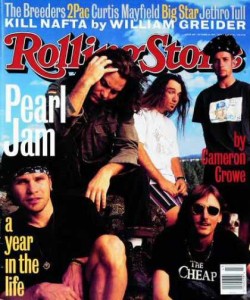

Rolling Stone #668: Pearl Jam

Five Against the World

Pearl Jam emerge from the strange daze of superstardom with a new album full of rage and warrior soul.

There are two Eddie Vedders. One is quiet, shy, barely audible when he speaks. Loving and loved in return. The other is tortured, a bitter realist, a man capable of pointing out injustice and waging that war on the home front, inside himself. On a warm and windy late-spring day in San Rafael, California, it’s easy to see which Eddie Vedder is shooting baskets outside the Site, the recording studio where Pearl Jam are finishing their second album. It is tortured Eddie, the one with the deep crease between his eyebrows.

“Your shot,” calls Jeff Ament, the group’s bassist. He bounces the ball to Vedder, who takes a long outside jumper. It rattles into the basket and rolls away. By the time Ament retrieves the ball, Vedder has already disappeared into the studio. His mind is on a new song, “Rearviewmirror.” This is the last day of recording at the Site, and the track’s fate hangs in the balance. It’s a song about suicide… but it’s too “catchy.”

The choice of studio seemed perfect back in February, when the band decided to record the new album here. This idyllic studio compound in the hills outside the San Francisco offered privacy and focus. Keith Richards had recorded here; his thank-you note to the studio is framed on the living-room wall. This is gorgeous country, where locals look out at the expansive green horizon and say things like “George Lucas owns everything to the left.” This is where Pearl Jam would face the challenge of following up Ten, one of the most successful debut albums in rock. There was only one problem.

“I fucking hate it here,” says Vedder, standing in the cool blue room where he is about to sing. “I’ve had a hard time.” He places the lyric sheet on a stand between two turquoise-green guitars. “How do you make a rock record here? Maybe the old rockers, maybe they love this. Maybe they need the comfort and the relaxation. Maybe they need it to make dinner music.”

Frustrated, Vedder shakes his head. He pulls at his black T-shirt, uncomfortable in his own skin. A long moment passes. Finally, producer Brendan O’Brien speaks over the intercom. “Ready to give it a shot?”

“Sure,” Vedder says quietly, turning his back for the vocal. He slips on headphones, and for a long time the only sound in the room is his tapping foot.

“Took a drive today,” he sings. “Time to emancipate/I guess it was the beatings/Made me wise…” He holds a shaking hand to his head. “But I’m not about to give thanks… or apologize.” Now listening carefully, his weight shifts from foot to foot. He growls and begins spitting on the floor. “Divided by fear…” Louder now. “Forced to endure/What I could not forgive…” He’s bellowing now, eyes shut. “Saw things…” The room is filled with his anger. “Clearer… once you were in my…” Eight feet away, a snare drum leaning against the wall starts to shake. “Rearview… mirrorrr!”

In another part of the building, Ament, the band’s resident artist, prepares for a group meeting about the new album cover. For months, the unwritten rule had been don’t talk about it. Just make the record. Forget about the pressures on the other side of that hill. But now decisions must be made, and the band slowly gathers in the kitchen to look at Ament’s ideas.

“I’ve been thinking about windows,” Ament says, fighting nerves, passing his artwork ideas to the other members. Ament’s distinctive hand-scripted style adorns all the group’s T-shirts and record releases. On the table before them is a complex collection of his photos and sketches.

“Cool,” says Vedder softly, just returned from the studio and still hunched from the emotional vocal. Stone Gossard and Mike McCready, the band’s guitarists, study the ideas with growing enthusiasm. Buoyed, Ament continues. He likes the idea of contradiction. Conflicting images. The five members kick the concept around until it sticks. Contradiction. There is the lull that follows a winning idea.

“So are we talking about ‘Daughter’ as the first single?” drummer Dave Abbruzzese asks casually.

Suddenly, all air leaves the room. The other four members dog pile on Abbruzzese. What single? One meeting at a time! What do you mean, single? Abbruzzese shrugs. Perhaps it’s still a little too soon to mention the unmentionable. Soon, the subject returns to the album-cover art. Abbruzzese suggests adding a battered and bolted New York City apartment window to the artwork. The idea is instantly accepted and the meeting ends on an exuberant note. The band disappears to play softball while Brendan O’Brien finishes the mix of “Rearviewmirror.”

Abbruzzese stays behind, nursing a sore wrist. (He occasionally suffers from carpal-tunnel syndrome, which causes numbness in three of his fingers.) “To me, when I was younger and I heard about a band selling a million records, I thought the band would get together and jump up and down for at least a minute,” he says with a wide-open East Texas laugh, “and just go, ‘Wow, I can’t believe it.’ But it doesn’t happen that way [in this band]. Me, I flip out. I jump up and down by myself.” For Abbruzzese, who co-wrote the album’s opening track, “Go,” it’s sometimes hard to watch his band mates deal with success. “There’s a lot of intensity over decisions,” he says cheerfully. “And I think it’s great. But every once in a while, I wish everyone would just let it go. Make a bad decision!” He looks out at the same green forest Vedder had raged at earlier. “Look at this place! It’s paradise.”

Sitting in a downtown-Seattle coffee shop a few weeks later, Stone Gossard analyzes the combustible nature of his band. “I think we’re doing fine,” he says in the clipped rhythm of an athlete. “I think we made a great record. Nobody’s out buying limos and thinking they’re the most amazing thing on earth. There’s a natural balance in the band where we need each other. Everybody sees things from their own angle, and all those angles are the archetypes of the things you need to really cover your ass. It’s what makes a band to me.”

And he has heard the criticism of Pearl Jam’s success. “If somebody wants to say, ‘You guys used to be my favorite band, but you got too big’ — to me, the problem with getting too big is not, innately, you get too big and all of a sudden you stop playing good music,” Gossard says. “The problem is, when you get too big, you stop doing the things you used to do. Just being big doesn’t mean you can’t go in your basement and write a good song. I think people are capable of being a lot bigger on that rad big scale.” He laughs. “A lot more people are capable of being big out there that just don’t give themselves a chance.”

At first, the songs on the new album, Pearl Jam, came in a burst. The initial week of recording at the Site had produced “Rats,” “Blood,” “Go,” and a slow, potent version of their previously unrecorded stage favorite, “Leash.” Then the band hit a wall. Vedder disappeared into San Francisco, often sleeping in his truck to preserve his fighting spirit. Hiking, he’d even picked up poison ivy. “He needed to get in the space of his songs,” says Ament. “Soon we were back on track.”

Pearl Jam is the band’s turf statement, a personal declaration of the importance of music over idolatry. But the burden of Pearl Jam’s popularity has fallen most solidly on Vedder, who spent much of his off-season wondering about the effects of being in such a high-profile band. Vedder had — uncharacteristically — even gotten into a barroom fight defending the band. (In a Waits-like voice, he offers a snippet of an unrecorded song that he has written about it: “Gave myself a black eye/To show off just how I was feeling.”) And one night, while sitting out on a deserted coastal sand bluff, contemplating life after the death of a friend, guitarist Stefanie Sargent of 7 Year Bitch, he heard strange voices coming from the hill behind him. They were singing “Black,” the fragile song that to Vedder had come to symbolize the overcommercialization of the band. He’d fought to keep it from getting overplayed, didn’t want a video made of the song. Vedder hiked out of the bushes to ask the surprised hikers not to sing the song. Months later, he still remembers their odd and concerned looks as they faced the angst-filled author of the song.

“I had a hard time getting away,” Vedder says now with a laugh. But as Ament says, the struggle is everything. “The push and pull,” he says, “is what makes our band.”

* * * *

“Let’s do ‘Black,'” says Gossard.

It’s rehearsal time back in Seattle, June 1993. Later in the summer, Pearl Jam will do a brief “fun” tour of Europe, opening shows for Neil Young and U2, and the band has rented out the downtown Moore Theater for practice. Half-seriously, Gossard asks that the stage lights of the empty theater be darkened. (They are.) He begins strumming the simple chords that open this anguished song to a former lover. Then, hands in pockets, Vedder eases into the words. He gives himself, wrenchingly, to a thousand empty seats. When it’s over, there is a buzz in the air. The band is clearly energized.

Soon Pearl Jam are racing with a new riff by Gossard. Abbruzzese tries a few different feels, locks in on one with Ament. Then McCready adds a spitfire lead. Like McCready himself, his playing is quietly expressive marked by sudden explosions. Now Vedder joins in, trying random lyrics (“When it comes to modern times/You’re standing in line”). His omnipresent yellow-tweed suitcase, the one filled with journals and lyrics and masks and tapes, is open and spread out onstage. He selects phrases and thoughts as the band blazes behind him. Before long, they’ve honed loose versions of two new songs. At the heart of Pearl Jam is the relationship between Gossard and Vedder. “I consider us to be very different people,” says Gossard, whose razor-edged wit is far different from Vedder’s deadpan irony. “Almost polarized in a lot of ways. I mean, name any given issue, and we’ll take opposite sides of it. We give each other the total different end of the spectrum so we can always somehow find the middle. My goal, what I really want to achieve, is not to need him. Because he is needed by so many people who don’t really understand him.”

Later, Vedder grabs a pitcher of beer at a bar next door, the Nightlite, and unwinds from the rehearsal. He reflects on singing “Black” for the first time in months. “There are certain songs that come from emotion,” he says. “It’s got nothing to do with melody or timing or even words; it has to do with the emotion behind the song. You can’t put out 50 percent. You have to sing them from a feeling. Like ‘Alive’ and ‘Jeremy’ to this day – and ‘Black.’ Those songs, they tear me up.”

Ament is sitting next to him. The two have not been out together socially since the 1992 Lollapalooza tour. They share the easy camaraderie of music lovers. “My relationship with the band,” Vedder says, “began as a love affair on the phone with Jeff.” Soon the two musicians are recalling the early history of Pearl Jam, the scuffling days of only two and a half years ago.

It had all begun with an unassuming tape marked “Stone Gossard Demos 91.” The guitar-god magazines have only recently discovered it, but most Pearl Jam songs began life as a Gossard riff. One of his early favorites was a song called “Dollar Short,” an unfinished track that he’d started working on back when he and bassist Ament were in Mother Love Bone. Love Bone was the promising Seattle hard-rock band they’d formed after the breakup of their previous group, grunge pioneers Green River. When Love Bone singer/songwriter Andrew Wood died in 1990 of a tragic heroin overdose, Ament — the Montana-born son of a barber — downshifted, playing around town with a group called the War Babies and returning to his other love, graphic arts. Gossard — a Seattle native whose father is a lawyer — barely put down his guitar, playing constantly, moving away from the trippy atmospherics of Love Bone and toward a hard-edged groove. Part of the new blueprint was “Dollar Short.” Eventually Gossard called in McCready, an explosive lead guitarist who had been so bummed out by the breakup of his own Seattle band, Shadow, that he’d started turning into a Republican — literally. He’d cut his hair, was working in a video store and was reading a book by archconservative Barry Goldwater. “I was becoming a staunch conservative,” McCready says, “because I was so depressed.” Gossard saw him more as his new secret weapon for the band he wanted to form.

“Whatever you’re playing,” says Gossard, ” ‘Cready comes in and lights the fuse.”

As the Seattle sound started to gather momentum around them — Nirvana were about to enter the major-label arena, Sub Pop Records was flourishing — Gossard and McCready jammed in the attic room of Gossard’s parents’ house. That room had already been the musical hothouse for Green River and Mother Love Bone. When Ament joined the Gossard-McCready jams, inspiration struck again. “I knew we had a band,” McCready says, “when we started playing that song ‘Dollar Short.'”

Dave Krusen joined the band later, playing on Ten, but soon left to deal with some domestic problems. He was replaced by Abbruzzese, who had been playing in a funk band and co-hosting a radio show, “Music We Like,” in Houston. At first, Abbruzzese was tentative about playing rock full time; after two shows, he’d tattooed Ament’s stick-figure Pearl Jam logo on his shoulder.

Today, listening to Gossard’s original ’91 demos is not unlike hearing Ten without the vocals — powerful but incomplete. The missing piece, it turned out, was in San Diego. Originally from Evanston, Illinois, Vedder — better known on the San Diego music scene as “the guy who never slept” — had brought a Midwestern work ethic to the sunny beach community. Working at hyperspeed, laboring days at a petroleum company to finance his budding career as a singer and song-writer, Vedder had befriended Jack Irons, formerly of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Irons passed along Gossard’s tape.

The demo tape from Seattle contained five instrumentals, Vedder remembers, but there was something about that one song, the one with that great bridge, that was triggering things that Vedder had kept long contained. It all came to a head one morning in the fog as he was surfing, the morning “Dollar Short” became a song called “Alive.”

Vedder raced back to the Mission Beach apartment of his longtime girlfriend, Beth Liebling. Working from yellow Post-it pads lifted from his job, Vedder taped himself singing over three of the instrumentals. Together the three songs told a story, as Vedder recalls today, “based on things that had happened, and some I imagined.” The “mini opera” tape was carefully designed by Vedder, the graphics Xeroxed at work and the package entitled “Mamasan.”

Sitting in his apartment in Seattle, Ament listened to the tape three times and picked up a phone. “Stone,” he said, “you better get over here.”

By the time Vedder arrived in Seattle, he’d already written “Black.” All he’d requested in his earlier, lengthy phone conversations with Ament was not to waste time. He wanted to come straight from the airport — right to their rehearsal room — and make music. And that is what happened. The first song they played together was “Alive.” Within a week, they were a fully functioning band. And Vedder’s creative floodgates were wide open. Most of his songs, from “Why Go” to “Oceans,” were real stories about people he knew. Some of them contained riddles, private messages to himself or friends. Even the lyrics printed on Ten are only partial, but it’s hard to dispute the pain in his delivery of such aching lines as “Daddy didn’t give attention/To the fact that Mommy didn’t care.”

“I don’t know where all those songs came from,” says Ament. “I know a little about his childhood. I know he loved [The Who’s] Quadrophenia… I guess I don’t know many details.”

“Alive” set the tone for everything that would follow. The first song on Ten was also the first song to bring attention to the band. It was clearly Vedder’s creative breakthrough, and the band’s initial video celebrated a cathartic live performance of the song. In an early Los Angeles Times review, writer Chris William had even compared the song to The Who’s “My Generation.” Today, “Alive” is a Gen X rallying cry, but tonight, sitting in the Nightlite, Vedder reveals the true meaning of the song.

“Everybody writes about it like it’s a life-affirmation, thing — I’m really glad about that,” he says with a rueful laugh. “It’s a great interpretation. But ‘Alive’ is… it’s torture. Which is why it’s fucked up for me. Why I should probably learn how to sing another way. It would be easier. It’s… it’s too much.”

Vedder continues: “The story of the song is that a mother is with a father and the father dies. It’s an intense thing because the son looks just like the father. The son grows up to be the father, the person that she lost. His father’s dead, and now this confusion, his mother, his love, how does he love her, how does she love him? In fact, the mother, even though she marries somebody else, there’s no one she’s ever loved more than the father. You know how it is, first loves and stuff. And the guy dies. How could you ever get him back? But the son. He looks exactly like him. It’s uncanny. So she wants him. The son is oblivious to it all. He doesn’t know what the fuck is going on. He’s still dealing, he’s still growing up. He’s still dealing with love, he’s still dealing with the death of his father. All he knows is ‘I’m still alive’ — those three words, that’s totally out of burden.”

Elvis’ “Suspicious Minds” blasts on the jukebox as Vedder continues. “Now the second verse is ‘Oh she walks slowly into a young man’s room… I can remember to this very day… the look… the look.’ And I don’t say anything else. And because I’m saying, ‘The look, the look’ everyone thinks it goes with ‘on her face.’ It’s not on her face. The look is between her legs. Where do you go with that? That’s where you came from.”

“But I’m still alive. I’m the lover that’s still alive. And the whole conversation about ‘You’re still alive, she said’ And his doubts: ‘Do I deserve to be? Is that the question?’ Because he’s fucked up forever! So now he doesn’t know how to deal with it. So what does he do, he goes out killing people — that was [the song] ‘Once.’ He becomes a serial killer. And ‘Footsteps,’ the final song of the trilogy [it was released as a U.K. B side to ‘Jeremy’], that’s when he gets executed. That’s what happens. The Green River killer… and in San Diego, there was another prostitute killer down there. Somehow I related to that. I think that happens more than we know. It’s a modern way of dealing with a bad life.”

Then he smiles as he says, “I’m just glad I became a songwriter.”

Sitting next to Vedder, Ament listens like a fascinated brother. Perhaps he is remembering the first impressions Vedder made upon arriving in Seattle. Friends from his early days up north recall a different Vedder from today, a desperately shy surfer, a guy with a lot of heart and little irony. One friend even called him Holy Eddie. “He was genuinely quiet and loving Eddie when we first met him,” says Ament. In the band’s earliest shows, Vedder had been so self-effacing, he barely looked up. “And at a certain point, he changed.”

An early turning point came onstage at a club called Harpo’s, in Victoria, British Columbia. It was Pearl Jam’s maiden tour, their first appearance away from a nurturing audience of Seattle friends. But this Canadian crowd was far more interested in getting drunk. In midset, Vedder decided to challenge the jaded audience, to wake them up. Unscrewing the 12-pound steel base of the microphone stand, Vedder sent it flying over their heads, like a lethal Frisbee. The steel disk crashed into the wall of the back bar.

They woke up.

Vedder would never fully be the same. Gossard credits the influence of Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell, who had asked Vedder to sing on his tribute to Andrew Wood, Temple of the Dog. “Cornell had already transformed himself in an intense way,” Gossard says. “Eddie looked to him as a guide to help us through that time.”

Vedder soon developed a new stage habit. He began climbing the stage scaffolding or the wings of the theaters the band was playing, falling into the hands of an often worshipful crowd. “I think the first time I got really worried, we were in Texas,” recalls McCready. “Eddie climbed up on this girder, about 50 feet in the air. Nobody knew where he was. And all of a sudden you look up — some guy had a flashlight on him — and it was like ‘Fuck!’ He’s up there clinging to a girder. I’m thinking, ‘This guy is insane, but I’m so totally pumped.'”

“That whole thing almost turned into a circus event,” adds Ament. “People weren’t looking at his eyes when he was doing that. I think they were looking at the fucking freak, you know. The guy who was dumb enough to put his life on the line. Evel Knievel. But if you looked at his eyes, man, there was an intensity in what he was doing. That was his belief in himself. He was saying, ‘This isn’t just “rock” to me.'”

The band returned from a European tour and taped a stirring edition of Unplugged. There was a particularly galvanizing, unforgettable moment at the end of “Black.” “We belong… together… together,” Vedder sang. It was simple, a guy sitting on a stool, ripping his heart out, drowning emotionally, right there in front of you. After Unplugged, letters to the band’s Ten Club almost doubled, many were about “Black,” and they began in an eerily similar fashion: “I was recently considering suicide, and then I heard your music…”

Vedder answered many of the letters himself, sometimes leaving the band’s office in a wreck. But there was more work to be done. Almost immediately, the band returned to Europe to play some of the big summer festivals in front of 30,000 to 50,000 people. It was trial by fire.

“The whole thing culminated in Denmark,” says Ament. “The Danish, I think, were playing Italy in the World Cup, so the city was crazed. Nirvana was playing there, and they were dealing with their fame, too. We played the show in front of 70,000 people. Eddie went into the crowd, like he usually does, and he came back, and the security didn’t know who he was. They started beating him up. Half the band went down. This was during ‘Deep.’ I remember we stopped, and I was ready to jump down, seeing this total riot happen… and Eddie and Eric [Johnson, tour manager], they’re totally swinging. And Mike’s down there, and Dave’s down there.”

The previous night in Stockholm, Sweden, Vedder explains, the band had played a longer show than usual. A group of Americans had reportedly broken into the dressing room and, among other things, stolen Vedder’s lyrics and journals. He had intended to give them away at the end of the tour, just as he’d done on an earlier European visit (with a backpack personalized by handwritten accounts of each show). But the theft weighed on him; it felt like a breach of trust, a bad omen. For Vedder, it was a metaphor for the growing success of Pearl Jam. The band about which Ament had once written, “Add water, watch Pearl Jam grow,” was growing wildly, far beyond the small-scale plans for a small-scale debut. “It made us feel like playing those huge shows maybe wasn’t as important as we thought it was,” says Ament. “We packed our bags, and we left the next morning.”

Sitting in the Nightlite, Ament and Vedder recall the bruising end to that 1991 tour. The band had seen their unassuming debut album, Ten, sell into the millions. Only Billy Ray Cyrus had kept them from the No. 1 slot, thankfully saving at least one achievement for later. Pearl Jam had been designed for a slow build. Instead, they were strapped to the rocket. The band held numerous meetings: “Where do we draw the line?” The line was drawn at “Black.” Eddie Vedder refused to turn the song into a video, wouldn’t listen to the corporate coaching that told him the track was, as Vedder puts it, “bigger than ‘Jeremy’, bigger than you or me.” Vedder held firm, and the band backed him up.

“Some songs,” he says, “just aren’t meant to be played between Hit No. 2 and Hit No. 3. You start doing those things, you’ll crush it. That’s not why we wrote songs. We didn’t write to make hits. But those fragile songs get crushed by the business. I don’t want to be a part of it. I don’t think the band wants to be part of it.”

The subject soon turns to video, and Ament describes a recent encounter with Mark Eitzel from the group American Music Club. Ament and McCready jammed with the band in Seattle, but within 30 seconds of conversation, Eitzel took the opportunity to challenge Ament on the “Jeremy” video. “I liked your hit,” he’d told Ament, co-author of the song, “but the video sucked. It ruined my vision of the song.”

The exchange stuck with Ament. “Ten years from now,” he tells Vedder, ‘I don’t want people to remember our songs as videos.”

Vedder agrees. He promises that the new album will be released before any videos. “I don’t even have MTV,” he says with a shrug. “I don’t know why I’m commenting. People stop me in the streets and tell me about this band Stone Temple Pilots. I don’t even know who they are. I’m buying a sandwich, and they go, ‘What’s going on with the Stone Temple Pilots?'”

“You haven’t seen the video?” asks Ament. “You have to have seen it.”

“I haven’t,” he says. “I don’t have MTV.”

Ament tells Vedder about the “Plush” video, with the singer’s uncanny appropriation of Vedder’s mannerisms. Vedder’s heard it before. In fact, he hears it daily. From fans, from friends, even from a French musician who complimented him on the song and his new short orange hair. (Vedder’s hair is still longish and brown.)

“Apparently, it’s something that the guy is dealing with, too,” Vedder suggests. “It’s like, am I supposed to feel sympathy? Get your own trip, man. I don’t think I was copping anybody’s trip. I wasn’t copping Andy Wood’s trip. I wasn’t copping Kurt Cobain’s trip, even though Kurt Cobain’s one of the best trips I could ever cop. But Beth and I were part of the San Diego scene. We knew everything that was going on, and it was small enough to know. Those guys came from there? I never heard of ’em.” End of subject.

For several more hours, Vedder and Ament reminisce over the strange daze of the last few years. Vedder admits to Ament that it’s no longer as easy, the stage appearances are tougher now. It’s harder, he says, to gear up to sing the songs the way that they must be sung. And although Vedder is only an occasional drinker, he has taken to slugging at a bottle of red wine onstage. When the conversation turns to the late Andrew Wood, though, Vedder becomes reflective.

“I wonder about Andy,” he says. “I relate sometimes. Not the drug part — I don’t need drugs to make my life tragic — but the fact that things were going so well for him. He didn’t know.” Vedder pauses. “There’s one song of his that I’d be proud to sing. I won’t tell you which one. But there was one song of his that always got to me. Someday I’m going to sing it.”

Vedder excuses himself to visit the restroom. Ament shakes his head “First time I heard that,” he says with a private smile.

It’s 2am now, a chilly night in June. Ament and Vedder stand shivering on the corner outside the Moore Theater. Neither seems anxious for the night to end. Fingering their car keys, they continue talking under the darkened marquee. Tonight is Grad Night in Seattle. Last call barflies and late night prom couples brush past them on the street, no one recognizing the two musicians, save for one woozy grad in a crimson tuxedo. For a few minutes, he stands watching them from nearby, softly repeating a drunken mantra to himself. “Eddie, Eddie, Eddie, Eddie, Eddie,” he says and then moves on.

“I don’t know if it was the beer or the company or what,” Ament remarks, “but I got to a place tonight I hadn’t been in a long time.”

“Me, too,” says Vedder. “So much has changed around here.”

“There’s going to be a point where it’ll revert back to the way that it was,” says Ament. “We’ll get through this whole period right now. We’ll get back out there playing. We’ll get back to actually being five guys who want to work it out together.”

Vedder thrusts his hands deep into his pockets. “I’d really like that,” he says.

The two band mates stand in the dark for another 10 minutes, talking about Oliver Stone, about Reservoir Dogs, about attitudes in the band and sexism on the road, about their pride in the new songs and about Vedder’s ultimate meltdown plan. He can always sell solo cassettes out of his house for $1.50. Finally the cold overtakes them.

“See you tomorrow,” says Ament, heading for the parking lot across the street.

“Wait,” says Vedder, “I’ll go with you.”

* * * *

“Fuck you,” yells a chorus of fans near the front. There is little poetry in the Italian crowd. Forty thousand fill this Roman soccer stadium today, but there isn’t much they’re interested in seeing outside of the group on the ticket — U2.

“Fuck me?” repeats Vedder, out on the lip of the stage. “Tell you what — you fuck me, and Bono will fuck you!”

The band launches into “Even Flow” and attempts to build a consensus, good or bad, anything. The struggle for acceptance ends in a draw. This is one of the few countries in the world not to have fallen under the Pearl Jam spell and the band feels the chill in its first of two shows opening for U2’s Zooropa ’93 road extravaganza. It would be easy to write this audience off as lackadaisical, but within seconds of leaving the stage, the Zooropa DJ spins Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust,” and the entire stadium thunders along in beat, instantly.

Back in the dressing room, the band mills about, somberly picking at food. Abbruzzese already has a game plan for tomorrow: “I’m gonna lower the drum riser so I can see the audience. I’m gonna connect with those people.”

Within a few minutes, Vedder emerges upbeat and finds some American fans. “I wish we’d played a club here,” he tells them, signing some shirts. He and Beth Liebling head out to the mixing platform to watch U2 with the rest of the band. Before long, a cluster of super- and semi-supermodels position themselves just behind him, clucking and whooping, taking pictures, trying to get his attention. Vedder remains fixed on the spectacle ahead. Finally one of the models manages an introduction to him. She speaks earnestly to him, shaking his hand. Vedder nods politely, turning back to the show. Total time investment — three seconds.

Later the band rides the tour bus back to the hotel. Stuck in traffic, a crowd of Italian fans discovers the bus and strains to look inside. Their expression is unmistakable. “Oh,” they seem to say, “it’s the other band.” But still they stare, as if looking inside a fish-bowl. “Wish we’d played a club date here,” says Vedder to no one in particular.

The conversation turns to Neil Young and the upcoming show with him in Dublin, Ireland. The band is soon talking about its next chance to jam with Young on “Rockin’ in the Free World” But even this venerable topic is soon exhausted, and still the Roman faces stare inside the windows of the stalled bus. It’s unsettling. It is as if Zoo TV has gone off the air, and the test pattern is Pearl Jam.

Until about a month before its release, the album was going to be titled Five Against One. The name comes up during a meeting in a hotel room in Rome as the band approves the final mixes of the record. There are already rumblings from the record company. Can you raise Eddie’s vocals? And there is the issue of video. Can we get a decision on a director? And the press interviews. You gotta do some. The answers to the questions are Not really, No and Later. Decisions swirl around them hourly, but Pearl Jam are intent on doing it their own way. The album title feels appropriate. The phrase comes from a new song, “Animal.”

“For me, that title represented a lot of struggles that you go through trying to make a record,” says Gossard, who picked out the phrase. “Your own independence — your own soul — versus everybody else’s. In this band, and I think in rock in general the art of compromise is almost as important as the art of individual expression. You might have five great artists in the band, but if they can’t compromise and work together, you don’t have a great band. It might mean something completely different to Eddie. But when I heard that lyric, it made a lot of sense to me.”

It’s now Day 2 in Rome. Vedder sits at the top of the stadium bleachers on this blazingly hot afternoon in July. He wears a tourist shirt that says I x GRUNGE. He is rather anonymous in this country, and it agrees with him. “The whole success thing, I feel like everybody else in the band is a lot happier with it than me,” he says. “Happy-go-lucky. They kind of roll with it. They enjoy it, even. I can’t seem to do that. It’s not that I think I’m better than it. I don’t know. I’m just not that happy a person.” He shrugs. “I’m just not. What I enjoy is seeing music, getting to watch. Watching Neil Young. Or I get to watch Sonic Youth from the side of the stage. That’s what’s been nice for me. “Music is an incredibly powerful medium to deliver a story by. But the best thing is, you have to have volume. You’re supposed to play it loud. I would do anything to be around music. You don’t even have to pay me.”

Vedder confesses having some recent difficulties in writing for Pearl Jam. As Gossard had pointed out earlier, the other band members now call him their spokesperson, and with that comes a certain Eddie ethic. Vedder works hard with manager Kelly Curtis to keep ticket prices low and to police the powerful promotion machine of Sony Music. But therein lies the grand contradiction. The artists he most admires are the very ones who have turned their backs on the machinery of big-time rock — like Henry Rollins and Ian MacKaye of Fugazi.

And Vedder, the guy who never slept, still doesn’t sleep. “Never have,” he says. “Never have, and now I really don’t. I have that spasm thing. I wake up and go, ‘Aaarrrgh.’ I’ll get up and start pacing. I’ll walk through a room, and the TV’s on and my face is on, and I start to freak out. I want to call a friend and say, ‘Did I lose my mind? I need perspective.’ I talked with Henry Rollins one day. I said, ‘Dude, I need some perspective real quick.’ And I really felt bad doing it. Because I was calling him up for the same reason kids call me up.”

You wonder, of course, if this is all part of Vedder’s elaborate defense mechanism. How can you attack the man who attacks himself? How can you doubt the credibility of a man who won an MTV Video Award for “Jeremy” and then told 50 million viewers, “If it wasn’t for music, I would have shot myself in front of that classroom.” For all his open-wound honesty, there are many mysteries that Vedder still clings to. Even a close band mate like McCready says: “No, I don’t know if we’ve ever had that big, bonding talk yet. Our relationship is still growing. We’ll probably have it sometime soon.”

Asked about his childhood, Vedder plays it close to his chest. He tells an anecdote about waiting tables back in Chicago. He tells of moving to San Diego and buying beanbag chairs and his first bad stereo. He tells of bootlegging shows, something he still does with a pocket-size microrecorder. All perfect sound bites for populist myth making, but when confronted with questions about his childhood, Vedder becomes vague. Of his earliest memories, he says only, “I’m confused. I’m mixed up about everything. I don’t know what’s happening now.”

He still answers fan mail, though less frequently, and tour manager Eric Johnson sometimes visits the Seattle office late at night to find Vedder calling back troubled fans. But as Vedder had carefully told one fan in San Francisco after a show: “I’m really not in your head, I’m not thinking all your private thoughts.” The fan had looked so disappointed. Vedder, in turn, has learned the public effect of writing well about damaged personalities.

“I was surprised and a little upset that so many people did relate,” says Vedder. “Everyone’s fucked up. Actually, now I understand those religious channels more. Everybody needs something.” He pauses for a long time. “There should be no messiahs in music. The music itself, the music, I don’t mind worshiping that. I’ve done that. And with that comes a little bit of admiration for the people who make it — or awe or whatever — but I never asked for nose hair from Pete Townshend.”

Back in Rome, on the second day, Pearl Jam offer a combative performance. “I’ll meet you back here at a club next time,” Vedder says, to sprinkled applause. Later, he begins to goad them, telling them their stadium was built for soccer, not music. And below a neon Zoo TV sign, he playfully taunts further, “Are we animals?” Let it never be said that Vedder doesn’t enjoy the fine taste of the hand feeding him. His green T-shirt contains today’s gaffer-taped message: PAUL IS DEAD. (Look up Bono’s real name.) The set closes with Vedder donning a huge fly mask, dancing as if caught in a web. It is Pearl Jam’s own lo-fi answer to Zoo TV. Not many fans here get it, but one who does is Bono, who watches curiously from the pit.

Bono responds later that night, onstage. “So you can’t play music in a soccer stadium,” he muses. “Well, if you do, it better be good music…” But before the set is over, he hails Pearl Jam as “a great rock & roll band” And Vedder, Liebling and Ament will stay up all night with Bono and the Edge, talking passionately in a diner, debating the issue of the day, the emotional exchange rate on success. And at 6am, there are Vedder and Ament exchanging hugs with Bono on an empty Roman street, arriving at the bus just in time for the trip to Dublin.

“I got all my questions answered,” Ament confides. In the course of the dates with U2, he had discussed the hugeness vs. purity issue with all four members of that band. “And they basically told us this: ‘We used to be like you. We used to be anti-anti… We used to be angry. But we love technology, like you love what you love. Next tour we might only play 3,000-seat halls. But this is where we are today. Ten years from now, you tell us where you are.'”

Today In Dublin, the day before Pearl Jam play before an estimated 50,000 at nearby Slane Castle, Abbruzzese stands and watches as thirty or so young Dubliners sing resolutely to street-busking versions of “Black” and “State of Love and Trust.” Abbruzzese is grinning, handing out flowers on Grafton Street, playing with street kids. “Gone is the bleachy sunshine of Italy. In its place is rain… pale faces… romantic beery arguments in the street… it feels like home.

Elsewhere, there are rumors that McCready has fallen off the wagon, running naked through the streets of Dublin late the night before. McCready, shopping for bootleg tapes today, does not confirm or deny this behind his reflector shades. “I love this place,” he says.

Backstage the next day at the show, there are few of the trappings of big-time rock. No open bar, no stereo rack pumping psych-up music, no bodyguards, no supermodels. Just Vedder talking about why he couldn’t care less.

“I’m embarrassed for some of the ‘veterans’ of music,” he says. “They had their original [macho] image, and they’re still hanging on to it. The sex thing, they’re still working it. This-dude-looks-like-your-grandpa kind of thing — it’s so silly, it kinda makes you sick. These guys are still using the ancient version of what’s sexy, the bikinis and tongues. It’s over. I relate to the people that are coming up now, and that’s not there. That’s long gone.”

Vedder’s relationship with Liebling, a writer, is the strongest one in his life. They’ve been together nine years. Perhaps soon, he says, they’ll be married. And when it’s time to start a family, he predicts he’ll be a devoted parent. He cites Michael Jordan’s father, then still alive, as a perfect example. “The ultimate parent is if they’ve made a decision to have kids, that means they’re going to give someone else a chance, and they’re going to do whatever they can to boost that kid up so he can really shine,” he says. “I feel like, in the last 20 years, that’s been drained out of parenthood. I’m into real life. I’m into getting the most out of real life.”

Sitting now in the shadow of the 200-year-old Slane Castle, the hazy sun shining on his face, Vedder is asked about his own youth. What about his father?

“I never knew my real dad,” he says. “I had another father that I didn’t get along with, a guy I thought was my father. There were fights and bad, bad scenes. I was kind of on my own at a pretty young age. I never finished high school.”

He was Eddie Mueller then. After moving briefly to San Diego, both his parents had returned to Chicago. Vedder, who subsequently took his mother’s maiden name, had stayed behind to pursue his career in music. There was a rough goodbye to his stepfather. They haven’t spoken since. Later, Vedder was living in San Diego when his mother visited from Chicago with some important news for him.

“She came out with the specific purpose,” he says, “to tell me that this guy wasn’t my father. I remember at the time I was like ‘I know he’s not my father, he’s a fucking asshole.’ And she said, ‘Oh, Eddie, he’s really not your father.'”

“At first I was pretty happy about it, then she told me who my real dad was. I had met the guy three or four times, he was a friend of the family, kind of a distant friend. He died of multiple sclerosis. So when I met him, he was in the hospital. He had crutches, or maybe he was in a wheelchair.”

Vedder plays with his ripped-out shoe. Somehow, a half-world away, the words flow easily as he recalls, as he puts it, “the day I found out.”

“There was a piano in the room,” he goes on, “and I remember really wishing I knew how to play a happy song. I was happy for about a minute, and then I came down. I had to deal with the fact that he was dead. My real father was not on this earth. I had to deal with the anger of not being told sooner, not being told while he was alive. I was a big secret. Secrets are bad news. Secrets about adoption, any of that stuff. It’s got to come out, don’t keep it. It just gets bigger and darker and deeper and uglier and messy.

“Musically, I tried to think if I had a goal, what it was, and I think more than anything it was to leave something for my kid, if I had one to listen to. I’m actually a junior. My real name is something-something the third.” Fans can find it in the song credits to “Alive,” on Ten.

Vedder’s biological father, it turned out, was a musician himself, an organist-vocalist who sang in restaurants. Once Vedder knew the truth about his heritage, other relatives stepped forward.

“There were all these things they wanted to say,” he recalls, “like ‘That’s where you got musical talent,’ and I was like ‘Fuck you.’ At the time, I was 14 or 15, I didn’t even know what the fuck was going on. I learned how to play guitar, saved all my money for equipment, and you’re telling me that’s where it came from? Some fucking broken-down old lounge act? Fuck you.”

Vedder says this quietly, but time has barely mellowed his emotions. It’s no surprise that Quadrophenia, The Who’s 1973 classic tale of disaffected English youth, was Vedder’s Catcher in the Rye. (He once told an interviewer, “I should be sending Pete Townshend cards for Father’s Day.”) Music saved his life, he says, but the turbulence of Vedder’s youth still fuels the music. It’s a painful circle. “My folks are very proud of me now,” he says, “and again, I’m thankful that they’ve given me a lifetime’s worth of material to write about.”

(Recently, a meeting with his real father’s cousin left Vedder with a sense of closure. “The strange thing,” he says, “is that there are so many similarities between my father and I. He had no impact on my life, but here I am. I look just like him. People in my family — they can’t help it — they look at me like I’m a replacement. That’s where ‘Alive’ comes in.” He pauses. “But I’m proud of the guy now. I appreciate my heritage. I have a very deep feeling for him in my heart.”)

Have fun with it. You hear the phrase often around Vedder. He rarely has a response. Have fun with it. Certainly, his rock dreams are coming true: to sing “Masters of War” at the Bob Dylan tribute concert last year, to sing with The Doors at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and to finally meet his hero Pete Townshend. But to have fun with it, it seems, would put him one step closer to those rock stars in the magazines, the ones flipping their hair, the ones who caused him to write Pearl Jam’s defining statement in “Blood” — “It’s my bloooood.”

It’s way too late to be Fugazi, and Vedder knows it. Still, Pearl Jam offer fans a challenge: Bootleg us if you can, take our album, pass the music around, don’t glorify us. Vedder long ago traded away the brown thrift-store jacket given to him by Gossard, the one remade and marketed by the fashion industry as a $1000 piece of grunge wear. The band no longer condones stage diving for safety reasons, and even Vedder’s scaffold climbing appears to be history. He offers an interesting perspective:

“That climbing happened out of me saying ‘Look this is how extreme I feel about this situation. This is how fucking intense I’m taking this moment.’ You can’t do that for long, because what they really want to see is, they want you to chop your fucking arm off, hold up your arm, wave it around spewing blood, and believe me, if you did that, the crowd would go fucking ballistic. You only get four good shows like that, though. Four good shows, and then you’re just a torso and a head, trying to get one of your band mates to give you one last hurrah and chop your head off. Which they probably wouldn’t do, which would really be hell.

“But,” Vedder says with a laugh, “they’d say, ‘Sing from your diaphragm, at least you still have that going for you.'”

The Dublin audience is fiercely awake, fueled by anger and ale. Van Morrison performs to the hometown crowd, and he is greeted like a beloved uncle. He is offstage only a few minutes before the audience, in anticipation of Pearl Jam, surges to the front. “I love some kind of pressure in the air,” says McCready, peering out at the boiling mass of Irish fans. “Some kind of weirdness in the crowd, good or bad. That’s what we thrive on.”

Pearl Jam take the stage, and the crowd packs closer, straining the barriers. It’s brutal down in front, and security is already pulling the semiconscious out one by one, before a note is even played. Vedder walks on in a gorilla mask, pulls it off and hurls himself into “Why Go.”

It is a crowd happily perched on the edge of danger and today they get the best out of Pearl Jam. Onstage, the band is narrowly missing each other as they all, in different ways, leap for joy, pogoing and twirling, just missing each other’s skulls with the instruments. The volatile crowd does not scare Vedder; he’s seriously singing to those serious faces listening to him the way he listened to The Who — with their whole lives attached. He stands on the edge of the stage, just watching them, and turns to share it with Liebling, who catches it all on Super 8.

It’s the show they’ve been waiting for, a glimpse of the future. “If it all ends tomorrow,” Abbruzzese says, “I will be the happiest fucking gas-station attendant you ever saw.”

Best of all, Pearl Jam are no longer a band with only one very, very big album to their credit. “There’s no school to go to for some of the weird shit that happens,” says Vedder. “The fucking weirdness of it all. But some of these guys, they can help out a bit. Bob Dylan’s advice was ‘Go to Dublin.’ I wrote him a postcard today.”

“It said, ‘Made it.'”

Courtesy of Rolling Stone #668 – Cameron Crowe – October 28, 1993