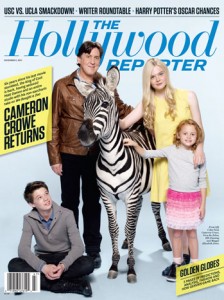

We Bought A Zoo – Hollywood Reporter

Cameron Crowe Returns

One movie tanked, another went off the rails, his marriage foundered. But after six years, the director is back with “We Bought a Zoo,” and once again he used rock ‘n’ roll to get his way.

When Cameron Crowe was courting Matt Damon to star in We Bought a Zoo, he traveled to the set of the Coen brothers’ True Grit in Austin and presented Damon with a script, a CD of songs that he’d burned and a copy of Local Hero — a perfect little 1983 movie in which Peter Riegert played an oil-company executive sent to buy a remote village in Scotland.

“My instructions were to not just read the script and make a decision,” Damon says.

Crowe had brought all the tools in his kit — music, film and words — not only to convey what he had in mind for this movie but to envelop Damon in the world he meant to create. “He said: ‘I know what you’re going to be afraid of; the bad version of this movie is really a movie you don’t want to be in. That’s what I’m afraid of too,’ ” Damon says. And that told Damon two things: that Crowe wanted to avoid making the bad movie and that he intended to fight against it with Damon as his brother-in-arms.

Crowe was right: Damon didn’t want to make what he calls “the Disney version” of the story about a grieving widower with two children who makes the unlikely decision to buy and restore a dilapidated zoo. “It might be popular, but it wouldn’t be something that I’d be proud to be a part of,” Damon says.

As he listened to Crowe’s music on a run through Central Park, though, he got a very different vibe. “There were all these songs I know but live versions that he got from sound boards,” Damon says. “A song like, ‘I’m Open’ by Eddie Vedder — he gave me a particularly moving version that I’ve never heard. I kind of finished that run and went, ‘That’s a really good feeling.’ ”

Then Damon watched Local Hero and found it to be “a masterpiece.”

Still, Crowe, 54, hadn’t directed a feature since the poorly received Elizabethtown in 2005. Damon says he wasn’t thinking about that film but rather about Crowe’s 1996 hitJerry Maguire. “I kept coming back to, this is the guy who did, ‘You complete me,’ ” Damon says. “This is a guy who could aim for that small bull’s-eye and hit it.”

So he signed on to do We Bought a Zoo, happily succumbing like many before him to the delights of a Cameron Crowe seduction.

As for Crowe, he says it was the other way around. Fox was imagining a shortlist of candidates for the lead, but Crowe says it was all over for him halfway through his meeting with Damon. What lured him was the actor’s obvious appetite to play the emotion in the film.

“He’s, like, wide open to a thrilling new peak and searching for it,” Crowe says. “There’s nothing, ‘Kid, this is how we did it with Clint’ about it.” So “it was purely him seducing me because halfway through our meeting, I was like, ‘I can’t do this without Matt Damon.’ And I declared it.”

♦♦♦♦♦

We Bought a Zoo is a movie that defies easy categorization, so it might seem an unlikely project to come from Fox, which has not established a reputation for taking creative risks (unless you happen to be James Cameron). Damon plays the father who buys the zoo to begin an adventure and console his motherless children. Scarlett Johansson is the scrappy zookeeper. The film is a comedy and a drama; Tom Rothman, co-chairman and CEO of Fox Filmed Entertainment, calls it “an emotional event” and says no one should be surprised that the studio backed the project. (The film opens Dec. 23, but Fox is so high on it that the studio scheduled sneaks around the country during Thanksgiving weekend hoping to generate strong word-of-mouth.)

“We do a lot of things around here that don’t fit neatly into a niche, and this movie was one of them,” Rothman says. “That’s what’s kind of great about it. You say, ‘What movie does this remind you of?’ and no one can give you a movie.”

That’s why many in the industry say they are rooting for Zoo even if they have nothing to do with the film. “Cameron works from a truly, deeply creative place,” says Paula Wagner, a producer on Crowe’s Vanilla Sky (2001) and Elizabethtown. “And I don’t know that our business right now allows that. Our business became very focused on the business of it all. The buzzwords became about numbers, brands. But the word ‘original’ is coming back into our vocabulary. That’s what I would say about Cameron: original, original, original.”

Says Crowe’s former mentor, James L. Brooks: “He’s singular — that’s the big deal about Cameron. There’s one guy like that.”

Crowe was never a director to crank out one film after another: There were generally gaps of about four years from Say Anything (1989) to Singles (1992) to Jerry Maguire (1996) to Almost Famous (2000). But with a longer break than usual, it has been natural for some of Crowe’s old associates in the industry to surmise that he had not made a film since 2005 because of disappointment. His 14-year marriage to Nancy Wilson of the rock band Heart ended in divorce in 2010. And Elizabethtown, a $45 million film pairing Kirsten Dunst and Orlando Bloom, had fizzled at the box office and brought unaccustomed wrath from critics.

Crowe had taken some knocks for Vanilla Sky, his adaptation of the Spanish film Open Your Eyes, but the long knives really came out for Elizabethtown. The Village Voice panned it under the headline “Almost Shameless,” while The New York Times dismissed it as “a strange, messy stew of a movie.”

But Crowe seems baffled and a bit dismayed by the supposition that he was in a funk or somehow affected by the chilly reception of his most recent film. “Elizabethtown was a movie made for all the right reasons, and people who connect with the movie really connect to it,” he says. “It’s not the biggest group of people ever, but I still really believe in Elizabethtown. It wasn’t, like, a savage blow.”

Instead, Crowe says he simply got engaged in writing scripts, including a long and ultimately frustrating effort to make a Marvin Gaye biopic with Will Smith. “We had many meetings where we talked about it,” Crowe says. “And at the end, he couldn’t say yes. It’s a tough thing to play Marvin Gaye. He’s a towering figure. … Who would want to be the guy who played Marvin and didn’t nail it? Will isn’t wrong; the guy who plays it should be a guy who tears into it and knows it’s the right thing, and I don’t think he ever came around the corner on it.”

While working on that and other ideas — and hanging out with his twin boys, now 11 — Crowe says, “I got into such a script-writing mode that I lost sight of the joy of directing.” Then Fox production president Emma Watts came to him with a draft for We Bought a Zoo by Aline Brosh McKenna (27 Dresses, The Devil Wears Prada). The script was based on the 2008 book by Benjamin Mee, the man who actually bought the zoo. Watts found herself pitching the project to Crowe on her phone in the Neiman Marcus parking lot, and she says her hopes weren’t high. After all, Crowe had written pretty much every film he had directed, and most felt very personal to him. “I don’t get nervous very often, but I actually did,” she says. “I thought for sure I was dead because he was being so polite to me.”

But Watts was thrilled when Crowe said he would try a rewrite to see if he could find his version of the movie. “There’s nothing quite like a turn through his typewriter,” Watts says. There are so many lines from Crowe movies that stick in the popular psyche: “You complete me.” “You had me at hello.” “Show me the money.” “The guy just writes lines that you think of your whole life,” Watts says.

“I knew talking on the phone to Emma that Benjamin Mee’s real-life story had all the elements I love in storytelling: humor, great characters, love and an impossible dream,” Crowe says. “I could already hear the music too. … That story came knocking in a big way, and it didn’t go away. You wait for the zing, and the zing happened on We Bought a Zoo.”

♦♦♦♦♦

Crowe’s website is called The Uncool, which is funny, of course, because Crowe has been the King of Cool for a generation that believes it really knows cool. His gift for making those around him feel included in his cool world is part of his magic. “I was incredibly susceptible to that because I was never cool,” says one executive who has worked with Crowe. It’s a quote that could come from many in Hollywood.

Crowe came by his cool honestly. He was born in Palm Springs to a realtor father and a mother who taught English and sociology, demonstrated for peace and farm-workers’ rights and recognized that her son was gifted. Crowe skipped kindergarten and two grades in elementary school. “It wasn’t that I was a tiger mom and wanted to push my son,” says his mother, Alice, now 90. “He was sort of bored.”

By the time he was in high school in San Diego, he was very obviously younger than his classmates, and he was battling a kidney disease, nephritis, which Crowe says he eventually outgrew. Crowe’s mother says he was so out of place that he felt more secure hanging out in the school’s newspaper offices. Crowe says the kidney condition gave him “permission to be a geek. …You’re weak, you go the doctors’ offices a lot, and you’re not on the teams at school so much. All of that opened the door for the arts because my mom was like, ‘I’m taking you to the movies.’ ”

If he felt uncool then, that didn’t last long. At 13, Crowe started writing rock reviews for a local alternative paper, The San Diego Door, even though his parents didn’t allow rock music in the house. (“I wasn’t that strict,” his mother says. “It’s just the lyrics bothered me. I thought they were very demeaning to women, especially.”)

The rest, as they say, is history. Crowe started corresponding with Lester Bangs, who had left theDoor to become editor of the rock magazine Creem. Crowe graduated from high school at 15 and on a trip to L.A., met Rolling Stone editor Ben Fong-Torres, who made him the youngest correspondent ever at the magazine. Crowe went on the road with the Allman Brothers Band at 18, and his work profiling such legendary rockers as Eric Clapton, Neil Young and members of Led Zeppelin not only enveloped him in permafrost cool but became fodder for Almost Famous. His mother’s dream — that he would go to law school, or even college — was doomed.

On an assignment on the set of the 1978 movie American Hot Wax, Crowe met producer Art Linson, who gave him a tiny cameo in the film. (“Whoever was there got to walk in,” Linson says.) The following year, Crowe enrolled in Clairemont High School in San Diego as a young-looking 22-year-old and wrote the book Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Linson optioned it before it was published. Crowe wrote the screenplay, and Amy Heckerling directed the film, which featured a cast of unknowns including Sean Penn, Jennifer Jason Leigh and Nicolas Cage (credited as Nicolas Coppola). The film was not only a sleeper hit, grossing $27.1 million, but became a pop culture touchstone.

“It was Cameron’s voice,” says Linson. “Half the things that were said out of people’s mouths in that movie are part of the culture. Cameron has a wonderful ear. He listens and he’s smart, so the details you hear are authentic.”

Crowe next teamed up with Brooks, who first produced Say Anything, in which John Cusack courted Ione Skye. He then drove Crowe hard through many rewrites of Jerry Maguire. “He’s somebody who was successful at a weirdly young age,” says Brooks. “He was successful in an amazing era when it was happening in the big time. There’s an enormous sophistication to that, but he never became cynical.” Crowe is “as sharp an observer as there is,” Brooks continues, but “his heart is still true. His emotion is genuine. … He loves all his characters.”

Crowe says Brooks — who made him write out the manifesto that Tom Cruise’s character announces, but never reads, in Jerry Maguire — taught him to be even truer to his own voice. The film was not only Crowe’s biggest commercial hit, with a gross of $274 million worldwide, but led to a close friendship and partnership with Cruise, who was a producer on Vanilla Sky andElizabethtown.

Throughout his career, Crowe has seemed to operate on executives and producers almost like a drug. John Goldwyn, who was president of Paramount when Crowe made Vanilla Sky there, says the filmmaker’s charm is unsurpassed. “There’s nothing aggressive about him, nothing that makes you bristle,” he says. “He makes you his friend. You can see why he was such a seductive interviewer.”

Says an executive who oversaw one of Crowe’s films: “I really can’t describe how he makes you feel that you can’t question his choices. He is charming, cool, warm — and you let down your guard as the boss.” That paved the way for Crowe to make his particular brand of personal movie, some with budgets that seem surprisingly big, especially in retrospect: $60 million for Almost Famous, $68 million for Vanilla Sky (though that one included Cruise in his heyday), $45 million for Elizabethtown (with no big star).

“Cameron doesn’t want to hear that something can’t happen exactly the way he’d like it to happen,” says a producer who has worked with him. “That’s why some of his movies have been overpriced. There’s a way to look at that as uncompromising. The other way to look at it is being a brat.” (In the case of We Bought a Zoo, Watts says Crowe came in under budget — at about $50 million — and ahead of schedule. And Rothman says the production “was one of the easiest and sweetest experiences I’ve had in a long time.”)

One area where Crowe very much wants his way is when it comes to preparation. Before shootingZoo, he rented space in the Hyatt Westlake Plaza in the San Fernando Valley to plan and rehearse. He taped off areas that were the same size as rooms would be on the set and even brought in furniture. Crowe and cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto blocked scenes, the cast rehearsed, and Damon says by the time the cameras were rolling, “It felt like executing a game plan; there were literally no surprises.” All the more remarkable when you consider that the cast included lions and tigers and bears, literally.

Exactly how seriously Crowe takes that commitment to preparation and rehearsal became clear when he cast Ashton Kutcher in Elizabethtown. Kutcher was then still part of That 70’s Show, and Crowe told him he had to set aside a few weeks to focus only on the film. But sources involved with the project say Kutcher didn’t heed Crowe’s words. Although he promised he would deliver when the cameras were rolling, Crowe lost faith. “The thing about Cameron is, he never gets angry,” says one involved in the production. He simply dropped Kutcher and, despite Paramount’s resistance, cast Bloom.

“I’ll spend months working with an actor, and I think I spent four months with Ashton,” Crowe says. “At a certain point, it’s like, ‘This is not meant to be.’ ” And though the film didn’t succeed with Bloom, Crowe says, “It felt like a noble crusade.”

Given actors and crew who are committed and prepared, it’s hard to imagine any director who could create a more generous and inclusive environment. “He has a strong vision, but he has a sense of collaboration that is embracing of other people,” says producer Wagner. “He likes to listen to people’s thoughts. It’s a special gift, really, that he has.”

Says Damon: “Everybody’s respected, and their work is respected. When you’re working with a benevolent dictator who wants to hear your opinion and the opinion of the entire crew, automatically you have this electric environment. Everyone comes to work with their ideas.”

Johansson felt it, too. “Cameron doesn’t just direct his actors, he conducts them,” she says in an e-mail from Scotland, where she’s filming Under the Skin with director Jonathan Glazer (Sexy Beast). “On any given take, he might be playing a song and throwing out impromptu dialogue, all the while motioning enthusiastically by the monitor. You can actually hear him chuckling and gasping from behind the video screen during each take. … He creates his own little world and invites everyone to live there for the run of production. Nothing is too over-the-top or too subtle to take a shot at. He’s willing to try everything once on the chance he might steal one precious moment.”

Says Crowe of the filmmaking process: “It’s gossamer. The best stuff is invisible. There’s no formula. You have to cross your fingers and leap.”

♦♦♦♦♦

Music weaves throughout Crowe’s life and movies. Singles, which followed friends in their 20s in Seattle, featured a song from Nirvana before the band got big. The track had to be dropped because by the time the film was done because the song had become too expensive to license. (“Kurt and Courtney snuck into the premiere at Grauman’s and watched the movie anyway,” Crowe says.) He also brought in pre-famous members of Pearl Jam to portray Matt Dillon’s band in the film.

Crowe keeps current: He thinks this is “one of the greatest times for music in decades. I’m talking about bands like the Civil Wars, Frightened Rabbit, the Belle Brigade, Dawes, Avey Tare, Sigur Ros, Radiohead, and Thom Yorke’s latest electronic phase.” Bob Dylan is Crowe’s favorite DJ; his “Theme Time Radio Hour” is “the best thing on satellite radio. There are 100 episodes, and each one is a classic. I listen incessantly.”

For We Bought a Zoo, Crowe got Jonsi of Sigur Ros to create a soundtrack. “He is very private, very picky about the projects he does, so we’re honored he did this score,” Crowe says. “The soundtrack — a first for us — is pure score, with two new songs, a 52-minute soundscape that is a complete musical journey, meant to be listened to from beginning to end. It ends with the movie’s end-title track, which Jonsi asked me to help write lyrics for. It was a surreal experience after only writing tongue-in-cheek songs for fake movie bands in our movies.” (The song is called “Gathering Stories.”)

Damon says Crowe played music on the set of We Bought a Zoo, which was enormously helpful to him in preparing to play emotionally charged scenes. “It was a technique I’ve never seen before,” Damon says. Sometimes the music overlapped with dialogue and lines had to be looped later, but in other cases, Crowe just played a part of a song before the scene was shot. It particularly illuminated a scene in which Damon is looking a photographs of his deceased wife.

“Music changes your mood and can bring you places that a lot of analysis and talking can’t,” Damon says.

Fox executive Watts says she saw that when she visited the set. “He was directing Scarlett and Matt in this one scene, and there was this moment he was trying to get. I was thinking, ‘I don’t know if he’s going to get it.’ And he plays a piece of music right before the next take — a piece of a particular song — and they started the scene, and there it is. He’s a national treasure, Mr. Cameron Crowe.”

For Crowe, the tactic produced the performance that he had to have. “What Matt does in the movie is that rarest of things: comedy and drama and real emotion,” he says. “The list of people who can do that is the shortest list in acting, and it’s the easiest thing to miss because he makes it look effortless. But it’s not. It’s the toughest. And for me, it makes the movie.”

Now that he’s gotten back in the chair on We Bought a Zoo with such happy results, Crowe says he’s eager to direct again. Not that he has any shortage of other projects. He’s still doing journalism and has recently done an interview with Neil Young that is scheduled to run in Rolling Stone next year. He’s also working on a compilation of his reporting on rock. “It’s calledHamburgers for the Apocalypse and includes new interviews with the artists I profiled in the day, from Zeppelin to Bowie to Joni Mitchell,” he says.

Crowe, who lives in Pacific Palisades, is also spending time with his sons, sharing custody with his former wife. “We go to the Pacific Dining Car in Santa Monica and have steaks and talk about girls,” he says. “I get most of my pointers from them these days. … We are fishing nuts and go sportfishing whenever we have time on the weekend. They’re great fishermen, and we all fish together and then eat all we catch in a big fish cook-off, usually while watching Food Network.” (Crowe’s other cable passion: Chris Matthews.)

But Crowe says he has scripts that he wrote in the past few years and hopes one of them will turn into his next directing gig. (He’s just sent out a spec script which he says is Preston Sturges-influenced.)

Although some in the industry observe that the business has changed since the days when studios were willing and able to lay wagers on the type of original material that has flowed from Crowe’s pen, he believes that the audience is waiting for just such films.

“Character comedy-drama is really hard to get made right now, and I think that’s a statement that feeds on itself,” Crowe says. “But it’s not necessarily true. It’s the nourishing thing that people crave. … People are going to go where they get characters that they remember. I don’t think people are ever going to a place where they’re like, ‘I’m over stories about character and love.’ ”

Crowe recalls a recent conversation his mother, Alice. “I can’t help but write about love,” he told her.

“What else is there?” she replied.

♦♦♦♦♦

Crowe’s Five Favorite Films

- Quadrophenia (1979)

- Local Hero (1983)

- Stolen Kisses (1968)

- The Rules of the Game (1939)

- The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

♦♦♦♦♦

MIX FOR MATT: No director knows music like Cameron Crowe. To woo Damon to do We Bought a Zoo, Crowe burned a CD for him. “Even if it’s not music that ends up in the movie, it’s the feeling that counts,” Damon says. Crowe played music on the set, too. By then, “Matt was emotionally DJ’ing and asking for songs.”

- Save It for Later … Pete Townshend

- I’m Open (Live) … Eddie Vedder

- War of Man (Live) … Neil Young

- Soul Boy … The Blue Nile

- Mohammed’s Radio … Jackson Browne

- Sanganichi … Shugo Tokumaru

- Airline to Heaven … Wilco

- Buckets of Rain … Bob Dylan

- The Heart of the Matter (Live) … Don Henley

- I Will Be There When You Die … My Morning Jacket

- Ain’t No Sunshine … Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers

- Child of the Moon … Rolling Stones

- If I Am a Stranger … Ryan Adams

- Concrete Sky … Beth Orton

- Helpless (Live) … Neil Young

- Don’t Be Shy (no piano) … Cat Stevens

- Nerstrand Woods … Mark Olson And The Creekdippers

♦♦♦♦♦

Why It’s So Hard to Find a Copy of Fast Times at Ridgemont High

The first time Cameron Crowe based a movie on a true story was nearly 30 years ago, when he wrote a screenplay from his first book, Fast Times at Ridgemont High: A True Story. The Amy Heckerling-directed film became a sleeper hit and a cult classic. At 22, Crowe had spent a year as a senior at Clairemont High School in suburban San Diego, chronicling the experiences of his “classmates.” Typical of Crowe, the book played both funny and sweet. But if you want to read that book, be prepared to open your wallet: Fast Times has been out of print since the early ’80s, and copies can be found on eBay and other sites at prices ranging from $125 to $345. And Crowe tells THR he likes it that way:

Why hasn’t Fast Times been republished?

It’s the one thing that I still have the rights to, and I like that there’s one thing that’s not readily available. I like knowing that if you really want it, you can find it, but nobody’s pushing it in your face. I have been approached about republishing, but I haven’t done it. I like it too much as a kind of bootleg.

Are you surprised about the prices?

I like those prices.

How do you feel about the book now?

I love the book. It’s one of my favorite things that I’ve ever written. The book opens the door where all the stuff I learned as a journalist can be applied to a non-celebrity and it’s just as interesting. You can interview a kid sitting in his room, and it’s more interesting than Rod Stewart. It very much opened a door to being a screenwriter because it let you know that it was a level playing field, story-wise.

Courtesy of the Hollywood Reporter – Kim Masters – November 20, 2011