. Lynn began nightly announcements from her concert stage that Sissy Spacek would be starring in the movie of Coal Miner’s Daughter.

Spacek herself first heard of the casting when relatives read it in a gossip column. “I always thought country music was corny,” said Spacek. “All those things you think, I thought. I went out and got the book and found that I really admired her as a women. But I still wasn’t sure there was a movie there.” And yet there was Loretta, crisscrossing the country with plans to the contrary. Sissy Spacek was sure of one thing – it was time to meet the queen of country music.

The day before Annie Leibovitz and I were to leave Quitman, we piled in a car with Sissy’s mother and took off on a two-hour drive to Shreveport, Louisiana, where Loretta Lynn was performing with Conway Twitty.

Lynn’s bus sat outside the backstage door, a proud monument to her nearly constant road schedule. Forget about the albums that still seem to come out every few months. Forget about Lynn’s much-publicized nervous exhaustion breakdowns. Forget that she still writes many of her own songs. Loretta works every market, even signing several hours’ worth of autographs for those who wait in line after a show. She does this because the most important thing in her life is “a-singin’ for y’all.”

Loretta’s surprise visitor was ushered into the bus. Lynn emerged from the back bedroom wearing a brilliant red dress, saying, “Bam. Bam. Bam. All I hear are them dad-gum drums a-beatin’ in my ear.”

Then she saw Sissy, diminutive and wearing wire-rimmed glasses that allow her to look her age. Loretta gave Sissy a warm hug.

“We’re exactly the same height,” Sissy laughed. “Five feet two and a half.” They promptly began chatting like old bridge partners, about the drive, Loretta’s twenty-seven goats, and about the movie. “You’re pretty,” Loretta said.

Lynn’s son and occasional backup singer, Ernest Ray, came bounding onto the bus. “Hey Mom.”

He stopped and looked at Sissy, who had just taken off her glasses. “Sissy?” he said rapturously.

She nodded, wide-eyed.

“Well you just stop gumming her,” Loretta shoosed. “He thinks he’s Jesus. You get out of here, Ernest Ray.” She playfully chased him out of the bus before she retired for a few minutes into her back room for makeup.

By the end of the evening’s concert, it was not hard to see that what began as pure curiosity had grown to near obsession. Sissy was chatting with all of Lynn’s entourage, promising to see them again soon. Sissy turned to me, transported. “There is an incredible story to be told here.”

All the way home to Quitman, Sissy practiced the inflections until they were flawless. “Bam. Bam. Bam,” she said. “All I hear are them dad-gum drums a-beatin’ in my ear.”

During a breakdown in negotiations over Coal Miner’s Daughter, Spacek had met with writer-director John Byrum (Inserts). Byrum had told her over dinner about his newest script, a film about the relationships between Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady and Carolyn Cassady, the square Bennington student who married Neal and became companion to both (“We didn’t do anything wrong; we just did it first”). For Spacek, it sounded instantly like the stretch she had been waiting for – an elegant woman who ages from twenty-two to forty-three, and in her words, “I get to play a woman and they play children.

“I fought tooth and nail to get that part,” she said in our last conversation, over lunch in an L.A. restaurant. She had decided she was going to do Heart Beat, and, in the way that had become second nature to her when she made such decisions, Spacek had stormed ahead with hundreds of hours of research.

But her hold on the role had slipped several times. “Orion Pictures felt she wasn’t enough to make the picture lucrative,” explained John Byrum. “Diane Keaton had expressed strong interest in doing the part, and they said, ‘If you get Keaton, we’ll give you all the financing you need.’ You have to remember, this happened the week she won the fuckin’ Oscar. She was the hottest actress in the business. It looked pretty bleak for Sissy.”

Byrum himself had become convinced that Sissy was right for the part only after prodding the film’s producer, Ed Pressman. “The thing that really did it was that she was talking like a shitkicker, just being that kind of Texas bizarro. And all of a sudden, she asked, ‘Do you think I can play this part?’ She said it so vulnerably. I was thinking to myself, ‘No way.’ But I said, ‘I don’t know, I kind of see it like Grace Kelly. Can you act like Grace Kelly?’

“She said, ‘Just a second,’ and when she turned around, she looked totally different. She did this Grace Kelly impersonation, this velvety Philadelphia debutante: she was just a different fucking person. I couldn’t believe it. That’s when I knew I had to have her. And when she was through, she just turned into Sissy again.” Byrum shook his head and laughed. “Then I realized, man, there ain’t no Sissy. She’s just a great movie actress.”

But with Keaton’s interest in the part still weighing heavily with the studio, the time came to inform Sissy. Pressman and Byrum met Fisk and Spacek for dinner. “We had to kind of let her down easy,” said Byrum. “I knew she was already into the part, but the decision hadn’t been made about Diane Keaton yet.”

“I just freaked out,” Spacek told me. “Because at that point I’d done about 4000 pages of research. Then it turned out that maybe I wasn’t going to do the film. I was drinking this glass of wine and . . . I couldn’t control myself. Outwardly everything seemed fine. But I broke this wine glass in my hand. Broke it.”

Several weeks later, she won the role over Keaton and was beginning filming in San Francisco. Pressman walked up and presented her with a piece of the shattered glass: “That is when you cinched it.”

“In the end,” Byrum explained, “she’s just so amazing that I stuck by her. I refused to give Diane Keaton acting approval . . . we just wouldn’t meet her terms. Sissy had a lot to overcome with this role. One, she hadn’t done a movie in two years. Two, being jerked around for weeks on this Diane Keaton thing certainly couldn’t have helped her self-confidence. Third, it was the first time she was playing an adult. The fact that she overcame all these and did a remarkable job proves that we made the right decision.”

Much will be written about the rather cavalier relationship between some scenes and the real facts of Kerouac’s life. “I did the research and it’s all true,” Byrum told me last month. “I’d like to think that it’s possible to go beyond the usual film biography. It’s literature. Maybe it is an inaccurate representation, but it should be judged totally. It’s mythology with recent characters. I really wish I’d changed their names because of this backlash. Nobody judges Citizen Kane because Marion Davies wasn’t a singer, she was an actress.”

For me, Heart Beat is an ensemble presentation and one in which Spacek is as powerful for the room she leaves her costars as for what she herself says.

“I don’t look at myself as a professional,” she told me that last time we talked. “I learned from each new set of people I worked with. It was a trying experience, keeping the balance from slipping when the characters are that close. But then, I was also working with a bunch of animals: Nolte, Heard, Byrum. I really love them, but they drove me to drink.” (“Part of the reason we were all needling her was because that’s what Jack and Neal did,” Byrum said.)

As she laughed, I realized that her accent and attitude – even the way she walked in – had changed subtly. The lingering effect, I guessed, of Carolyn Cassady. I remembered something her brother Ed once said:

“Sissy has always been the same determined person, but she’s always searching for interesting variations. She was in New York once and it started raining, so she went under this awning to get out of the rain and I looked next to her. There was another girl standing there with a short skirt and big Twiggy eyes. The next day Sissy had become that girl.

“You know, we all used to sit around in Quitman waiting for her to come home. Wondering who would be standing there when we opened the door.”

“I have learned a lesson,” Sissy said. “At that point in my career, I had to wait for the right part. And when you spend two years not working, you forget what it’s all about. Or if you don’t, you think you do. And it’s such a frightening thing, because so much is riding on one performance. But overall, the hardest part isn’t the acting. It’s telling people ‘nothing’ when they ask you what you’re doing.”

“Doesn’t all the doubt seem silly to you know?”

“There was never any real doubt,” responded Sissy. She thought for a moment, then leaned over. “You aren’t going to have me saying ‘neat’ all through the article, are you?”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #302 – Cameron Crowe – October 18, 1979