Elizabethtown – Entertainment Weekly

Kentucky Fried Movie

After lackluster festival reviews, director Cameron Crowe scrambles to get his heartfelt romantic comedy ”Elizabethtown” in shape for general audiences. Will they show him the money?

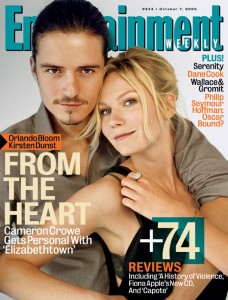

Cameron Crowe is having a quintessentially Cameron Crowe moment. If he had written it himself, an Elton John song might be playing over the scene and you, the fired-up audience member, would suddenly be singing along under your breath, rooting for the shaggy underdog to survive the firestorm that has engulfed his world, turning his life from comedy to high-stakes drama without his consent. In typical Crowe fashion, his rescue would probably come in the form of a soulful, beautiful woman with great taste in music who shows up with just enough good humor and good sense to remind him why he loves his life and that none of that other stuff matters. It’s been a rough week for Crowe, 48, who recently screened his new movie, Elizabethtown, at the Toronto film festival, and watched critics have at it like a piñata. Crowe, a best-screenplay Oscar winner for Almost Famous, has been a critics’ pet ever since he made his directorial debut with Say Anything… in 1989; which may be why he felt confident enough to take the risky step of entering the festival with an unfinished cut. His much-anticipated wistful black comedy follows a shoe designer (Orlando Bloom) whose professional fall from grace is cushioned by a new romance with an eccentric stewardess (Kirsten Dunst) and a reconnection with his Kentucky roots following his father’s death. But reviewers at Toronto reacted with something close to outrage, complaining the film was manipulative instead of moving, cloying instead of charming.

There are two gods whom filmmakers aim to please: critics and audiences. Having faltered with one, Crowe is now counting on regular moviegoers for redemption. Even before he hit the festival circuit, Crowe had begun assembling an alternate, shorter cut of the movie, just in case the longer one didn’t play. Now, he has his work cut out for him, with only three weeks to whittle his 135-minute Toronto version into the kind of tight, emotionally resonant crowd-pleaser his fans have come to expect. But even though Crowe is confident he’ll be able to iron out the wrinkles, the sting of bad reviews lingers, especially with a film as nakedly personal as this one, which was inspired by Crowe’s experiences in Elizabethtown, Ky., after his own father’s death in 1989.

Today, Crowe is peering out the front windshield of an Almost Famous-style rock & roll tour bus. He’s making another pilgrimage to Elizabethtown, where he’s come to premiere the eponymous movie he shot here last summer. He’s excited and a bit nervous as a police escort of four squad cars form a caravan leading him into town.

Crowe’s eyes widen as a crowd of hundreds appears on the roadside, waving homemade signs and cheering his arrival. (Cue Sir Elton.) There’s a guy holding a boom box above his head paying tribute to John Cusack’s lovelorn serenade in Say Anything…. Two middle-aged women display a banner saying ”Show me the movie!” Then there’s the teenage girl with a glittery poster bearing the Almost Famous catchphrase: ”It’s All Happening! Thank You, Cameron.”

For what seems like miles, diehards of all shapes and sizes line the rainy streets to hail Crowe for speaking to them in ways entirely personal to each of them. How else to explain a droopy-lidded man standing in the rain with a tiny, weeks-old infant tucked into the crook of his tattooed arm, holding an Elizabethtown poster in his free hand, and wearing a T-shirt proclaiming ”BEER: Helping ugly people have sex since 1862.” Crowe, clearly stirred by the outpouring, turns to face his wife (and Elizabethtown’s composer), Nancy Wilson, from the band Heart, who came along for moral support. ”Well, I’m glad you’re here,” he says with a slight strain of melancholy, ”so it’s [proof] that it’s actually real.”

For many moviegoers, Crowe is the guy who defined first love (Say Anything…), the grunge generation (Singles), what it means to be a man (Jerry Maguire), and the lonely heart of rock & roll (Almost Famous). They’ll forgive him a misfire on Vanilla Sky, a misguided detour into darkness that ill suited his sunny sensibility. But now it’s time to deliver the goods, and expectations are primed for Elizabethtown, Crowe’s return to what he does best: young love and personal reinvention.

Crowe is one of the few writer-directors making idiosyncratic, personal movies within the mainstream studio system, and he can scarcely afford another flop after 2001’s Vanilla Sky underperformed at the box office ($101 million is actually peanuts for a Tom Cruise movie) and failed to deliver his usual rhapsodic reviews. He is a true Hollywood anomaly in that he has steadfastly resisted all temptation to make a quick buck as a director- or writer-for-hire in between his personal movies, à la Steven Soderbergh. Crowe tells stories that come from the inside out, turning his preoccupations and life experiences into modern folk tales. Still, after a summer where Hollywood sent out a desperate APB for more original filmmaking, even brand-name directors like Crowe only get so many strikes. And after the screening at Toronto, where Elizabethtown went from festivalgoers’ must-see list to the not-for-me or, at best, the wait-and-see list, the onus is now on Crowe to make sure Elizabethtown fills theaters and leaves the door open to a future full of the movies only he can make.

No stranger to doomsday predictions, Crowe takes solace in his experience with films that have prevailed over a din of bad buzz. ”With Fast Times [at Ridgemont High], they didn’t want to put the movie out and it tested really poorly,” says Crowe, who made his screenwriting debut with the teen sex comedy directed by Amy Heckerling. He was similarly vindicated when he later released a longer director’s cut of Almost Famous on DVD to high praise after the studio-mandated shorter cut generated lackluster box office. ”It was very similar [to Elizabethtown]. Many things I’ve written have had a tough little curve.”

The illusions of success and failure and the precarious line that separates them have become recurring themes for Crowe both on screen and off. It’s no wonder, considering he soared to the top of the magazine journalism world at the tender age of 16, writing cover stories for Rolling Stone, and has occupied the upper echelons of moviemaking ever since Say Anything…. So it’s probably no accident that both Jerry Maguire and Elizabethtown revolve around characters whose thriving careers face sudden death. Even Say Anything…’s Lloyd Dobler was defined by his failure to have any ambitions beyond love and, similarly, Singles’ Steve Dunne (Campbell Scott) became a depressed shut-in when his work project was nixed by the mayor. It’s almost as if his movies are anxiety dreams with happy endings, writ large.

Back on the bus en route to the theater, Crowe has fallen under the spell of the lush, neon-green Kentucky countryside, which inspired the movie in the first place. ”Nancy was on tour [with Heart] and I woke up one morning and it was like this outside the window,” he says. ”And I said, ‘I have to rent a car and drive around.’ That’s where the whole movie came from…. My dad was stationed at Fort Knox nearby and this is the route he would drive into town.” For Crowe — or any guy, really — writing about his feelings for his father was the emotional equivalent of touching the third rail. Even today, he’s still tentative about copping to the script’s personal origins. ”I could have just as easily said, ‘I made the story up,”’ he admits, as if that temptation is still with him right now. ”But I figured, f— it. Tell the story of where it came from, because wouldn’t my dad love this movie that’s largely about his state and the feelings we had?”

In some respects, the film almost plays like a mixtape of moments — some new, some culled from his other movies. When Bloom’s bottomed-out shoe designer immerses himself in the seemingly alien world of his long-lost Kentucky relatives planning for his father’s funeral, he is able to reconnect with the most alive parts of himself and the memory of his father. Dunst’s stewardess is an effervescent free spirit, hell-bent on healing Bloom’s ailing heart even while hers could use some mending itself. Surrounding them is a menagerie of kooky lost souls that includes Susan Sarandon as Bloom’s mother in denial of the death of her husband.

Since the male lead would essentially be playing Crowe in his mid-20s, the writer-director struggled to find an actor who could balance the pain of losing a parent with comedy. Though he had first shown the script to Bloom, with whom he’d made a Gap commercial and become pen pals, each sending the other music and postcards over the years, he ended up initially casting Ashton Kutcher because of Bloom’s scheduling conflicts. ”I had a bunch of work sessions with Ashton and then the work sessions started to end on a slightly less high-fiving note,” Crowe says, carefully. ”It wasn’t quite jelling.”

Kutcher soon left the project, and by that time, Bloom was available. From the moment he stepped into the role, Bloom was keenly aware he had entered into unfamiliar territory. ”This was the first time where I was playing a real guy, a real character in a real experience. I wanted to do a contemporary movie, because I started getting the sense that people thought I was a one-trick pony,” The Lord of the Rings star says, doubled over with exhaustion in a Kentucky hotel room after pulling an all-nighter on the set of Pirates 2 and 3 and flying in for the premiere. ”I felt so proud to be in a movie that was trying to take a risk. Not everyone will necessarily… It might fly over some people’s heads or nail them right in the heart.”

The experience has made Bloom sanguine about his attitude toward his own future in Hollywood. ”It’s bizarre to me that Kingdom of Heaven could open at number one, make over $200 million worldwide, and still be considered a failure,” says Bloom of the expensive, much-anticipated 2005 summer epic whose domestic box office fizzled out at a disappointing $47 million. ”Now I think that’s actually really cool because for me, it’s part of the process. That’s what gets you the scars, those fights. It’s a notch here, a notch there, and it becomes some sort of life in itself. You [just] don’t want to shrink from it.”

Dunst, who first impressed Crowe when she was a runner-up for Kate Hudson’s role in Almost Famous, felt an immediate kinship with her character. She was cast early, after a typical Crowe audition, in which he played the music he’d picked out for the film to see how she responded to it and, more important, how the music sounded played against her image in close-up. ”You have this video camera in your face and I would react to different songs he would play,” recalls Dunst, who rarely auditions but agreed because of Crowe’s indelible female characters. ”Cameron wrote a beautiful role. She’s messy, wise, and sad. And the words came easily to me.”

While shooting, Crowe played music to help the actors access the characters’ emotions. It’s a technique the director hit upon courtesy of Tom Cruise. ”We were doing the scene where Jerry Maguire’s writing the mission statement and I started playing this song by His Name Is Alive and Tom was like, ‘Keep it playing!’ and he acted to the song and it was great,” recalls Crowe, who appointed his assistant to be the on-set DJ, playing mostly Jeff Buckley and Simon and Garfunkel for Bloom, and Rilo Kiley and Rufus Wainwright for Dunst. Still, there are risks involved: Play the wrong song and the mood is dead. ”Kirsten came hard with her own opinions on what should be playing,” Crowe says. ”I put on the Monkees and Kirsten just stopped and said, ‘I can’t do this.’ She’s a really hardcore music fan so sometimes it felt like being her DJ.”

Though Crowe puts on a brave face and says he doesn’t give much power to Elizabethtown’s naysayers, he reveals flashes of vulnerability when defending his movie as if it were his child who just got beat up after school. ”This movie is definitely a populist film, not created for cynics,” says the director, who insists that non-industry audiences have responded positively in test screenings. ”It’s the nature of this one that it’s tough to get all the pieces right…. And you saying something is a ‘work-in-progress’ is like handing everybody a red pencil and saying, ‘What are your notes?”’

Even after Toronto, Paramount, the studio releasing Elizabethtown, has refrained from the usual panicked meddling. ”Reviews are what they are. You live with them, hopefully learn from them, and move on,” says Gail Berman, president of Paramount Pictures. ”We’re on the same message since we began. The populist reaction to the movie is overwhelming. We’re going on this journey with [Crowe] and believing in this process.” In other words, Crowe has final cut.

In the new version, Crowe says he’s honing the focus on Bloom’s character and trimming the memorial scene, in which Sarandon’s character busts out with an odd stand-up comedy routine. ”It’s going to be 18 minutes shorter,” he says. ”I cut down a lot of the goodbyes toward the end. There were two choices about how to do the movie: as a double or a long single CD. The way it was shot suggested you could make it more of a spell-creating experience [where] you go through some of this stuff almost in real time.”

Crowe, a self-described ”warrior for optimism,” continues to battle what feels to him like an encroaching tide of cynicism, insisting that moviegoers, the real people, have got his back. His bus arrives at the theater and he is greeted by three little girls holding a banner that says ”Welcome Back to E-Town. Small town. Big heart. Just like you!” He smiles and waves. For now, at least, his instincts are confirmed: This is humanity putting its best foot forward. The besieged protagonist of this story has found the warm embrace of an audience primed to love his movie, right here where it was born when he came to say goodbye to his father for the final time 16 years ago. ”I like that someone might come up to me and say, ‘Did the father die to save his son’s life?’ It sure beats sitting around in a room with buddies, going, ‘How do we do the heist movie for the millionth time?”’ Crowe says, before stepping off the bus. ”This movie chose me. And if it works out that I get slaughtered for a movie that came from my heart, I can live with myself.”

Courtesy of EW – Christine Spines – September 30, 2005